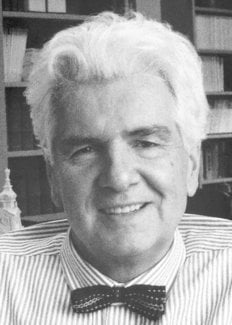

Günter Blobel

Biographical

In 1936, when I was born in the small Silesian village of Waltersdorf in the county of Sprottau in the then eastern part of Germany, now part of Poland, the fine structure of the cell was still an enigma. After 300 years of staring through light microscopes, essentially all that biologists had learned was that the cell was delimited by a plasma membrane and contained a nucleus. Staining procedures had revealed other distinct territories in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus, but their fine structure remained unknown. A dramatic revolution occurred in 1945, when Keith Porter, Ernest Fullam and Albert Claude at the then Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City introduced the electron microscope to look at cells. The first structure they saw was a lace-like network in the cytoplasm that they termed the endoplasmic reticulum. This discovery formed the foundation for my future scientific career.

1945 was also a turning point in my life. Until then my childhood was a perfect 19th century idyll. In the cold and snow-rich Silesian winters there were hour-long rides on Sundays in horse-drawn sleighs to my maternal grandparent’s farm to have lunch and to spend the afternoon. The house was a magnificent 18th century manor house in the nearby Altgabel with a great hall that was decorated with hunting trophies. In the summer, of course, horse-drawn landauers were used as means of transportation. The way to school was a long one. We went there on foot and as a pack, usually consisting of one or two of my seven brothers and sisters and of children from neighboring houses.

At the end of January 1945, we had to flee from the advancing Russian Red Army. My father, a veterinarian stayed behind for a few more days and left only hours before the Red Army moved in. My fourteen year-old brother, Reiner, drove my mother, my youngest brother, an older brother, the two younger sisters and me in a small automobile to relatives west of Dresden in Saxony. On the way there we drove through Dresden. We entered the city from the eastern hills. Its many spires and the magnificent cupola of the Frauenkirche (die Steinerne Glocke, the Stone Bell) were a magnificent sight even for the untrained eye of a child. Driving through Dresden, I still remember the many palaces, happily decorated with cherubs and other symbols of the baroque era. The city made an indelible impression on me. Only a few days, later, on February 13, 1945, we saw from a distance of about 30 kilometers a fire-lit, red night sky reflecting the raging firestorm that destroyed this great jewel of a city in one of the most catastrophic bombing attacks of World War II. It was a very sad and unforgettable day for me.

The months before and after the end of World War II were chaotic and miserable. None of my relatives had enough space to accommodate our large family leaving us divided among several relatives in different villages. There was no communication and little food. On September 9, 1945, we learned of the death of my beautiful oldest sister Ruth who, at age 19, was killed in an air raid on a train she was travelling in on April 10, 1945. She was buried in a mass grave near the site of the attack in Schwandorf, Bavaria. Ruth was born when my mother was just 20. The two had a sisterly relationship. My mother grieved over Ruth’s death until the end of her own life.

Fortunately, things took a turn for the better, when my father was able to continue his veterinarian practice in the charming medieval Saxon town of Freiberg. Most members of our family were reunited there by 1947. We lived in a nice villa surrounded by a large garden on the edge of town. My way to school was along the old medieval city wall. For only 40,000 inhabitants, Freiberg had a rich cultural life with a 175 year old theater. Most impressive were the musical performances in the magnificent gothic cathedral, the Dom, with the splendid great Silbermann organ. Each week Bach cantatas were performed. The great choral works of Bach, Mozart and Haydn were regularly performed and at the highest artistic level at the major religious holidays. I even participated in singing in the cantus firmus of Bach’s Matthäus Passion. So, it was almost like a 19th century idyll again, this time in a small medieval town instead of a country village.

However, there was now the ever more oppressive regime of East Germany to deal with on a daily basis. When I graduated from high school in 1954 I was not allowed to continue my education at a university because I was considered a member of the “capitalist” classes. Fortunately, at that time, i.e., before the Berlin Wall, it was possible to escape and to travel freely to West Germany. So, on August 28, Goethe’s birthday, I left Freiberg for Frankfurt on the Main in West Germany. The train left in the morning and in the afternoon it passed Weimar, where Goethe spent most of his life, and then Eisenach, where Bach was born and in the evening it arrived in Frankfurt, Goethe’s birthplace.

I studied medicine, beginning in Frankfurt and then in Kiel, München and Tübingen, graduating in 1960 from the University of Tübingen. Although I completed two years of internship in various small hospitals, I decided against continuing my medical training. I was much more fascinated by the unsolved problems of medicine than by practicing it. Fortunately, my oldest brother Hans had a similar experience in his field of study, veterinary medicine. He had obtained the prestigious Fulbright Fellowship to study in the U.S., continued his training there in microbiology and rapidly achieved the rank of full professor at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. He was extremely sympathetic to my dilemma and helped me to secure a graduate fellowship to study either with Khorana or with Van R. Potter. So, in 1962, I sailed to Montreal on a German steel freighter, and from there drove to Madison to arrive on a beautiful late day in May. Potter was a marvellous mentor, witty, energetic and stimulating. I graduated in November 1966, and decided to join George Palade‘s Laboratory of Cell Biology at the Rockefeller University (formerly the Rockefeller Institute). The revolution that began there in 1945, and that led to the discovery of all the major structures of the cell continued in the realm of relating cellular structures to specific cellular functions. My arrival there coincided with the end of this second phase and the exciting beginnings of a third phase, the molecular analysis of cellular functions (see below). I was fortunate enough in helping to initiate this third phase of analysis which is still in full swing.

George Palade has been my most influential mentor, a good friend and a wonderful colleague. He taught me how to conceptualize a collection of disparate facts, to formulate working hypotheses and to design experiments to test these hypotheses. I am greatly indebted to him.

In New York I married Laura Maioglio. Laura studied art history and, at her father’s death, took over Barbetta Restaurant founded by her father in 1906. Laura has introduced me to many artistic pleasures that I had not experienced before. She greatly encouraged me in my work and never complained about the many hours I spent in the laboratory.

In 1994, I founded Friends of Dresden, Inc., a charitable organization, with the goal to raise funds in the U.S. to help rebuild the Frauenkirche in Dresden. The rebuilding of many of the historic monuments of Dresden is one of the most exciting consequences of German reunification and the liberation from communism. It is a childhood dream come true.

It was one of the great pleasures of my life to donate the entire sum of the Nobel Prize, in memory of my sister Ruth Blobel, to the restoration of Dresden, to the rebuilding of the Frauenkirche and the building of a new synagogue. This donation also serves to express my gratitude to my fellow Saxons. They received us with open arms when we had to flee Silesia. I spent a wonderful period of my life there and they gave me a thorough and valuable education. A few thousand dollars will also be donated for the restoration of an old baroque church in Fubine/Piemonte/ltaly, the home town of my wife’s father, Sebastanio Maioglio. We have spent many happy summers there in the parental home of my wife.

Günter Blobel died on 18 February, 2018.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.