Hugo Theorell

Article

Hugo Theorell, My Father

by Henning Theorell

This article was published on 24 February 2011.

Looking for source material 25 years after anybody’s death is never easy, but what follows reflects my best efforts to cast some light on the personal life of my father, Hugo Theorell (1903–1982). Hugo Theorell is perhaps best known for his pioneering career in enzyme research, and for being awarded the 1955 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for “his discoveries concerning the nature and mode of action of oxidation enzymes”. What is abundantly clear from both my recollections and my research is that my father was also a renaissance man; a man whose life was marked by overcoming a lifelong handicap, by family concord, and by a deep involvement with scientific and cultural life in Sweden in the twentieth century.

Family Background and Early Years

Axel Hugo Theodor Theorell, known as Hugo or Theo to his friends and colleagues, was born in 1903 in Linköping, a small town in southern Sweden located 280 kilometres south-west of Stockholm. His father was Thure Theorell, a medical doctor and one of the two founders of the Linköping Lasarett, which later became the regional university hospital. My grandfather was also responsible for a military regiment, and consultant physician at two local railway companies and a chocolate factory, as well as working as a private practitioner in Linköping. My grandmother Armida was a piano teacher, who fell in love with my grandfather while accompanying his baritone at a performance of Haydn’s The Creation in Linköping Cathedral. Happily, my grandmother’s feelings were reciprocated, and they married in 1900 and had three children: Eva; my father; and Elisabeth, or Lisa as she preferred to be called.

At 3 years of age my father fell ill with polio. Family law records show how even in the acute paralytic phase of the disease he showed indomitable fighting spirit by claiming: “I can move my eyes at any rate.” At the age of 9 he had a muscle transplant in his left thigh to prevent the recurrent falls that occurred as a consequence of the polio. The young Hugo was bullied by his classmates throughout his school years; however, his well-trained arm muscles were as strong as his legs were weak – powerful enough to do handstands on a surfboard and more than strong enough to grab two schoolmates with his arms and bang their heads together.

His school teachers had strong and odd personalities, most notably one teacher known as “Skutan” on account of his corpulence. (“Skutan” is a Swedish word for an old fishing steamboat with broad bows.) My father found it difficult not to laugh at Skutan when the teacher completed his daily dressing procedure in the classroom each morning, resulting in repeated expulsions from class. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Skutan predicted no future success for this young student.

While my father was convalescing after the muscle transplant procedure he began to play the violin. His first teacher was a friend from school, Sture Pettersson-Halvar, who contracted tuberculosis and sadly died in 1918. When his school friend died, Hugo received violin lessons from Charles Barkel, the first concertmaster in Norrköping, 40 kilometres north-east of Linköping. After a while Barkel moved to Stockholm and so my father had to make longer study trips, staying at his uncle Hugo’s apartment while there. To pay for his regular train journeys from Linköping, my father constructed a machine for making jigsaw puzzles, which he described briefly in his memoirs Växlande vindar (Changing Winds). With this contraption, a foot pedal made a spinning wheel rotate, and its rotation was transposed to the up- and downward movement of a saw blade. Unfortunately no photograph of this machine exists, but a puzzle, owned by my cousin H. Peter Hallberg, still remains. It took only 10–20 seconds to create puzzle pieces using this machine, and at a price of 2.50 Swedish kronor (SEK) per puzzle, the young Hugo earned several hundred kronor between 1918 and 1920, enough to finance his study trips to Stockholm for many months.

Author’s sketch of the young Hugo Theorell’s home-made jigsaw machine, based on the description provided in his memoirs, Changing Winds.

Kindly provided by Henning Theorell

|

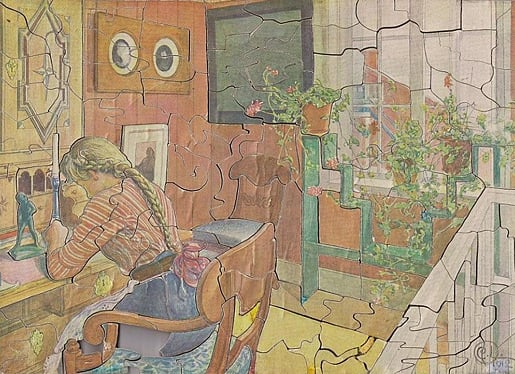

| Jigsaw puzzle created by Hugo Theorell sometime between 1918–1920. Kindly provided by H Peter Hallberg and Henning Theorell |

During his secondary education at the gymnasium in Linköping, Hugo was conductor of the school’s Music Society and chairman of its Scientific Society. In 1921, he took his Baccalaureate and achieved the highest possible mark in all subjects, the best pupil at the school that year. Being both musically and scientifically gifted, it appears that my father made the decision to pursue a living in science and remain an amateur musician with a lifelong challenge to develop his violin skills to a professional level. The autumn after his Baccalaureate he opted to do medical studies at Karolinska Institutet, a choice seemingly made at random and determined mainly on account of its low signing-on cost of 50 öre, or 0.5 SEK.

Around that time, his sister Eva was secretary to the Swedish mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler, and worked at the Institute that was named after him in Djursholm, north of Stockholm. Mittag-Leffler, who was in his mid 70s, made several trips to friends and colleagues in Germany, Austria, Italy and Finland between 1922–1925, accompanied by Eva, his physiotherapist Gerda Blomberg and, on many occasions, my father. In Berlin in 1922 they met Field Marshal Erich Ludendorff. My father, having bought a brand new camera, was asked to take a photo of the famous German general with Mittag-Leffler, but he got so nervous that the outcome was a completely blurred picture.

Mittag-Leffler saw in my father an extremely talented young man, and in 1922 he wrote a recommendation letter to the director of the University of Berlin (and recipient of the 1920 Nobel Prize in Chemistry), Walther Nernst, to request a scholarship for my father to study there. Whether Mittag-Leffler was prompted by my aunt or my grandparents remains unclear, but it appears he had his own reasons for this recommendation. He had read that the atomic energy released from 1 gram of aluminium was enough to push the whole British fleet to the top of Mount Snowdon, and so he wanted my father to serve as a spy and reveal how far the Germans had advanced in using nuclear power.

Nernst sent a polite letter in response (now kept in the library of the Mittag-Leffler Institute), in which he requested a copy of Hugo’s exam marks and noted that he would have to apply to the Ministry of Education for a working permit for two months study in the Department of Physics. When my father was eventually introduced to Nernst in Berlin, he was pushed into an enormous office by a uniformed guard with Nernst shouting: “Der Schwede soll ‘rein!” (loosely translated as “Now present the Swede to me!”). My father stumbled and fell to the floor, where he remained for the entire interview. Two months at the Physics department carrying out some simple experiments, however, was more than sufficient to prove to my father, and the professors, that his scientific inclination was not directed towards quantum physics.

Music & Marriage

My father returned to his uncle Hugo’s apartment while he carried out his medical studies in Stockholm. He continued his violin lessons with Barkel, and then from 1923 onwards with Professor Julius Rutström at the Royal Swedish Academy of Music. His younger sister Lisa was a pupil at Richard Anderssons School of Music, and in 1927, she introduced Hugo to one of her friends at the music school, Margit Alenius. Margit went on to study piano at the Stockholm High School of Music and with Edwin Fischer in Leipzig, Germany, and she had her first public performance as a concert pianist in 1928 at the Stockholm Concert Hall playing Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 14 in E flat major, conducted by Adolf Wiklund. Like my grandparents, music-making and love blossomed in concert and my parents married on 6 June 1931. Their honeymoon trip to Paris included, for my mother, one month studying the harpsichord with the Polish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. My mother subsequently became the first harpsichord teacher in Sweden.

My father Hugo and my mother Margit sailing in Stockholm archipelago around the summer of 1970. The boat was owned by their friend John Mattson, CEO of the building company John Mattson.

Kindly provided by Henning Theorell

Photographer: John Mattson

Though occupied with his scientific and family life, my father’s skills in violin playing advanced to a professional level, and he was able to play chamber music with world famous artists like Isaac Stern and Enrico Mainardi, or with musically talented Nobel Laureates such as Ernst Chain and Manfred Eigen. During one visit to see Linus Pauling at Caltech in Pasadena, my parents happened to meet Willem van den Burg, a cellist in the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra who had played with Albert Einstein. Van den Burg compared my father’s violin skills with Einstein’s as follows: “You play violin better than Einstein. His intonation and rhythm are as relative as his theory!”

Hugo’s influence on the classical music scene in Stockholm became considerable. He was elected chairman of the Stockholm Concert Association (Konsertföreningen) and vice president of the Royal Academy of Music. As first violinist in the Mazer Chamber Music Society, he performed at 650 Monday evening gatherings. The Mazer Chamber Society also performed for him. On Twelfth Night (5 January) 1965, my father and mother both broke their legs in a car crash. (My father’s fractured femur forced him to carry a supportive orthosis for the rest of his life.) Recovering at the Karolinska Hospital, our parents received a visit from four members of the Society who gave a performance of Mozart’s Dissonance Quartet. The music provided soothing comfort, not just to my parents. In a neighbouring sick room, a patient suffering from advanced colon cancer was able to fall asleep without opiate medication for the first time in months.

Incidentally, shortly afterwards, Feodor Lynen, who with Konrad Bloch received the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, broke his leg in a ski accident in the Swiss Alps. He wrote a postcard to my parents, who were still recovering in hospital, saying: “Dear Theo! From pure solidarity with you I have broken my femur skiing.” Surely a sign of true friendship!

|

| Rehearsal of Schubert’s Quintet in C major at our home in the 1960s. My father is sitting as first violin. Behind him from left to right: Claude Genetay (conductor of the Drottningholm Baroque Ensemble), counter bass; Leon Spierer (first concertmaster of the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra), second violin; Carin Luthander, cello; and Gereon Brodin (music director at the Swedish Broadcasting Corporation), viola. Kindly provided by Henning Theorell Photographer unknown |

Travel

Hugo had the fortune to travel widely, visiting colleagues and friends around the world, and collecting stories along the way. For instance, when my father first visited Linus Pauling in 1939, he travelled to the United States by passenger boat with, amongst other things, an unpurified extract of cytochrome c from ox heart. Upon arrival at New York harbour, he got stuck in customs. Having heard our father’s description of the nature and origin of the specimen, the zealous customs official happily let him pass with the remark: “Well, this must be meat extract. That’s listed in our tables, please pass!”

In 1942, at the height of World War II, my father travelled to Zurich to give a lecture. Looking for a free seat in a train overcrowded with soldiers, he found one, in a compartment where only a general and two commanders were seated. When a military policeman ordered him to leave the officer’s compartment, Hugo took some chocolate cake out of his pocket and offered pieces to the soldiers. The general exclaimed: “Ach Schokolade, das haben wir jahrelang nicht gesehen!” (“Ah chocolate, which we have not seen for years!”) When the military policeman returned to do his duty, the general shouted “Raus!”, or “Out!”, and my father was allowed to remain in the compartment with the officers.

My father was part of a World Health Organization committee of scientists who travelled to Israel and Iran in 1951 to explore the status of scientific and medical education in their universities. At the University of Jerusalem the dean took umbrage at their visit, stating that they did not need to be taught how to educate. Hugo then informed the offended dean that the Swedish word “lära” means both “teach” and “learn”, and that he was there to do both. Not that this trip was all work. One of the social events involved travelling through the Negev desert in a shaky caravan to lunch with a Bedouin sheikh, and being saluted with gunfire by Tuareg horsemen along the way. Over lunch, the secretary of the committee, a British pharmacologist who was travelling with his wife and 14-year-old daughter, received an unusual request. The sheikh wished to honour the committee by asking the secretary to allow him to take his daughter as his fortieth wife.

Hugo’s lab in Sweden welcomed researchers from all over the world, the long list of visitors including many Nobel Laureates and renowned scientists. These visits left more than a purely scientific impression. For instance, eight visiting researchers came from Japan over the years, and struggling to learn the English language, they fused their Japanese accent with our father’s regional, Östergötland variety of English. This made their linguistic traits rather recognizable: on hearing these Japanese scientists’ pronunciation of English, colleagues in institutions in other countries would often comment: “Oh, you must have been working with Theo!”

The Nobel Prize

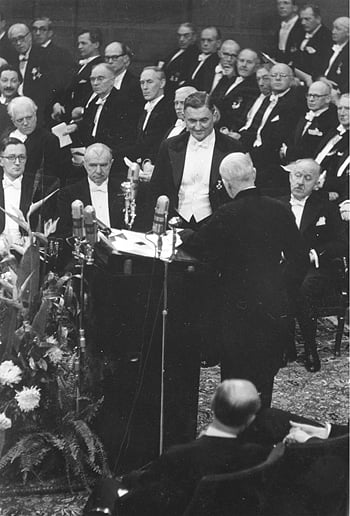

In 1955, my father was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, after having previously been nominated twice, in the 1930s and 1940s. Einar Hammarsten (my father’s mentor, a pioneer in the chemistry of nucleic acids and also uncle to the famous Finnish author of the Moomin books, Tove Jansson), gave the presentation speech at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony, concluding it with the following words: “A fertile imagination. An undeviating and critical accuracy. An astonishing technical skill. All scientists possess some of these attributes. Very few have all. You are one of these few.”

Einar Hammarsten’s presentation speech to Hugo Theorell at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony, 10 December 1955.

Kindly provided by Henning Theorell

Photographer unknown

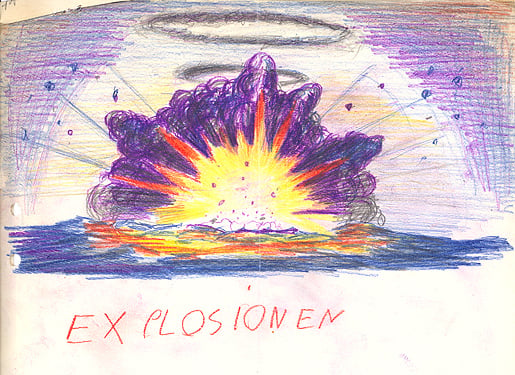

After becoming a Nobel Laureate, my father received several hundred letters, mainly from admirers or people requesting support for scientific projects, but one letter in particular pleased him greatly on account of its scientific ambition. A 12-year-old boy, Tom, from a suburb south of Stockholm, asked my father whether he and his friend Bengt had invented a new explosive called “silver gunpowder”, composed of three parts potassium permanganate, one part sulphur and four parts magnesium powder. Placed into an aluminium tablet tube in the backyard and ignited, this mixture produced an impressive explosion with two smoke rings one metre in diameter slowly rising up into the sky (as sketched by Tom, see below). The sketch had apparently frightened Tom’s parents so much that they forbade Tom and Bengt from continuing their experiments.

|

| Drawing from a 12-year-old boy called Tom, which shows the explosion caused by the “silver gunpowder” that he and his friend had created. Tom wrote to my father asking whether they had invented a new type of explosive. Kindly provided by Henning Theorell |

At the celebration of the 150th Anniversary of the Swedish Medical Society in 1958, Hugo as its chairman gave the jubilee lecture, entitled Berzelius och livskraften (Berzelius and the Life Power). During his lecture he said the following (my translation):

In his Year Book 1836, Berzelius wrote the following, while referring to Friedrich Wöhler’s at that time epoch-making experiments to synthesize, out of ammonia and cyan gas, as end products urea and three other chemical substances in the laboratory, without using kidneys, dogs, other animals or human beings. After reviewing a multitude of similar phenomena in nature, he states:

These reactions seem to be driven by a “catalytic power”, operating both in the dead and living matter. I can only suppose that it is a reflection of an inborn expression of the electrochemical power of material. We have good reason to suppose that in the living plants and animals, thousands of catalytic processes between tissues and fluids take place and produce the multitude of different chemical substances, to whose origin out of the common raw materials plant fluids or blood we never could realize a plausible cause. In the future we will discover the cause in the catalytic power of the organic tissues.

Berzelius had provided an astonishingly farsighted definition, given that his statements were made 90 years before the first successful crystallization of an enzyme, urease, by James B. Sumner. What Berzelius foresaw 200 years ago was simplified by the following definition that was formulated by my father:

A catalyst is a chemical substance which helps a chemical reaction without taking part in the final production, like the priest at a wedding.

As a professor and head of his own department of biochemistry, the Nobel Institute of Biochemistry, my father became a member of the Nobel Committee for Physiology or Medicine in 1937. Membership comes with the annual summer duty of peer-reviewing possible candidates for the Nobel Prize. All our summers were spent on Ljusterö, an island in the Stockholm archipelago, where my father had bought a traditional summer house called Tomtängen from his uncle Hugo. During the first summer month he always isolated himself in a room in a little annexed house, consumed with the task of investigating the Nobel Prize candidates. The task of reading and critiquing up to around 400 scientific publications and books per candidate was matched by the effort needed to transport the many crates of scientific volumes from Stockholm to Ljusterö. Before the 1950s the lack of a regular ferry meant that the crates had to be transported first by steamship from Stockholm to the local steamship bridge at Ljusterö, and then the final 800 metres of the journey to our boat bridge was completed by cow ferry.

Once this demanding review work was complete, he was finally free to devote time towards his hobbies: tending his roses, or sailing his yacht Thessan with his old friend from Linköping, Stig Danielsson. My father’s best friends from medical school also shared a passion for their archipelago country retreats, fishing and sailing yachts. Oscar Schuberth, who became professor and head of the Department of Surgery at St Göran Hospital, shared my parents’ love for classical music, though he was not an active musician. One of the deepest impacts that Oscar had on us was my father’s purchase of his small sailboat or “stjärnbåt“, in which we learned how to sail. Bertil Josephson, who became professor and head of the Department of Clinical Chemistry at St Erik’s Hospital, was from a Jewish family and he was very strongly supported by our parents when anti-Semitic sentiment in Sweden was rife between 1930–1945. Yngve “Gulle” Zotterman, who became professor in physiology at the Veterinary High School and specialized in the taste nerve functions, also became scientific secretary for the Wenner Gren Center scientific symposia.

My father at our summer house in Ljusterö in 1956, carrying out one of his favourite hobbies, tending to his roses.

Kindly provided by Henning Theorell

Photographer unknown

Conclusion

In this brief article I have attempted to provide a flavour of my father’s personality and attitude to life. Perhaps the best way of summing-up his outlook on life is to quote from a speech he gave during a broadcast to the Swedish public on New Year’s Eve, 1955, where he emphasized the need to care for our everlasting mental development. Citing Warren Weaver, director of the Natural Sciences division at the Rockefeller Foundation, my father said: “Peace for mankind does not mean rest, but rather a feeling appearing to anyone in the evening after a day’s well performed work.”

Further Reading

Theorell, H. Berzelius och livskraften. Nordisk Medicin 60, 1537–1540 (1958)

Theorell, H. Växlande vindar (Natur och Kultur, Stockholm, 1977)

Acknowledgements:

With permission to publish in other media from the editor, Professor Nils Erik Sjöstrand, this is an extended and revised version of the original article published in Svensk Medicinhistorisk Tidskrift 12, 177–190 (2008).

I wish to express my gratitude to a range of contributors to this article:

I am grateful to Professor Anders Ehrenberg, who saved our father’s handwritten 1934 laboratory notebook from being thrown away, identified his old co-workers and, together with Professor Hans Jörnvall, gave me invaluable comments.

I would also like to thank my brothers, Klas and Töres, for their continuous scrutiny, and our cousins: H. Peter Hallberg for help with the jigsaw puzzle; and Paul Hallberg and Agneta Norberg for saving and sending me correspondence from their mother, my aunt Eva Hallberg, to our grandparents during her travels with Professor Gösta Mittag-Leffler.

I am also grateful to the librarian at the Mittag-Leffler Institute for Mathematics for supplying Nernst’s letter in response to Professor Mittag-Leffler, and to Anders Bárány at The Nobel Museum for supplying chapters of the Karolinska Institute history.

Finally, thanks to Paul Hallberg for his help in correcting the English version of this article.

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

First published 24 February 2011

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.