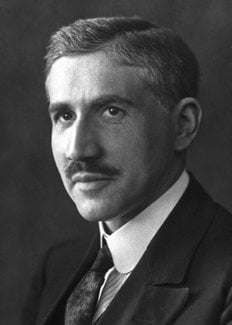

Otto Meyerhof

Biographical

Otto Fritz Meyerhof was born on April 12, 1884, in Hannover. He was the son of Felix Meyerhof, a merchant of that city and his wife Bettina May. Soon after his birth his family moved to Berlin, where he went to the Wilhelms Gymnasium (classical secondary school). Leaving school at the age of 14, he was attacked, at the age of 16, by kidney trouble and had to spend a long time in bed. During this period of enforced inactivity he was much influenced by his mother’s constant companionship. He read much, wrote poetry, and went through a period of much artistic and mental development. After he had matriculated, he studied medicine at Freiburg, Berlin, Strasbourg, and Heidelberg.

In 1909 he graduated in medicine with a thesis on a psychiatric subject and devoted himself for a time to psychology and philosophy, publishing a book entitled Beiträge zur psychologischen Theorie der Geistesstörungen (Contributions to the psychological theory of mental disturbances) and an essay on Goethes Methoden der Naturforschung (Goethe’s methods of scientific research). Under the influence of Otto Warburg, however, who was then at Heidelberg, he became more and more interested in cell physiology. After working for a short time on physical chemistry with Bredig at Heidelberg, Meyerhof spent some time in the laboratory of the Heidelberg Clinic and at the Zoological Station at Naples. In 1912 he went to Kiel, where he qualified in 1913, under Professor Bethe, as a university lecturer in physiology; and lectures which he delivered at Kiel, in England and the United States were published as The Chemical Dynamics of Living Matter. In 1915, when Professor Höber assumed the Directorship of the Institute of Physiology, Meyerhof was appointed Assistant. In 1918 he became Assistant Professor. In 1923 he was offered a Professorship of Biochemistry in the United States, but Germany was unwilling to lose him and in 1924 he was asked by the Kaiser Wilhelm Gesellschaft to join the group working at Berlin-Dahlem, which included C. Neuberg, F. Haber, M. Polyani, and H. Freundlich.

In 1929 he was asked to take charge of the newly founded Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research at Heidelberg. In 1938 conditions became too difficult for him and he decided to leave Germany. From 1938 to 1940 he was Director of Research at the Institut de Biologie physico-chimique at Paris, where he was helped financially by the Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation.

In June, 1940, however, when the Nazis invaded France, he had to flee from Paris. Driving with his family to Toulouse, he was befriended by the Medical Faculty there, but escape became essential and a tragic flight followed. Eventually, with the help of the Unitarian Service Committee, he reached Spain and ultimately, in October 1940, the United States, where the post of Research Professor of Physiological Chemistry had been created for him by the University of Pennsylvania and the Rockefeller Foundation.

Meyerhof’s own account of his earlier work states that he was occupied chiefly with oxidation mechanisms in cells and with extending methods of gas analysis through the calorimetric measurement of heat production. In this manner he studied the metabolism of sea-urchin eggs, blood corpuscles, and various bacteria and especially the respiratory processes of nitrifying bacteria.

He also studied the effects of narcotics and methylene blue on oxidation processes, and the respiration of killed cells. The physico-chemical analogy between oxygen respiration and alcoholic fermentation caused him to study both these processes in the same subject, namely, yeast extract. By this work he discovered a co-enzyme of respiration, which could be found in all the cells and tissues up till then investigated. At the same time he also found a co-enzyme of alcoholic fermentation. He also discovered the capacity of the SH-group to transfer oxygen; after Hopkins had isolated from cells the SH bodies concerned, Meyerhof showed that the unsaturated fatty acids in the cell are oxidized with the help of the sulphydryl group. After studying closer the respiration of muscle, Meyerhof investigated the energy changes in muscle.

Of Meyerhof’s many achievements, perhaps the most important is his proof that, in isolated but otherwise intact frog muscle, the lactic acid formed is reconverted to carbohydrate in the presence of oxygen, and his preparation of a KC1 extract of muscle which could carry out all the steps of glycolysis with added glycogen and hexose-diphosphate in the presence of hexokinase derived from yeast. In this system glucose was also glycolysed and this was the foundation of the Embden-Meyerhof theory of glycolysis. For his discovery of the fixed relationship between the consumption of oxygen and the metabolism of lactic acid in the muscle, Meyerhof was awarded, together with the English physiologist A.V. Hill, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for 1922.

The discovery of Otto Meyerhof and his students that some phosphorylated compounds are rich in energy led to a revolution, not only of our concepts of muscular contraction, but of the entire significance of cellular metabolism. A continuously increasing number of enzymatic reactions are becoming known in which the energy of adenosine triphosphate, the compound isolated by his associate Lohmann, provides the energy for endergonic synthesis reactions. The importance of this discovery for the understanding of cellular mechanisms is generally recognized and can hardly be overestimated.

In 1925 Meyerhof succeeded in extracting the glycolytic enzyme system from muscle, retracing a pathway which Buchner and Harden and Young had explored in yeast. This proved to be a decisive step for the analysis of glycolysis. Meyerhof and his associates were able to reconstruct in vitro the main steps of the complicated chain of reactions leading from glycogen to lactic acid. They verified some, and extended other, parts of the scheme proposed by Gustav Embden in 1932, shortly before his death.

Among other honours and distinctions, Meyerhof was a Foreign Member of the Harvey Society and of the Royal Society of London, and a Member of the National Academy of Sciences of the U.S.A.

As a man Meyerhof was a fine experimenter and a master of physiological chemistry. By temperament he was most interested in theory and interpretation and he had a remarkable gift of integrating a variety of phenomena. He spent much time daily at his desk and in stimulating discussions with his pupils and collaborators. His chief scientific work was accomplished while he was at Heidelberg, but he also produced much while he was in America; and in America also he showed that he had never relinquished his active interest in philosophy by presenting to the Goethe Biennial Celebration of the Rudolf Virchow Society in New York a profound and critical evaluation of Goethe’s scientific ideas. Throughout his life he retained a great love of art, literature, and poetry. His interest in painting was much stimulated by his wife Hedwig Schallenberg, herself a painter, whom he married in 1914. There were three children of this marriage.

In 1944 he suffered a heart attack; in 1951 another one which ended his life.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Otto Meyerhof died on October 6, 1951.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.