Louise Glück

Biographical

Iwas born April 22, 1943 in New York City, where my parents were then living. I was their second child, but the first to survive. Three years later, after my sister was born, we moved to Woodmere, Long Island, a prosperous Jewish suburb on the south shore, known, like Great Neck on the north shore, for its excellent schools. These were, as far as I could judge, communities of displaced New Yorkers, mainly second and third generation. There was little sense, in such places, of Europe; certainly, there was very little sense of Hungary or Russia in my house. No language was spoken other than English, aside from my mother’s Wellesley French major French in ceremonious bursts and, less frequently, Japanese phrases she acquired when she and my father lived in Japan. My father was a businessman and a dreamer; his dreams took the form of inventions. He had, I was told, more than a hundred patents at his death. Together with his brother-in-law, he founded X-Acto, a company that adapted Japanese surgical instruments (my father’s area of expertise) to a knife meant for office and domestic use – also for the use of artists and architects. Much later, my sister was robbed with one outside a New York City bank. My mother was a housewife and celebrated cook, well-educated but without any particular sense of vocation. Nevertheless, she had the temperament and stamina and force of an empire builder.

I read very early. I read the stories that were read to me even earlier, the Greek myths, the Oz books. My father’s bedtime story for his daughters was the story of Joan of Arc, with the burning deleted. He also taught us to write books. We made up stories, which he transcribed for us on squares of paper that were folded to make pages, a certain number of words on each, leaving room for us to draw pictures. Somewhat later, but not much later, I found an anthology of poetry. Reading Blake and Shakespeare, I felt intensely that these were the people I wanted to be talking to. I wanted to be what they were. Later, there were music lessons, ballet lessons, art lessons.

There was a sense in the house that art was a noble calling. There was also a sense of the unlimited power of women (not yet actually affirmed in the world, but our household was, in its way, prophetic). Both my parents were born into matriarchies. My father’s family, new immigrants, consisted of five sisters and no brothers. The sisters were, many of them, actively political, radical for the time. My mother’s family had been American for several generations; my maternal aunts and my grandparents were bourgeois, the three sisters overshadowing their somewhat thwarted brother. I grew up with my cousins, two girls in each family; each family, each duo of daughters, had its own special characteristics. My mother, as the eldest daughter, tended to be lordly. Though she privately criticized us in the manner of the perfectionist ballet master, publicly she boasted, a fact unknown to me, but alienating to the cousins.

The summer I was seven and my sister was four and a half, we went to Paris. We lived there the whole of the summer, but for a week or so in Gstaad, where I had goats’ milk every morning, a strange food which I hated but pretended to like, resulting in larger and larger glasses. In Paris, we spent some afternoons sitting for our portraits in green square-necked dresses, but for the most part, we were at the convent school, theoretically learning French.

My sister and I were being raised according to the principles of a particular class at a particular time; parents protected their children from knowledge that might trouble their light-hearted and merry childhoods. I was never light-hearted and merry; rather, anxious and twitchy. Maybe it was thought that with enough protection I might still become light-hearted and merry, or maybe my parents were reluctant to admit that their older daughter was a very tense child. Or maybe they had, that summer, more pressing concerns.

The nuns had assured my mother they would not proselytize, but obviously the nuns obeyed a higher authority than my mother. And, strictly speaking, introducing young Jewish children to Jesus was not proselytizing. We were, one afternoon, taken to the chapel, just the two of us, with the kindly nun who spoke English (since I had steadfastly refused to learn French, and my sister had followed my example.) This is Jesus, the nun said, he loves little children. Now you must kneel and say a prayer. Young as we were, we had mastered two imperatives. We knew to obey the adult in charge, and we knew Jews did not bow down before statues. So it was clear to me in that moment (as it was to my sister) that there was no possibility in this situation of not doing wrong. I did not bow down. But I did not obey. I judged the more serious sin to be the moral sin, not the social sin.

Decades later, when I was in my late thirties, my sister called me. She had just learned at dinner with my parents that a few years before our trip to Paris, my father’s second oldest sister, a woman of intellectual distinction and modest political renown, had not died of heart failure, as we were told, but had in fact killed herself, leaving behind two small children. For several years afterward my father had apparently been sinking perilously into depression. Finally my mother insisted he consult a psychiatrist who recommended analysis; this my father refused. He told the doctor he was going to take his family to Paris and come back whole.

School was my world. I loved school. Home was complicated, playing with other children was complicated. School was easy. The rules were clear. And my teachers loved me, as I passionately loved them. Starting in grade school. They were emissaries from the world of Blake and Shakespeare. It seemed wonderful to know so clearly what was wanted. Obedience, in this context, was effortless, natural. I saw it as somehow collaborative, part of my dialogue with my teachers, and by extension with the great artists I hoped to follow. This was true in grade school and more intensely true in high school, especially with English teachers, and my Latin teacher. I did it all well. What I did not do well was the social world.

There was one place, during the difficult period of my adolescence, where I was not ostracized. Starting when I was about thirteen, I spent most summers in music camps. I was not a particularly gifted musician. I majored, as it was called, in drama. And though I was not a particularly gifted actress, I was a quick study; I could be counted on to know my lines. But in that summer world of driven and ambitious students, I was at ease; real friendships were made. I loved best a camp called Deerwood (which collapsed when its director died, revealing immense debt) on Saranac Lake, which became for me the model of all things great and true. Evenings, the camp’s most gifted trumpet player would play taps by the lake. Around us, the serene protective isolating mountains.

Woodmere was a different matter, darker and darker. I spent my afternoons in the public library, concealing the absence of a social life from my mother. My ambitions remained intense and steady. By the age of sixteen, I had finished my first book, or what I thought of as my first book, and sent it along to publishers with no timidity or sense of irony. It ended up in a box, but lines I wrote at thirteen and fifteen showed up much later, reconstituted slightly, in poems that survived. I read constantly. Oddly, I knew nothing of what was being written in that period, or even in the period slightly earlier. I read Keats and Dickinson, obsessively haunted by syntax. I read novels too, mainly British. I discovered Yeats. And I became, first inconspicuously, then dangerously, anorexic.

In the middle of my senior year of high school, after I had applied early to, and been admitted to, the first rank college of my choice, I was taken out of high school. I had begun psychoanalysis a month or so earlier; in its slow way, ultimately it saved me from the narrower and narrower worlds I constructed for myself, from the arid brevities of my poems at that time. Initially, of course, I was terrified. But the seven years I spent in analysis radically changed the course of my life. They made my life possible, really.

After a year or so, when I was physically strong enough, and liberated, to some degree, from the imprisoning rituals I invented to compensate for the loss of that sense of control anorexia provided, I began taking workshops in poetry at Columbia University’s School of General Studies. Two years with Leonie Adams, and many more than two with Stanley Kunitz, in whose class I wrote the poems that became my first book.

It was also during this period, when I was nineteen or twenty, that I had my first grand mal seizure, on Fifth Avenue, opposite the Metropolitan Museum of Art, on a beautiful October day. I had been walking, I suppose to the subway, after an appointment with my analyst. Epilepsy was not immediately diagnosed (a single seizure was not felt to be sufficient evidence); when it was, it took some time to fix on a medication, and on the correct dose.

I was fortunate in my teachers. Kunitz in particular did not condescend to his students; he seemed prepared to believe great work could be done in that classroom. I believed the same, or I hoped the same, but his endorsement of high ambition was fortifying.

Firstborn, begun when I was eighteen and finished when I was twenty-three, was rejected twenty-eight times and finally accepted by New American Library, which intended to make it the first book in its new poetry series. The series never happened. But I did see stacks of my books in New York bookstores for a while, looking oddly fraudulent amid the legitimate books.

And then the gift, the talent, the facility died. I stayed in New York for a few years. I doggedly persisted as I thought writers needed to do. I sat at my desk, surrounded by blank paper. The longer this went on the more rigorously I banished from my life every possible diversion or distraction.

I have written about this period elsewhere. At the end of something like two and a half years I had to face the fact that it was not given me to make art. I was twenty-seven, living, by then, in Provincetown, with one of a series of romantic attachments, following my very brief first marriage. Provincetown: a bad place to be confronting this despair.

In the spring of my last year there, I was invited to participate in a colloquium at Goddard College; other guests would include John Berryman, whom I revered. It was a moment, in the U.S., of a new curiosity about women poets, and my already repudiated first book was having, it seemed, an afterlife.

I took a bus, a series of buses, to Plainfield, Vermont. When I got off the bus, the clouds shifted a little. I had a profound sense that I was meant to live in this remote, rural village, in one of the coldest parts of the country, though I had thought of myself as a person who thrived in cities and needed warmth. But I realized, gradually, that I recognized the landscape; Plainfield was like Saranac, the calm mountains surrounding the protected valley. Ponds and rivers replaced the lake. I had found my way back, it seemed.

The festival lasted four days. At one of the parties after one of the readings, all of us enjoying ourselves immensely, one of my soon to be best friends urged me to come back to teach there. In my extreme naivete, I had no notion of the fact that drunken English teachers are not empowered to offer jobs to strangers. For me, it was an epiphany. If there was one thing I was sure poets shouldn’t do, it was teach. A waste of those vital resources we should channel into our work. In my previous life as a young poet, I’d have said no. But in my new life as a wandering desolate girl, I said yes. Why not, is what I thought. Then the four days were over, and I went back to Provincetown. This was, I imagine, May. But an actual job, abbreviated, provisional, materialized at the end of the summer, four days before the start of school. So I moved my never unpacked boxes, which had followed me from New York to Provincetown, to a rooming house where my new friends, now colleagues, had found me a room, a cross between a New England farmhouse and a bordello. And my spirit rested, if elation can also be experienced as rest.

Plainfield was indeed the place I believed it to be. But teaching was a miracle. The envy I thought I’d feel toward talented younger writers, I did not feel. Nor did I viciously and jealously offer them bad advice to suppress their gifts. What I felt was the old avidity to transform the inert poem with its single luminous line into something wholly memorable and distinctive. My mind was being used again. And then, amazingly, I started to write my own work, poems utterly different from the rigid performances of my first book.

I had noticed, as I labored over the structure of that first book, that I seemed to have forgotten how to write sentences. So I set myself a task: poems that were, ideally, built out of a single sentence, but in any case, built of complex sentences with long suspended clauses draped over several lines. I think my silence, my long sleep, was teaching me a new sound able to enact that assignment.

The year that followed, my first year in Vermont, was extraordinary. I was elated to be writing again, and excited by this new, much more original work. And I loved teaching. Moreover, it seemed probable teaching was something I could do, unlike my own writing, regardless of internal factors. And my heart was (yet again) engaged. I joined a workshop of local poets, stern, discriminating readers, and some of them, electrifying writers.

I discovered that I could teach one term elsewhere, when Goddard dried up, and make enough to live in Vermont the rest of the year. I moved out of the rooming house into a series of charming dilapidated apartments. At some point, when my second book was nearly done, I went with one of my best friends to see the famous local psychic.

She had an encouraging report. Great success, she said; she saw five books in my future. A magnificent fortune; I was writing very slowly; at one book per decade, five books would take me well into old age, at which point I could probably die serenely triumphant. This prediction came to have another message sometime later.

Meanwhile, I was pregnant. Unintentionally, as had happened before. But this time, I had a second book; I had, also, a profession. And I had a home. The baby’s father was very young. That he balked suited me; in Plainfield, Vermont in the early seventies, people were making these choices.

Noah was born in June; I was just thirty. Looking at him, I felt immediately the rashness of my decision; who was I to say a child needed only one parent? Especially if that parent was me, someone deeply preoccupied and, in most matters, impatient.

When I thought about having a child, I was also aware that my poems had begun to seem to me repetitious. I wrote love poems, and naturally I also wrote poems of loss. It was clear to me that unless my life contained more experience than my native cautiousness would naturally put in my path, I would be a lyric writer of no real range. I found myself a mother, inextricably involved with another person, at a time when I was, for various reasons, more open to bold experiment, to risk.

But the poor baby! At the typewriter, while he slept, I set myself a task. In this case, to eschew the moody nouns and luminous adjectives that gave my second book its otherworldly detachment. When Noah was just shy of two, I met the man I would marry.

Years passed. We bought a house in the country; the house burned down. We bought another house, back in the village. Books were written, a few prizes won. We made a small garden, then a bigger garden. I had a new task: to use contractions and questions. And I realized that contractions and questions specify the human voice; a quotidian world began to appear. The Delphic was gone; the definite article yielded to the indefinite article. And then there was a deep fissure with Stanley Kunitz over Ararat. Unpublishable, he said. This was my fifth book, my last according to the clairvoyant, a book from which all figurative language had been banished. Stanley was not pleased to be disagreed with.

Long periods of silence. After the disputed Ararat, a brutal punitive blankness. I cooked. Two years. I read garden catalogs and listened to Don Giovanni. The terrible judgment of the clairvoyant merged with my teacher’s dismissal, echoed through mainly scornful reviews. And then, The Wild Iris, written in a summer, putting to rest the prophecy.

I had the good fortune, if indeed it is good fortune, to write poems that accorded with the tastes of the period. So there were prizes. The Pulitzer. Later the Bollingen. Later still, the Stevens Prize, the gold medal from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Later still, the National Book Award, and from President Obama, the National Humanities Medal. And I learned that though the hope was that the book so anointed was alive, it was clear the author was not. The author was a prior self, not the person receiving the statue. So the prize, the book, became taunts: Look what you could do once. What can you do now?

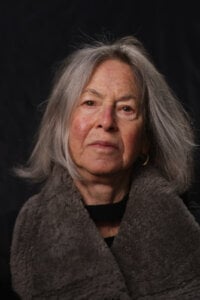

Figure 5.

I taught all over America, in the proliferating MFA programs that ignored my lack of formal education. North Carolina, Virginia, Cincinnati, Iowa City, New York. The multiple California Campuses: Berkeley, Davis, Irvine, UCLA. And then a term teaching inspired undergraduates at Williams College, a job that could actually incorporate itself into my life. With these undergraduates, I felt a thrill that never abated. And the temporary job became a renewable, and renewed, position.

Twenty years. The marriage flourished, the marriage ended. I moved to Cambridge — utterly unlikely, I would have said. I changed teaching positions. I left behind Williams, my other world, for the equally brilliant Yale undergraduates. A more manageable commute, a more compact work week. Amazingly, the intensity sustained itself.

What did not change were the terrible extended periods of silence, the anxiety. And, periodically, the elation of discovery, the strange embarking, the adventure that writing is, each poem a journey into unknown territory.

I continued to rely on music. Beginning with The Wild Iris, it seemed each book had a score; the music usually announced itself before the poems. Purcell, Mahler, Brahms. Sam Cooke. I continued to try to push myself grammatically, each such change elaborating itself into new material. I thought finally to write poems about making art, though in the main I detested poems about art. But it was, after all, the project on which I had spent my life.

A decade or so ago, my books began to be translated into other languages; each such book made me strangely happy. There was something elemental in these poems being attached to my name, though I couldn’t read them. Like a child’s dream of seeing her name on a book, a dream I had all my life. And there was even a prize from a country not my own. The Tranströmer Prize, named for a writer from whom I learned profoundly. And then the Nobel Prize.

I changed my wall calendar, Cats in the Sun, for a calendar with photographs of Sweden.

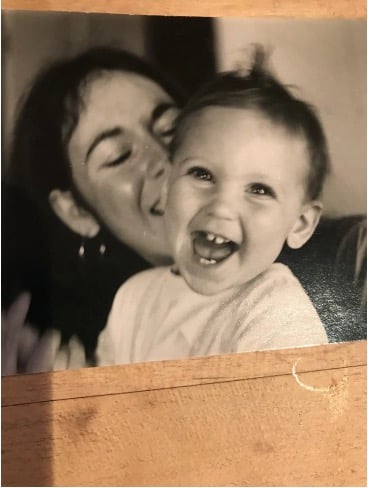

Figure 6.

Always domestic life soothed me and teaching excited me, unnerved me. Always I liked the day to end among people.

Except when it is insanely easy, writing remains elusive. Always I am someone longing to be a poet, to make something never heard before, to be taken out of myself. That it happened at all is a wonder.

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 2021

Louise Glück died on 13 October 2023.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.