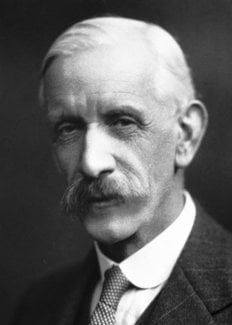

Sir Frederick Hopkins

Biographical

Frederick Gowland Hopkins was born on June 20, 1861, at Eastbourne, England. His father, a bookseller in Bishopsgate Street, London, was much interested in science, but he died when Gowland was an infant. For the next ten years Gowland lived with his mother at Eastbourne, showing as a child literary rather than scientific tastes, although, when his mother gave him a microscope, he studied life on the seashore. But he read much and wrote rhymes, and in later life speculated as to whether he might not have become, if he had been encouraged to do so, a classical scholar or a naturalist. Later in his life, however, his literary ability added much to all his scientific papers and addresses.

In 1871 his mother went to live at Enfield, and Hopkins went to the city of London School. He was a bright schoolboy in several subjects, and was given a first-class in chemistry in 1874. Later, as a result of an examination at the College of Preceptors he was given a prize for science, and, at the early age of 17, when he finally left school, he published a paper in The Entomologist on the bombardier beetle.

After working for six months as an insurance clerk, Hopkins was articled to a consulting chemist, and subsequently, after taking a course in chemistry at the Royal School of Mines, South Kensington, London, he went to University College, London, where he took the Associateship Examination of the Institute of Chemistry, and did so well that Sir Thomas Stevenson, Home Office Analyst and expert on poisoning, engaged him as his assistant. He was then 22 years old, and he took part in several important legal cases. He then decided to take his London B.Sc. degree and graduated in the shortest possible time. In 1888, when he was 28, he went as a medical student to Guy’s Hospital, London, and was immediately given the Sir William Gull Studentship there. He was awarded, during this period, a Gold Medal for Chemistry, and Honours in Materia Medica.

In 1894, when he was 32 years old, he graduated in medicine and taught for four years physiology and toxicology at Guy’s Hospital. For two years he was in charge of the Chemical Department of the Clinical Research Association. In 1896 he published, with H.W. Brook, work on the halogen derivatives of proteins, and in 1898, work with S. N. Pinkus on the crystallization of blood albumins. In 1898, when attending a meeting of the Physiological Society at Cambridge, he was invited by Sir Michael Foster to move to Cambridge to develop there the chemical aspects of physiology. Biochemistry was not, at that time, recognized as a separate branch of science and Hopkins accepted the appointment. Given a lectureship at a salary of £200 a year, he added to his income by supervising undergraduates and giving tutorials, doing also for a few years, after the death of Sir Thomas Stevenson, part-time work for the Home Office. Later he was appointed Fellow and Tutor at Emmanuel College, Cambridge.

In 1902 he was given a readership in biochemistry, and in 191O he became a Fellow of Trinity College, and an Honorary Fellow of Emmanuel College. In 1914 he was elected to the Chair of Biochemistry at Cambridge University. During all this time he had to be content with, at first, one small room in the Department of Physiology, and later with accommodation in the Balfour Laboratory; but in 1925 he was able to move his Department into the new Sir William Dunn Institute of Biochemistry which had been built to accommodate it.

Among his outstanding contributions to science was his discovery of a method for isolating tryptophan and for identifying its structure.

Subsequently he did the work which was to gain him in 1929, together with Christiaan Eijkman, who had demonstrated the association between beriberi and the consumption of decorticated rice, the Nobel Prize.

Later, Hopkins worked with Walter Fletcher on the metabolic changes occurring in muscular contractions and rigor mortis. Hopkins supplied exact methods of analysis, and devised a new colour reaction for lactic acid, and the pioneer work then done laid the foundations for the work of the Nobel Laureates, A.V. Hill and Otto Meyerhof, and also for that of many other later workers.

In 1921 he isolated a substance which he named glutathione, which is, he showed, widely distributed in the cells of plants and animals that are rapidly multiplying. Later he proved it to be the tripeptide of glutamic acid, glycine and cystein. He also discovered xanthine oxidase, a specific enzyme widely distributed in tissues and milk, which catalyzes the oxidation of the purine bases xanthine and hypoxanthine to uric acid. Hopkins thus returned to the uric acids of his earliest work, a method of determining uric acid in urine, which he first published in 1891.

Hopkins was knighted in 1925 and received the Order of Merit in 1935.

He was awarded the Royal Medal of the Royal Society of London in 1918, and its Copley Medal in 1926. From 1930 until 1935 he was President of the Royal Society, and found little time for research. During this period, however, he exerted great influence on his contemporaries.

In 1898 Hopkins married Jessie Anne Stevens. They had two daughters, one of whom Jacquetta Hawkes, is married to J. B. Priestley, the author.

Hopkins died in 1947, at the age of 86.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Sir Frederick Hopkins died on May 16, 1947.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.