Fighting oppression with poetry

The Nobel Prize in Literature is not only for novelists. Several literature laureates have been recognised for their remarkable poetry, which they have used to share the fight against oppression. Laureates including Bob Dylan and Gabriela Mistral have penned powerful poems that distil important issues, such as women’s rights and colonialism, into visionary verse, as well as using rousing rhymes in lyrics to promote equality and peace.

“Poetry is (…) the physical self of the poet, and it is impossible to separate the poet from his poetry. […] He passes from lyric to epic poetry to speak about the world and the torment in the world through man, rationally and emotionally,” said literature laureate Salvatore Quasimodo who was an outspoken anti-fascist during World War II and strongly believed that poets should play an active role in highlighting contemporary struggles.

Several poets who have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature have used their talent to raise awareness and work for positive change.

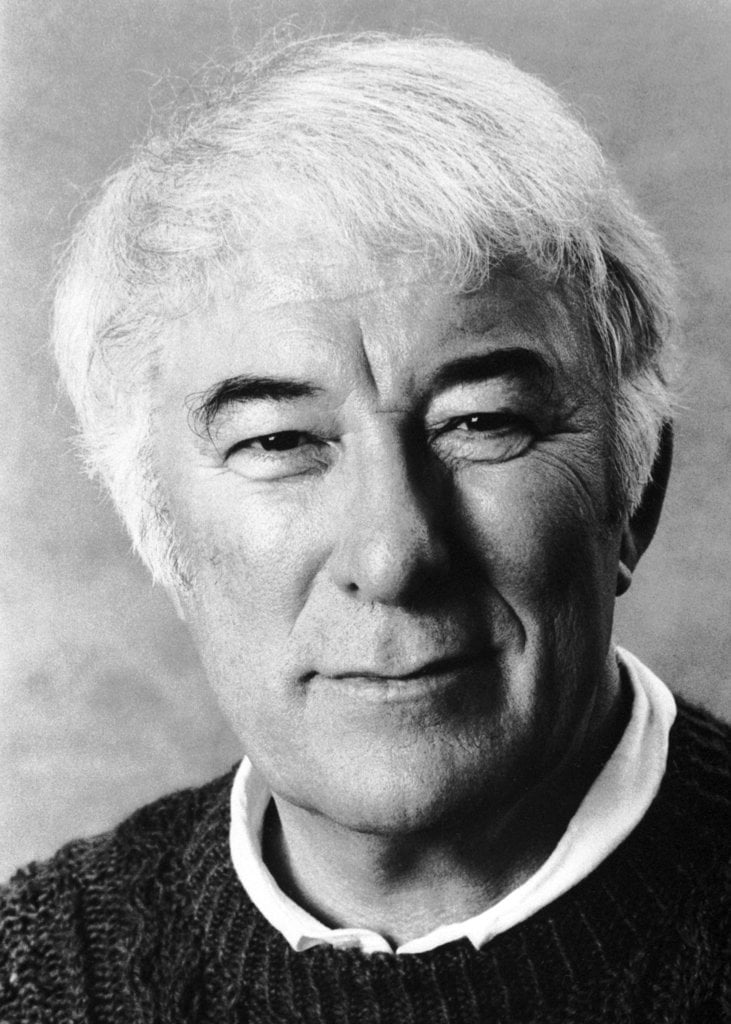

A dossier filled with heartbreaking stories of prisoners of conscience inspired literature laureate Seamus Heaney to write one his best-known poems, From the Republic of Conscience. His verses suggest that we should be lifetime ambassadors for a principled country and speak up on its behalf if its virtuous values are threatened. Heaney reportedly believed that art is driven by empathy and it is the role of the artist to give a voice to those who were oppressed and ignored. Poems, such as North, often explore Irish culture, history and identity. He is one of several literature laureates to explore the impact of colonialism in verse.

Questioning the ethics of colonisation

William Butler Yeats also examined the impact of colonialism in Ireland by immortalising acts of rebellion in poems including Easter, 1916, while the early plays and poems of Wole Soyinka, who grew up in colonial Nigeria, address political corruption, social injustice and human rights abuses in his home country. Soyinka writes in English and incorporates Western traditions in his work, but his poems and plays are rooted in his native Nigeria and the Yoruba culture of his family, with its legends, tales, and traditions. He talks about deep, human bonds in Lost Poems, while Civilian and Soldier explores the moral dilemma of a soldier trying to shoot a civilian, set in the Nigerian Civil war, or Biafra War. Soyinka penned an article calling for cease-fire, for which he was arrested and accused of conspiring with the Biafra rebels. He was held as a political prisoner for 22 months until 1969.

The poems of another literature laureate, Derek Walcott, who was born on the isolated volcanic island of Saint Lucia, often deal with Caribbean history, searching for vestiges of the colonial era. Both his grandmothers were said to have been the descendants of slaves.

“There is the buried language and there is the individual vocabulary, and the process of poetry is one of excavation and of self-discovery,” he explained in his Nobel Prize lecture. Coming from a bilingual island that was colonised by Britain and France, Walcott examines the cultural divisions of language and race in the Caribbean, as well as his own identity, in poems such as Sea Grapes and The Star-Apple Kingdom.

In A Far Cry from Africa, he writes:

“I who am poisoned with the blood of both

Where shall I turn, divided to the vein?

I who have cursed

The drunken officer of British rule, how choose

Between this Africa and the British tongue I love?”

It is the complexity of his own situation that has provided one of the most fruitful sources of inspiration. Three loyalties are central for him – the Caribbean where he was born, the English language, and his African origin.

In his Nobel Prize lecture, Walcott explained how deprived of their original language, colonised people in the Caribbean built upon “an old, an epic vocabulary” from Asia and Africa, as well as “an ancestral, an ecstatic rhythm in the blood that cannot be subdued by slavery or indenture.” He believes that the process of renaming places and finding new metaphors, is the same process that the poet faces every morning of his working day.

Opposing the oppression of women and children

Wolcott is not the only literature laureate whose ambiguous position spanning different cultures, languages or sociology roles has influenced their work. Gabriela Mistral – South America’s first-ever Nobel Prize laureate in literature – crossed over from teaching into the male-dominated world of politics, to earn respect as a diplomat and as one of Chile’s most celebrated poets.

Initially, she followed in her mother’s footsteps to work as a teacher until her poetry became known, borrowing the pseudonym, Gabriela Mistral, from her favourite poets, Gabriele D’Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral. She received the 1945 Nobel Prize in Literature for her lyric poetry which often draws upon maternal instincts.

Published in 1922, her debut poetry collection, titled Desolation, includes works that convey the stark realities of exploitation and poverty for children. Her poem Tiny Feet includes the lines:

“A child’s tiny feet,

Blue, blue with cold,

How can they see and not protect you?

Oh, my God!”

Reflecting her lifelong passion for teaching, Mistral wrote her second collection of poems titled Ternura (Tenderness) for mothers and children, while she gave the proceeds of her third collection – Felling – to help child orphans of the Spanish Civil War. She not only spoke for people mistreated and marginalised by society in her poetry, including women and children, but championed human rights on the international stage.

Shortly after receiving the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mistral became a delegate to the United Nations and played a key role in founding the United Nations Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), a voice for children in need. The teacher and poet turned diplomat worked tirelessly to improve women’s rights, reform education and fight tyrannies and challenge fascist dictatorships.

Fighting fascism and political tyranny

“O the chimneys

On the ingeniously devised habitations of death

When Israel’s body drifted as smoke

Through the air —

Was welcomed by a star, a chimney sweep,

A star that turned black

Or was it a ray of sun?”

This moving verse comes from Nelly Sachs’s poem, O die Schornsteine (O the Chimneys) in which the Jewish nation is represented as smoke drifting from concentration camp chimney, conveying a message of reconciliation and resurrection.

Several members of Sachs’s immediate Jewish family were victims of the Holocaust. She narrowly escaped the same fate. She was interrogated by the Gestapo and summoned to a ghetto, writing about the Nazis, “when the great terror came / I grew mute —”.

In the summer of 1939 as the Nazis tightened their grip on the German population and the world edged closer to war, a friend of Sachs’ visited literature laureate Selma Lagerlöf in Sweden to ask her to secure a sanctuary for Sachs and her mother. Sachs was a fan of Lagerlöf’s magical tales and had exchanged letters with the Swedish writer since her youth. Lagerlöf reportedly petitioned Prince Eugen of Sweden to secure emergency exit visas and Sachs escaped Nazi Germany with her mother on one of the last flights to Sweden during the war. They arrived in the spring of 1940, but sadly Lagerlöf had died. “We breathed the air of freedom without knowing the language or any person,” Sachs explained in her Nobel Prize banquet speech, adding “To me a fairy tale seems to have become reality”.

Having been forced to flee her homeland, Sachs frequently wrote about exile and transformation; themes examined in Jewish texts. Her poem In Der Flucht, (Flight) includes the lines, “In place of home / I hold the metamorphoses of the world –.”

The Nazi persecution left deep scars in Sachs’s psyche and also influenced her writing. She borrowed subjects for her poetry from the Jewish beliefs and mysticism, but her authorship is also strongly coloured by Nazi persecution of the Jews, with the horrors of the death camps as its ultimate expression.

Singing for civil rights and peace

Bob Dylan expresses a longing for justice and peace for marginalised and oppressed communities in song, with the lyrics of his earlier songs incorporating social struggles and political protest.

As a teenager, the American singer-songwriter was influenced by the early authors of the Beat generation and developed a passion for American folk music and blues, including Woody Guthrie, whose music rallies against fascism, racism and other injustices.

On 28 August 1963, 250,000 demonstrators marched to the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his famous I have a dream speech. Fewer people know that Dylan, (who was now famous having released his second studio album) played at the event, effectively opening for the peace laureate. He sang Only a Pawn in Their Game, about the recent assassination of the civil rights leader Medgar Evers, and Blowin’ in the Wind, which includes the famous lines that struck a chord with the Civil Rights movement, “Yes, and how many years can some people exist / Before they’re allowed to be free?”

Blowin’ in the Wind was also adopted by the Vietnam anti-war movement, with its lines, “Yes, and how many times must the cannonballs fly / Before they’re forever banned?” while many people interpreted lyrics in The Times They Are A-Changin’ as protesting the war and the unpopular draft.

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one if you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin.’

Having penned the lyrics during the Vietnam War, Dylan has performed it hundreds of times since. The compelling cry for positive change remains relevant today, while Blowin’ in the Wind is one of the best-known songs calling for peace.

Despite writing in different styles for different reasons, literature laureates have used their poetry to give voice to the oppressed and call for a better world, from the pages of poetry books to performances in front of thousands of people.

In their own distinctive ways, they all believe that the times they are for changin’.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.