“It helped me to write on”

Every year, the new Nobel Prize laureates are asked to donate objects with special meanings, to the Nobel Prize Museum in Stockholm. Here the 2024 Nobel Prize laureates tell the stories behind their chosen objects.

“It helped me to write on”

While she was writing the book I Do Not Bid Farewell, this tea cup was part of Han Kang‘s daily habits. On the sheet of paper, she describes her work routine. After getting up at 05:30 am and going for a walk, she would drink a cup of tea. (She drank black tea although the cup is intended for green tea.) When she stared at the vortex that formed in the cup, it became her universe.

“I didn’t need to take too much caffeine, since the teacup is so small. It was like very warm medicine for me, which helped me to write on,” said Han Kang.

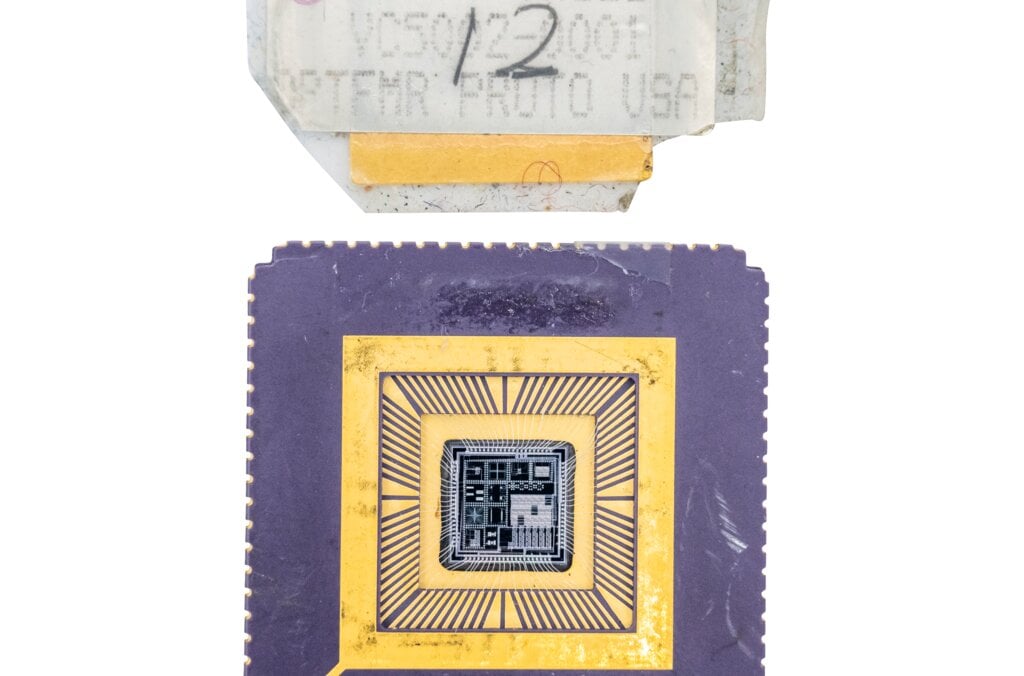

Microchip with importance for machine learning

This microchip contains an early version of a Boltzmann machine, which Geoffrey Hinton plays a decisive part in developing. The Boltzmann machine is vital to machine learning with neural networks, and Hinton is one of the leading figures in artificial intelligence (AI).

The microchip, made by Joshua Alspector in 1987, demonstrates that Boltzmann machines can be placed on specially-constructed chips. The Boltzmann machine on this chip is tiny; it is a network with six nodes, and it has a rather limited field of use. As a demonstration of a principle, however, the microchip showed the way toward further progress in machine learning and AI.

A challenge prize

This paper crown was a kind of challenge prize in John Jumper‘s research team, which explores the structure of protein molecules. The research team was called “the Origami team” at an early stage, since they saw links between how long protein molecules are folded and the art of folding paper into figures. Whenever someone in the group made progress, they got to wear the paper crown as a reward, and kept it until they passed it on to the next person who did something worth rewarding.

Jumper and his colleagues don’t usually work with paper models but with computers and artificial intelligence. They developed AlphaFold2, an algorithm that can predict the three-dimensional structure of any imaginable protein.

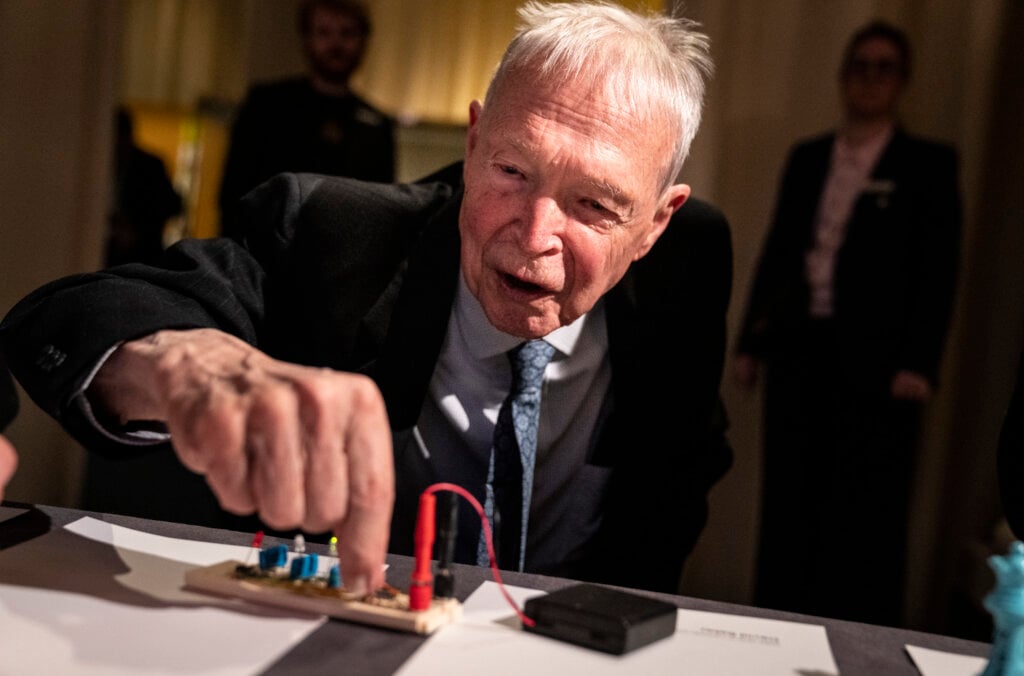

Practical building as essential to understanding

This electronic circuit was built by John Hopfield in the early 2000s in connection with a course he taught at Princeton University. Hopfield had made significant contributions to machine learning in the 1980s, with neural networks, which are crucial in artificial intelligence.

Hopfield considers practical building to be essential to understanding.

“I designed a lab course in electronics for neural networks. My strong feeling was that we obtain a deep understanding of how a NN behaves by building and exploring the activity dynamics. Begin with small circuits, each student has her/his own assembled by hand from a pile of electronic components. This is my own demonstration-assembly of the 4th week project,” said John Hopfield.

The circuit consists partly of diodes that turn on and off when different parts of it interact.

Four objects related to gaming

As a four-year-old, Demis Hassabis devoted a lot of his time to chess. His interest in chess eventually led to an interest in computers that could play chess. Hassabis devoted himself increasingly to computers and artificial intelligence (AI). He participated in creating the AI model AlphaFold, which can predict the three-dimensional structure of protein molecules.

Demis Hassabis also donated chess pieces, that symbolise his passion for chess. They are two spare queens for a game designed by the artist Thierry Noir. He is famous as one of the first artists to begin making graffiti art on the Berlin Wall in the 1980s. The board design also features a pattern suggestive of electronic circuits.

Another of Hassabis’ donations is the book Game Changer by Matthew Sadler and Natasha Regan. The book is about the computer program AlphaZero, developed by Demis Hassabis and his colleagues at DeepMind. The introduction is written by Hassabis and the foreword by Garry Kasparov, who in 1997 was the first world champion chess player to lose against a computer.

A cube concludes Demis Hassabis’ object donations. For Hassabis and his colleagues at DeepMind, the cube is a symbol for how the solution to one problem can lead to the solution of many others. One of the cube sides shows move 37, the decisive move in a game of Go where the master Lee Sedol lost in 2016 against the AlphaGo program that had been developed by DeepMind. This was the first time a top-level master lost against a computer, and the event is a milestone in the development of artificial intelligence. AlphaGo was followed by AlphaZero, which plays chess, Shogi and Go. AlphaFold, which was developed later, can predict the thee-dimensional structure of protein molecules.

A broken ski pole representing overcoming obstacles

This is one of many ski poles David Baker has broken over the years. Skiing and hiking are two recreational activities he values highly. He also sees a symbolic meaning in the broken pole. His pole was broken, but he still needed to get down from the mountain. The same applies to other areas in life, including research; when something does not go as planned, it is necessary to carry on and overcome obstacles.

David Baker also donated a pair of glasses.

“I had an eye injury several years ago that made it impossible for me to look at computer screens; I was in despair about how to work for a month, when I discovered that the orange glasses solved the problem. I wear them when I give presentations, and so they have almost become part of my persona—I often get as much positive feedback about the glasses as the content of the talks!” said David Baker.

Bakers’s third item is a model of proteins. The large, red part of the model is the spike protein from the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes Covid-19. The blue and green parts represent synthetic proteins developed by David Baker and his team. These proteins bind tightly to the spike protein and have proven to prevent the virus from infecting animals. The proteins have not yet undergone the required testing for use on humans.

A memory of a mother

This paperweight is one of very few mementos that Daron Acemoglu has of his mother Irma, who meant a lot to him. Daron Acemoglu grew up in Istanbul, in a family of Armenian origin. His mother was a teacher and the headmistress of the Armenian school that her son attended, and she encouraged him to study. Irma Acemoglu died in 1991.

A passport carrying family history

This passport belonged to Simon Johnson‘s grandfather Cyril John Dadswell who died when Johnson was only two weeks old. But Dadswell was nevertheless important to Johnson, as the first academic in their family. Dadswell was a metallurgist and worked for the steel industry in Sheffield. The passport was issued on 14 May 1942, during the Second World War, and it also reveals that Dadswell immediately obtained a visa for the USA. The purpose of his trip to the USA was to provide expertise on steel suitable for tanks. Dadswell’s activities are related to one of Simon Johnson’s areas of research: how technology is transferred between different countries and fields.

Simon Johnson donated the passport to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2024.

“I never knew him but I knew of him and his stories and his achievements were always with me. He was the first person ever in my family to graduate from college and I was the second,” said Simon Johnson.

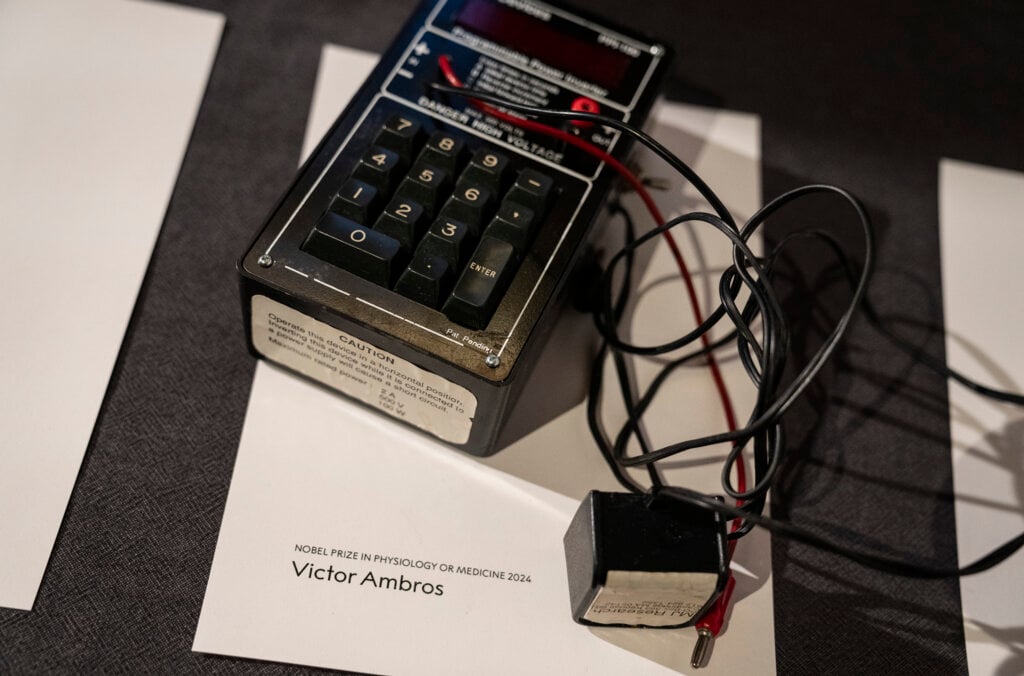

An instrument representing new technology

This instrument was used in the late 1980s in Victor Ambros‘s research on microRNA, which is crucial to how different genes impact on different cells.

The instrument is a fractionation device for a type of electrophoresis used to separate DNA fragments of different sizes. Ambros used it to produce large pieces of purified DNA. This was a crucial step in the examinations of the lin-4 gene and its impact on microRNA.

The instrument was the first to be developed by the company MJ Devices, founded by the brothers Michael and John Finney. Incidentally, Michael Finney was also a doctoral student in the future Nobel Prize laureate Robert Horvitz‘s laboratory.

“This object represents a specific time in the history of molecular biology and a time in our careers, when new technology came out that enabled us to do something that we wouldn’t otherwise do,” said Victor Ambros.

Passion for African history and culture

The mask and fly-whisks are from the Kuba people in the Democratic Republic of Congo. James A. Robinson is deeply interested in African history and culture and has devoted 12 years to studying the Kuba people in his research on social institutions. The mask is a “bwoom”, one of three primary masks used to narrate the history of the kingdom and retell a few key historic events. The fly-whisks, which are useful for whisking away flies, are also attributes used in this context.

James A. Robinson donated the mask and fly-whisks to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2024.

All objects were donated to the Nobel Prize Museum in 2024.

Discover more

Learn more about the 2024 Nobel Prizes and laureates here

Explore more objects from Nobel Prize laureates here

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.