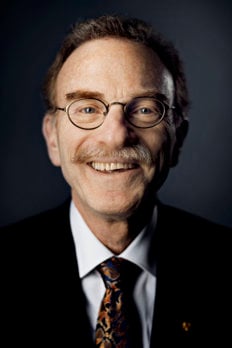

Randy W. Schekman

Biographical

Ancestors

The Russian Revolution and the growing influence of the Soviet empire stimulated a migration of Jews to America and Israel. My father’s father, Norman, followed his brother Nathan to Massachusetts where he enlisted in the British foreign brigade to fight in Palestine. He returned to the US and settled in Minnesota, along with a growing Jewish community in the Twin Cities. He met and married my grandmother, Rose, after whom I was given the name Randy, or Ruvain in Hebrew. My grandparents raised their children, my aunt Helen, my father Alfred, born in 1927, and my uncle Arthur in St. Paul. My grandfather had several careers; one I recall hearing about was as a traveling salesman selling clothing to farmers in the agricultural areas around the Twin Cities. My grandmother Rose died tragically of a stroke just as my father met and dated Esther Bader, a young high school student living on the north side of Minneapolis, then an enclave for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. They married in 1947 at the tender ages of 20 for my father and just 18 for my mother.

My mother’s parents, Raymond and Ida, grew up in a village in Bessarabia, which at the time was part of Romania, but which is now Moldova. My grandfather became a tailor, my mental image of which will always be fixed by the character Motel from “Fiddler on the Roof.” He was drafted onto the Romanian Army as a tailor and then by some stroke of good fortune won a lottery to immigrate with my grandmother to the US in 1927. Most of the members of their families were slaughtered in the Nazi takeover of Eastern Europe in the early years of WWII, but some managed to escape to Israel where a branch of our family lives today. My grandparents landed in Providence, Rhode Island and found their way to New York City. My grandmother was uncomfortable in a big city, so they sought out an adopted member of my grandmother’s family who had previously migrated to Minneapolis, where they ultimately settled and had two daughters, my aunt Mary and then one year later in 1929, my mother Esther. The family struggled to get by in the Depression, made worse by the illness of my grandmother who contracted tuberculosis and was taken to a sanitarium for a couple of years, during which time my mother and her sister were sheltered in an orphanage so that my grandfather could work as a tailor to cover the family expenses. Many decades later, years after my mother died, I learned from Rodney Rothstein, a fellow yeast geneticist, that his mother had befriended my mother and aunt during their years in the orphanage. I had the surreal experience of meeting Mrs. Rothstein at a special occasion where Rodney was honored and she recounted her memories, some 70 years later, of my mother during that time in the early 1930s. I will never forget embracing Mrs. Rothstein as a living memory of the mother I so cherished.

Early years in Minnesota

My parents took an apartment in St. Paul and I was born a year later in 1948. We then moved to another small apartment on the north side of Minneapolis, probably so that my mother could be closer to her parents. My sister Wendy was born in 1950 and my earliest memories are of the two of us as infants in cribs in that small apartment. My sister and I occupied the one small bedroom and my parents slept in the living room, which doubled as the dining room. My aunt Mary married Marshall Kopman, and for two years they lived together in the second bedroom of my grandparent’s home, probably no more than a mile away from our family apartment.

My oldest cousin Michael was born around that time and I am told – but do not recall – that I walked by myself to my grandparent’s home to see him, much to the horror of my parents. In the first years of my life, it was clear that I was shorter than my peers so my mother, who was quite combative as a child, decided that I needed to learn self-protection. She claimed, but again I do not recall, that she tried to teach me to hold up my fists in a threatening gesture, but it may have backfired when I resorted to the use of the top of a garbage can when I fought with a local child.

We remained in that apartment for several years. My father then designed and had built a small three-bedroom home of less than 1000 sq. ft. a couple of miles away, but still in the north side area just a block away from a home my uncle Marshall had built for his family. During the six years we lived on Upton Avenue, the Schekman family grew with two more boys, my brothers Murry and Cary, and the Kopman family grew with two girls, Jodi and Robin. We were a close knit family with daily activities revolving around playtime with my cousins and friends from the neighborhood, school at the Jewish community center and John Hay Elementary School, and afternoon Hebrew lessons at a religious school just down the block from my grandparents. The regular highlights were Friday evening Sabbath dinners at my grandparents’ home, holidays at the synagogue, a conservative congregation that my grandparents joined. My fondest memories are of drives to the countryside for an ice cream cone, occasional sleep overs on the porch at my grandparent’s home, but most of all, our annual trips to a cottage on a lake in Northern Minnesota, where my grandfather would take us fishing in a boat in pursuit of sunfish, walleye, crappie and the special treat of early morning trolling for northern pike. We lived and associated exclusively with other Jewish families and I was unaware of anti-Semitism until one day on my way to the Jewish Community Center, an older kid slugged me in the stomach when he learned where I was headed.

I have fewer memories of my father’s family. We would occasionally see his father and new wife, Evelyn, a dear woman who was sweet to the children and whom I grew to love in later years on a high school trip to Florida where she and my grandfather moved for retirement, and then later, after my grandfather died, on a visit to her sisters and their families in the New York area. My father’s younger brother Arthur lived with us briefly in the Upton Avenue house. We had more social occasions with Arthur and my aunt Carol and their children, Scott, Ronnie and Lorrie when they moved to Southern California in the 1960s. My father’s sister Helen moved to Columbus, Georgia and raised a family of five boys, whom I am sorry to say we almost never met for family events, other than one trip with my wife and son and my parents to a meeting in Atlanta in 1987.

I have only vague memories of any particular academic interest during those years in Minnesota. My father was a mechanical engineer working at General Mills. He was drafted after the war, but never left the country after boot camp and had attended the University of Minnesota on the GI bill. My mother worked part time in a department store during and after high school, but did not attend college. It was clear that the family valued learning and college for all the children was always an expectation, but any particular professional goals beyond college never entered my mind. I remember a casual interest in astronomy and I still have some electron microscope (EM) pictures of bacterial viruses that my father took which were used in particle size calibration at work. My casual reading was almost always of boy’s adventure stories.

I briefly belonged to a troop of cub scouts, but that sort of regimented activity had little appeal. Correspondingly, my most unpleasant memory of that time was of a military outfit that my parents bought for one of my birthdays.

Westward to California

In 1959, my father answered an ad for an engineering position in Southern California. On returning home from Los Angeles he announced that we would move at the end of the year to the great frontier of the Golden State. Neither of my parents had known anything other than Minnesota and yet my father somehow knew his future lay in the burgeoning computer industry of Southern California. My mother was traumatized by the move. She was emotionally dependent on her parents and could not bear the thought of such a geographic separation. For years after the move, she was inconsolable – when visits to Minnesota and/or of her parents to us in Southern California came to an end.

For me however, the move was a great adventure. We packed up the car and drove off in the deep cold of December 1959, traveling through snow flurries in the Midwest over the 2,000 miles to Los Angeles. The weather delayed our excursion and when we finally arrived on December 31, the reservation my father had made at a motel was cancelled and we had to scrounge for a single unheated room where the children bundled into one bed for warmth on New Year’s Eve. Still, Southern California was a dream with the network television studios just down the block from the motel we occupied for several weeks before moving to a rental home in Pacoima. I still recall with awe my first glimpse of the vast Pacific Ocean and the maze of freeways, not yet impassable with the choked traffic of today.

In 1960, my father purchased a new tract home in Rossmoor, then a new development in western Orange County, just adjacent to Long Beach. I had the privilege of my own bedroom where I hung out for long hours listening to the daily radio broadcasts of the LA Dodgers and their famous – and still active – announcer Vin Scully. My hero, indeed the hero of the entire Jewish community, was Sandy Koufax, the greatest pitcher of his generation. Those great World Series championships, especially the shutout of the Yankees in the 1963 World Series, are cherished memories that an impressionable child can never forget. On the other hand, although I have now lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for most of my life, I can never forgive the Giants and their infamous pitcher Juan Marichal who took a bat to the head of the Dodger’s great catcher Johnny Rosboro during a tense moment in a game at Chavez Ravine in 1965. I was a baseball nut but not at all athletic. My one year in little league ended ignominiously with a strike out on a bad pitch that I never should have swung at.

My father expected his children to be industrious and to work for extra money. I baby sat for the children of my parents’ friends, mowed lawns and held a paper route delivering news for the now defunct Los Angeles Examiner. My memories of school are not particularly strong. I remember the expectation of academic performance instilled by my parents, but until around 7th grade, I recall no particular interests or ability at the end of elementary and beginning of junior high school. That began to change when I received a toy microscope and collected a jar of pond scum from a local creek. I recall with amazement the rich microbial life seen in a drop of that pond scum, even just from squinting into the plastic lens of that toy.

The microbial world

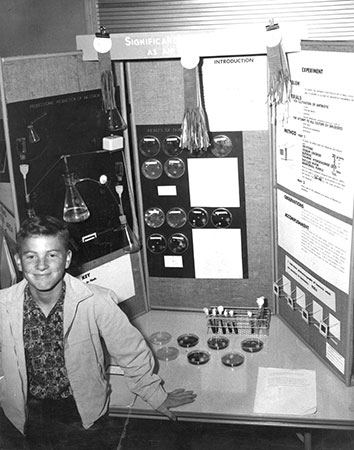

In the spring of 7th grade, I attended the school science fair and was captivated by the dozens of projects that the older students had assembled. The vivid memory of that simple event resonated somehow in a way that nothing else in my experience in school ever had. Here were simple but clearly individual efforts on display for recognition by fellow students, teachers and parents. In retrospect, this may have been the single event in my youth that fixed my path in science. In the following year, I spent countless hours looking into or projecting an image onto a sintered glass screen of paramecia and rotifers gliding or crawling across my field of view. I built a science project display based on my simple observations for my first entry in 8th grade, and although I recall no particular recognition for that work, I was nonetheless hooked, and the annual science fair became my one abiding academic passion through junior and high school.

Another revealing moment came that year when I recounted my excitement about these protozoa in a family conversation at the dinner table. My father, perhaps recalling his own experience with EM images of bacterial viruses, was dubious that anything of value could be seen in my toy microscope. At that point, I resolved to save and buy a student professional microscope using the money from my odd jobs.

Time went on, but I never seemed to reach my goal of $100 because my mother would borrow the money for family expenses. One Saturday I became so upset that after mowing a neighbor’s lawn, I bicycled to the police station and announced to the desk officer that I wanted to run away from home because my mother took my money and I couldn’t use it to buy a microscope. My father was called in and words were exchanged behind a closed door, the net effect of which was that we purchased my microscope at a pawnshop in Long Beach that afternoon! That microscope became my treasured possession for the rest of my years at school, but it was inevitably put aside as I went ahead to college and graduate school. Fortunately, my parents saved it and sent it up to my current home in the San Francisco Bay Area, where it languished in the dust for decades until the call from Stockholm at which point I realized it might be more interesting to visitors at the Nobel Museum. My old microscope is now on display, together with the tale of how it was acquired in a fit of childhood pique.

In 9th grade, a friend of my parents who worked in a hospital lab in Long Beach took an interest in my budding passion for microbes. She provided me with simple training in the classification of bacteria and valuable assistance in acquiring simple ingredients I would need to grow bacteria at home. I assembled a homemade incubator whose temperature was controlled by a light bulb hooked to a rheostat. I purchased simple supplies of glass petri plates, flasks and agar. Through my friend at the hospital, I was given units of spent human blood, which proved to be a rich source of nutrients for the growth of bacteria that were the subjects of my science fair projects over the next several years. I used my mother’s pressure cooker to sterilize and melt the agar and stored the spent human blood and my fresh medium in her refrigerator. In truth I didn’t really know what I was doing most of the time, but it certainly stimulated my reading of as many books on the microbial world as I could lay my hands on.

Just before I entered high school, my future biology teacher, Jack Hoskins, introduced himself as I stood in front of my project at the county science fair. Jack became my mentor during the next three years, and though his knowledge of experimental science was limited, he became a valuable source of encouragement outside of my family, who had much less knowledge of or interest in science. Indeed, we remained in contact through all the years since then – through to the morning of the Nobel Prize announcement when he sent a congratulatory message, expressing delight that he had lived to see this day. Back in high school, the peak of my effort was a fifth place prize in the senior life science division at the California State Science Fair, and an on-TV interview by Vin Scully, whose velvet voice of the LA Dodgers had entertained me for so many years.

As I dreamed of my future in college, I read such books as The Microbial World by Adelberg, Doudoroff and Stanier, and Bacterial Viruses by Gunther Stent. Indeed, as I explored the annual catalogue of courses at UC Berkeley I recognized the authors of these books as faculty members and wondered what opportunities I might have to learn directly from such individuals. The cost of college was foremost in the mind of my mother who thought it would be good enough if I lived at home and attended the local State College in Long Beach. However, I was certain that I wanted the more vigorous experience and peer group of a selective University, so I compromised on distance and applied to just one school, UCLA. In truth, UCLA also appealed because of the great basketball teams coached by John Wooden who had just recruited the best high school player of all time, Lew Alcindor (now Kareem Abdul Jabbar).

Stirrings of the life of a scholar

In the fall of 1966, I drove my motorcycle the 30 miles to UCLA where I took up residence in the student co-op dormitory along with my high school buddy Peter Wissner. The timing was perfect because just one week earlier my mother had given birth to my youngest brother, Tracey, and as hectic as college was, it would have been even more disruptive with a new baby back home. I threw myself into my studies and spent every waking hour in class or in study in a library. My courses were generally wonderful, particularly freshman chemistry then taught by a brilliant lecturer, Kenneth Trueblood, who received a standing ovation at the end of the term. I did well enough in that course to be admitted to an honors section for the third term, a course taught by Willard Libby, a Nobel Laureate who had won the prize for C14-radiodating of ancient materials.

The students in this class were clearly a cut above the others in my courses, and as a result I enjoyed my first taste of serious scholarship. Although it was inspiring to be taught by such a renowned chemist, Libby was not the effective lecturer we had experienced in Trueblood. But what made this class special was that each student was assigned to work in a Chemistry Department lab for the term. By chance, I was assigned to the lab of a new assistant professor, Michael Konrad, who had worked as a graduate student with Stent at Berkeley. Konrad assigned me to read a new book just off the press, entitled The Molecular Biology of the Gene, by James Watson. The book was a revelation to me and I read its paragraphs and chapters as though they came from a new bible of life. My project in the Konrad lab was simple enough: I hydrolyzed a sample of DNA and determined the base composition by chromatographic separation and UV absorption.

Although I had started UCLA with an aspiration to attend medical school and become a pathologist, the experience of my first year changed my outlook completely. I was disappointed that most of my pre-medical classmates were more interested in getting high marks than in the science itself. In contrast, the one term experience in Konrad’s lab combined with Watson’s book convinced me that my future lay in experimental science, preferably as an academic in a research university. The summer after my first year in college I worked with my father at his computer data firm. He had hoped to enthuse me about writing computer code, but I found it boring and my mind turned to how to pursue a basic molecular biology research project when I returned to UCLA for my second year. I cooked up an idea to look at the effect of a mild organic solvent, DMSO, on the uptake of viral DNA by bacterial protoplasts. After a couple of disappointing approaches to various faculty members, I found another new assistant professor, Dan Ray, of the then Zoology Department who was willing to gamble on me.

A path to discovery of molecular mechanisms

Dan had trained with Phil Hanawalt at Stanford studying bacterial DNA repair and then with Peter Hofschneider in Munich studying the replication of a small circular chromosome of the phage M13. I puttered around for a term trying to learn how to perform the experiments necessary to test M13 phage DNA uptake into E. coli protoplasts. Dan took me under his wing and gradually turned me to the interests he had in the mechanism of replication of the duplex form of M13 in cells infected with the phage. I was captivated by the idea that an experimentalist could use physical techniques such as velocity and density gradient separation of chromosomes extracted from infected cells to test models of chromosome strand inheritance during replication. Dan offered me a summer job and then generously listed me as a co-author on two papers he had prepared for publication.

Not many UCLA undergraduates worked in a research lab during that time, but I was happy to work alone well into the evening. Although my coursework was also going well, I increasingly began to feel that I was perhaps misplaced at UCLA, and that I might benefit by transfer to a school such as the University of Chicago that had a reputation for serious scholarship at the undergraduate level. James Watson himself had been an undergraduate at Chicago. Indeed, in the fall of 1967 I read Watson’s The Double Helix, which as much as his textbook had steeled my determination to live the life of a scholar in pursuit of a basic understanding of life. But as a simpler and much less expensive alternative, I learned of the University of California education abroad program and I applied and was accepted for a year at the University of Edinburgh.

I was excited to travel to Britain – I had never been out of the US – and in anticipation I asked a professor who taught a graduate course in genetics whom I might approach on the faculty in Edinburgh. I learned that the prominent bacterial geneticist William Hayes, had just started a new Medical Research Council unit in this research topic. I wrote to Hayes and he welcomed me to join the new unit, though he mistakenly believed that I would spend the year as a sabbatical visitor. I arrived to find that I had been listed on the opening program as a visiting faculty member from UCLA and was assigned my own laboratory space. They quickly realized their error but graciously provided me an opportunity to learn bacterial genetics from a Lecturer, John Scaife. I managed also to continue my studies on M13 phage and took the biochemistry course in the medical school in downtown Edinburgh. The year provided a wonderful opportunity to travel on the continent during the term breaks. However, I was ill prepared for the British style of examination that consisted of one comprehensive exam followed by an interview with the Biochemistry faculty. I survived by the skin of my teeth, but was appropriately upbraided by the faculty who relished the opportunity to take an arrogant Yank down several notches in my exit interview.

The most enduring influence of my year in Edinburgh was my acquaintance with Leonard (“Len”) Kelly, a graduate student in the lab next door in the Molecular Biology Department. Len shared correspondence with his brother Regis (“Reg”) who was then a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Arthur Kornberg, whom I knew to be the leading DNA enzymologist of this era. Reg had discovered that the DNA polymerase was capable of removing thymine dimers from UV-irradiated DNA in a repair-like replication reaction. The work was elegant and precise in a way that I had not experienced; I resolved to learn biochemistry from a master such as Kornberg.

In the months before I left Edinburgh to return to the US, I considered summer opportunities in the US prior to my senior year at UCLA. One possibility was the Undergraduate Research Program at Cold Spring Harbor (CSH). I would have relished the total immersion of that program, and the timing could not have been better with the discovery of the E coli DNA polymerase mutant by John Cairns who was then the director of the CSH lab. However, the summer stipend they offered was just enough to live on and I had to save money to pay for my remaining year of college. Instead, I took a summer position with David Denhardt in the Biological Laboratories at Harvard. The ferment of the Bio labs was intense with the Walter Gilbert and James Watson labs just down the hall. But the bickering and contentiousness of the atmosphere left me with a bad feeling about what it would be like to do PhD work in such a hypercompetitive environment. Nonetheless, I had a wonderful time in Denhardt’s lab and learned much to affirm my resolve to pursue a more biochemical approach to the study of DNA replication in graduate school. I left having done enough work to publish a first author paper in the Journal of Molecular Biology the following year.

Personal growth, loss and challenges in college and graduate school

My last year at UCLA brought emotional highs and lows. On the upside, I had the opportunity to meet Arthur Kornberg and to discuss my interest in the biochemistry of DNA replication and then in the spring of the next year, I was admitted to Kornberg’s department at Stanford for graduate school. But before that, just as I returned home from my summer at Harvard, I was greeted by my mother at the Los Angeles airport with the news that my sister Wendy had been diagnosed with acute leukemia and was given just months to live. Wendy’s rapid decline and our family’s anguish at her loss left a scar that is never far removed from my thoughts, even 45 years after her death. My mother was tortured by the loss of her one daughter and never fully recovered from the emotional blow.

Perhaps in reaction to this trauma in my life, I threw myself into the work back in Dan Ray’s lab at UCLA and didn’t bother with many of the lectures in classes that I had to complete in order to graduate. As a result, my grades declined and I was placed on academic probation for the second of the three terms of the year. Indeed, I failed German twice and left UCLA without actually having graduated. The registrar at Stanford took a dim view of this gap in my record and it was not until a sympathetic Dean back at UCLA waived that requirement – thus allowing me to graduate – that I was able to look ahead to my graduate career.

My personal life at Stanford was also a mix of highs and lows. Although I was thrilled to be in such an exciting environment, my immaturity led to personal isolation. Most of my fellow PhD students came from elite private universities and I felt insecure as one of the few students from a public university. Kornberg once asked me why I hadn’t enrolled in a “better” school, to which I responded that it was the best my family could afford. But looking back at what I was able to accomplish then, and now after nearly 40 years at UC Berkeley, I can state with confidence that I had the best preparation and that our great public institutions, the University of California in particular, offer educational and real life experiences that are second to none.

After a period of personal decompression (I was placed in small lab room by myself as penance for my obnoxious behavior), I slowly developed great friendships that have lasted a lifetime. Costa Georgopoulis, a postdoctoral fellow in Dale Kaiser’s lab, took pity on me and invited me to join a group for a camping trip in a nearby state park. Costa deflated my ego by calling me a turkey, a term of endearment that seemed to fit and which stuck for some years. But my greatest friendship came when Bill Wickner joined the Kornberg lab in 1971. Although we were in a somewhat competitive situation in the first months of his time at Stanford, I will never forget the favor he did me when, after I made an aggressive remark, he lifted me from the floor by the front of my shirt and told me to settle down!

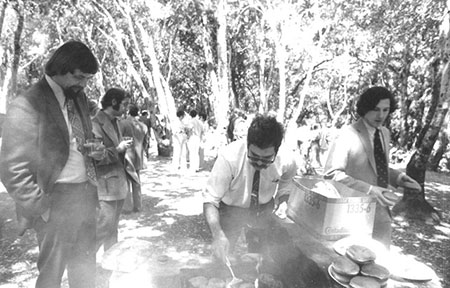

But Bill did more than that for me. After a few more months of intense and close cooperation, he could see that my personal life was going nowhere so he and his wife Hali conspired to find a suitable mate for me. After one failed effort at matchmaking, Bill had a call from a former girlfriend, Nancy Walls, whom he had dated in Boston. Nancy had completed her training as a nurse at Massachusetts General Hospital and decided to make a clean break to the West Coast. Feeling lonely herself, she called Bill at Stanford but learned that he had in the meantime married Hali, but he had a lab partner who needed distraction. I still remember our first date at a Greek restaurant in San Francisco and our first kiss goodnight. Nancy and I grew close quickly as these things happen when you are young. We moved into a small duplex home in Palo Alto and Nancy took a job as a nurse at Stanford Hospital. We would meet for a goodnight kiss while she was on a night shift and I worked into the wee hours of the morning in the lab. Nancy and I married in a ’70s style outdoor wedding in Huddart Park in Woodside, near the Stanford campus. Our years at Stanford were fulfilling in every way. I grew emotionally secure in a loving relationship and even with the intense and sometime acrimonious battles I had with Kornberg, I left graduate school equipped with the intellectual and technical skills that made my subsequent career possible.

Nancy took classes at a local community college with the goal of obtaining a BA in nursing. As we considered our next move for my postdoctoral training, she felt we should remain in California where her course credits would be recognized by a state school. I arranged a postdoctoral position with SJ Singer at UC San Diego and we moved south for what would be a short two-year stay in San Diego. In spite of the issue of course credit, Nancy enrolled at private school, the University of San Diego, and completed the requirements for her BA degree. She worked as an intensive and coronary care nurse, but we both missed Northern California, so when the opportunity came for a position at Berkeley, we moved back north and have remained ever since.

Family life and career at Berkeley

We settled into a family life in El Cerrito, a bedroom community just north of Berkeley. Nancy took a job at Alta Bates Hospital in Berkeley and we saved as much as possible to afford a home which we purchased in 1977 – and where have lived to this day. Our son Joel was born at Alta Bates in March of 1978, and our daughter Lauren was born in Basel, Switzerland in November 1982, during a sabbatical year in Basel that Bill Wickner, I and our wives had arranged for the year after I was granted tenure at Berkeley. Both of our children inherited a talent and taste for classical music from Nancy, who had played the saxophone in school and her mother Beatrice, who played the violin, so it seemed natural to expose the children to piano and other forms of musical training. The years of our family life sped by, enriched by the music of our talented children who filled our home with beautiful sound. Joel took up the clarinet and never let go. His passion grew into a career as a classical musician, currently in the Grand Rapids, MI Symphony Orchestra. Lauren sang in youth choirs that traveled the world, but she found more of a calling in economics, management and the business world, though she remains active in a semi-professional choir where she lives in Portland, Oregon.

Nancy worked full-time and then part-time when the children were young, and she may have remained active in nursing, but life intervened and at the relatively young age of 48, she was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease (PD). In her case, the disease progressed quite slowly and was effectively controlled by medication, but inexorably the physical symptoms worsened. In 2009, she had neurosurgery to implant electrodes in a treatment called Deep Brain Stimulation. This procedure worked remarkably well, and together with medications, her physical symptoms are unusually mild for someone now 18 years post-diagnosis. Unfortunately, this awful disease comes with other disabilities and in her case, dementia set in, which has slowly but inexorably sapped her memory and independence. Two years ago, her dementia was diagnosed as an atypical form of PD called Diffuse Lewy Body Disease for which no effective treatment exists. Life continues and we remain devoted to each other after nearly 42 years of marriage, but I fear for the future as her condition worsens year by year.

My parents rejoiced in the birth of my children, their first grandchildren, and our occasions together were filled with pride in the musical accomplishments of Joel and Lauren. As my career flourished, my parents tagged along to every special event and award ceremony and they fully expected to include a trip to Stockholm at the end of the rainbow. But in 1996, my mother was diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor, which took her life two years later at the age of 69. This loss struck my father even more deeply than the loss of his daughter / my sister. However, with time he recovered and with the help of a support group he met a wonderful woman, Sandy, who had lost her husband to heart disease. They were married within two years and continue to live happily together in a new home in Southern California.

Sandy and my Dad were the first people I called on that fateful early Monday morning of October 7, 2013. Among the many thrills of our memorable trip to Stockholm, I will never forget having my father rise to receive my appreciation in front of the thousand people who attended my Nobel Lecture. He never faltered in his certainty that I would someday receive that recognition. In honor of my sister and mother, I donated my Nobel Prize funds to create an endowed chair, the Esther and Wendy Schekman Chair in basic cancer research at UC Berkeley.

An appreciation

In my Nobel essay, I described in detail the contributions of my students and postdoctoral fellows that led to our dissection of the secretory pathway in yeast and the many molecular insights that developed from our discovery of the SEC genes and their protein products. I had the good fortune to attract some of the finest young scholars from around the world to join in that effort. But I owe at least as much to the many colleagues at Berkeley who taught me how to be a constructive citizen of science. Among them, I wish to offer a special tribute to Dan Koshland, Howard Schachman, Bruce and Giovanna Ames, Bob Tjian, Jeremy Thorner and Mike Botchan. They offered counsel and friendship that has enriched my life as a scholar and teacher.

During that nearly 40-year adventure, I observed a sea change in the attitudes and acceptance of women as scholars in the academic community. Gone are the days when women were relegated to “adjunct” status in couples seeking academic appointments. Instead, I found women who joined our department and my laboratory who had the highest standards and drive for achievement. Several who stand out in my experience are Susan Ferro-Novick, who was and continues to be as ambitious as they come, Linda Hicke, whose experiment I detailed in my Nobel Lecture as one of the most memorable in my experience at Berkeley, Nina Salama, who completed the detection and purification of the COPII proteins, Sabeeha Merchant, who came for a brief sabbatical and has remained a best friend and confidant ever since, and Liz Miller, who solved the mystery of cargo selection by the COPII coat. Science will never be the same now that women have taken a proper role in creative scholarship.

It is hard to believe that nearly 40 years has elapsed since that first day when I walked into the Biochemistry building to begin my career at Berkeley. The memories of all those years could fill a book, but I must bring this biography to a close with an appreciation of all that my family, friends, students and colleagues have done to make this a “Wonderful Life”, as the director Frank Capra so movingly captured in the movie of that title. I am not a religious person but I feel that I have been blessed with opportunities and people who have enriched my life immeasurably. This essay is dedicated to those who have passed on and to the love of those who now sustain me.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.