Annie Ernaux

Biographical

Iwas born in 1940 in Lillebonne, a small working-class town twenty-five kilometres from Le Havre. I was an only child and my parents, Alphonse and Blanche Duchesne, ran a small café-grocery in the spinning mill district. They had lost a little girl of six before I was born. My earliest memories are inseparable from the war and the bombing raids that ravaged Normandy in 1944.

After the war, my parents returned to Yvetot, the town between Le Havre and Rouen where they both were born and had worked in a factory. I lived there for my entire childhood, until age eighteen, moving back and forth between two socially opposite milieux – my parents’ business, on the outskirts of Yvetot, and the private Catholic boarding school where they had enrolled me, in the town centre.

Very early I showed an aptitude for study and a love of reading, which my mother encouraged. Of poor health, I was spoiled with books and nice clothes acquired at the cost of many sacrifices on the part of my parents.

At eighteen, after completing the first part of the baccalauréat, I left for secondary school in Rouen to do the second part, in philosophy. So began two years of deep emotional suffering, with bouts of bulimia followed by periods of anorexia. Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex was a revelation, opening my eyes to “a world made by men and for men.”

At nineteen, with no plans or desires, I entered the École Normale for schoolteachers in Rouen as a boarding student. Unable to bear the confinement and the spirit of the place, I left in the middle of the school year. That is how I ended up in Finchley, on the outskirts of London, cleaning house all morning but free for the rest of the day. I read a great deal – contemporary French literature, of which there was a well-stocked section in the Finchley lending library. From this emptiness, my desire to write a novel was born, interrupted when I returned to France to enter the Faculty of Arts at the University of Rouen. As a scholarship student, I felt obliged for the sake of my parents to pass my exams and find a profession.

In October 1962, I revised the novel I had started to write in England. Completed in four months, it was rejected by two or three publishers. In June 1963, I obtained a degree in modern literature. At that time, I saw a future for myself as a woman who writes while earning her living as a teacher. The following summer, I met Philippe Ernaux, a political science student in Bordeaux. I became pregnant, and, intent on finishing my studies at a time when abortion was prohibited in France, I turned to a backstreet abortionist, called a faiseuse d’anges in French.

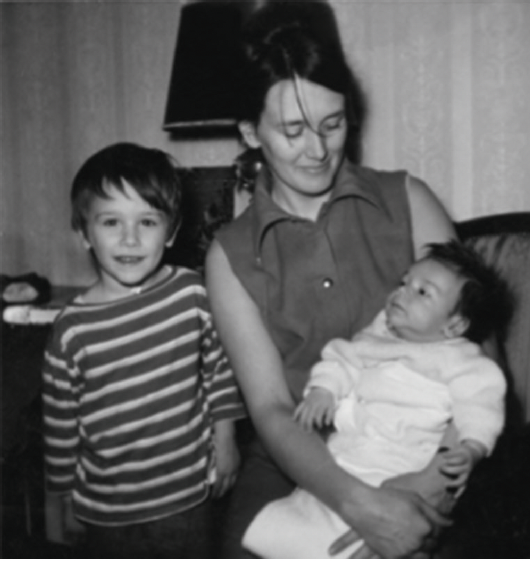

I married Philippe Ernaux in 1964, and our first child, Éric, was born on December 25th. We were still students and lived in Bordeaux in difficult material circumstances. I failed the agrégation. My husband graduated in political science.

In 1965, we left for Annecy, a tourist town in the Alps, where my husband had taken up an administrative post. At the end of June 1967, after passing the competitive examination to become a teacher of literature, I went to Yvetot to see my parents. The next morning, my father suffered a heart attack and died three days later. I knew this was the most violent and inexpressible break in my life that I would ever experience. In September I was assigned a teaching position in a secondary school forty kilometres from home.

I was only remotely involved in the events of May 1968 that caused such great upheaval in France, as I was expecting my second child, David, born in October of that year. One year later, I was appointed to a teaching post in Annecy. My mother came to live with us and looked after the children. This enabled me to study, once again, for the agrégation in literature, which I obtained in 1971, and, in the spring of 1972, to start work on the book I had been thinking about for four years. I wrote in secret, in the afternoons when I had no classes, and sent it by post to three publishers. It was published as Cleaned Out, by Gallimard, in April 1974. I was thirty-three years old.

In 1975, we moved to Cergy-Pontoise, a new town, still under construction, and during the summer of 1976, I wrote a second book, Do What They Say or Else. I had little time to write because of teaching, the children and domestic chores. This situation, common for women, of assuming the double burden of family and professional life, inspired the book A Frozen Woman, published in 1981.

This book foreshadowed the change I would make in my life, in my early forties. I separated from my husband and lived with my sons. It was then that I found a form for the book about my father. Entitled A Man’s Place, it marks a definitive break with the novelistic genre. In spite of its success, I chose to keep my teaching job so that I would never have to depend on commercial success.

After that, my books arrived at irregular intervals, A Woman’s Story, about my mother, who had Alzheimer’s disease and died in 1986, Simple Passion, Exteriors, Shame, Happening, and were more numerous after 2000, when I retired from teaching: The Possession, L’écriture comme un couteau, The Use of Photography. I was able to successfully complete the writing of The Years, a collective historical and social autobiography.

Since 1977, I have lived and written in the same house on the heights of Cergy-Pontoise.

Translated by Alison L. Strayer

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.