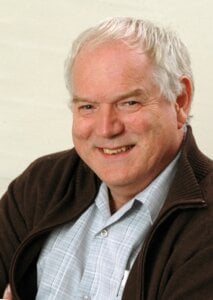

Interview with Michael Houghton, February 2021

“We’re all on a learning curve”

Nobelprize.org interviewed Michael Houghton on 1 February 2021. We spoke with him about his journey into science, his advice for students and the importance of persistence.

Photo courtesy of University of Alberta

What did you want to be when you were younger? Did you want to be a scientist?

Michael Houghton: Yes, I did. At high school I was interested in biology. I was interested in physics. So when I got my A-levels, I was trying to figure out what to do: physics or biology. But I didn’t get a very good grade in my physics A-level. So I thought, ‘Well maybe I’m not going to be too good at that’.

I went to the local library where I lived and looked at all the various career choices. I spent a week in the library thinking seriously about what career I wanted. I got to ‘M’ – microbiology – and I read about Louis Pasteur’s work and his life story. And then I thought, this is what I want to do. That was when I think I decided I was going to do medical research.

What was it about Louis Pasteur’s story that spoke to you?

I think two things. His daughter died of bacterial disease so obviously with his work, he was able to prevent that in so many people. There was that medical innovation and altruistic aspect to his life along with his tragedy. But also it was very interesting to actually study the mechanism of bacteria and life organisms in general. I was very interested in the difference between an organism and a rock. I found the organism much more interesting than the rock. As you change and develop through life, you realise rocks are very interesting, you can get a lot of information from rocks! But at the time I was more interested in living organisms than physical objects.

Besides Louis Pasteur was there any other person in your life, perhaps a teacher or mentor, that influenced you to take the path you went down?

Not really but growing up in England, when the structure of DNA was elucidated in that magnificent work by Watson, Crick and Wilkins, the BBC ran programmes about it on Sunday mornings. I used to get up quite early on Sunday mornings just to watch it. That really influenced me too. I knew I wanted to do biology and medical research. And I also knew from listening to those programmes that I wanted to get involved with gene regulation – what these days is termed molecular medicine.

And that’s what you were interested in at university. What type of student were you? Were you very studious?

I started off studious for the first two terms, but then after that, I discovered a lot of interesting things to do socially! The usual student things – I played a lot of sport, drank a lot of beer and just enjoyed a much freer community for the first time in my life. I went to a traditional high school in the UK where you were told what to do, and often what to think. So being released into a really open community at the University of East Anglia, I wouldn’t say I went off the rails, but it was an important period of growth for me. But actually the work suffered!

Looking back is there any advice that you would give to yourself, or that you like to give to students who are starting to think about their career?

I feel like it’s very important to find what your passion is in life, find out what you’re really motivated to do, and it doesn’t matter what it is. It could be a ballet dancer. It could be a travel writer, but find out what really motivates you. Secondly spend a lot of effort on finding out because I think a lot of young people drift from one thing to another, to another. It’s okay to change but I think you’ve got to put a lot of thought into what you really want to do, and you’ve got to put some effort into that. It’s not an easy decision.

So in summary – find what you’re passionate about, find out what your vocation is and spend time and spend the effort to do that.

What makes you passionate about science and your work?

I like the idea of looking at disease and then working with other scientists to figure out ways to prevent that disease. I work at the level of molecular medicine, and there’s a lot of tools available to us now, a lot of methodologies and a lot of technology we can bring to diseases. I very much like exploring ways to solve disease. We have so many diseases that affect humans.

Although we’ve made progress, I don’t think it’s good enough. There are too many diseases that humans suffer from about which we know very little – Alzheimer’s, inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis. Cancer of course gets a lot of effort and there has been some progress there, but there are so many diseases that really afflict mankind that I feel we should be doing a better job on.

How does it feel to do work that has such a tangible impact on people’s lives?

It’s great. After our discovery of the hepatitis C virus, I organised an international meeting on the disease with a colleague in Italy. I remember sitting in the audience during the conference and hepatitis C virus was up there on the screen. And I thought, wow finally we’ve been able to identify a field and to have people all over the world, working on it, to actually help patients. That was a good feeling.

But it took us a lot of effort to find the virus, the best part of seven years. When you’ve been trying so, so long, so hard, it was very satisfying after spending so much work and effort. And there was a fair bit of pressure. It was done in a biotech company where the investors are always asking when, when, when, where’s the virus?

But the bottom line is if you can impact disease and prevent disease in patients, that’s what medicine is all about. Whether you’re a clinician or whether you’re a medical researcher, like me, that’s the most important thing. Everything else is just icing on the cake.

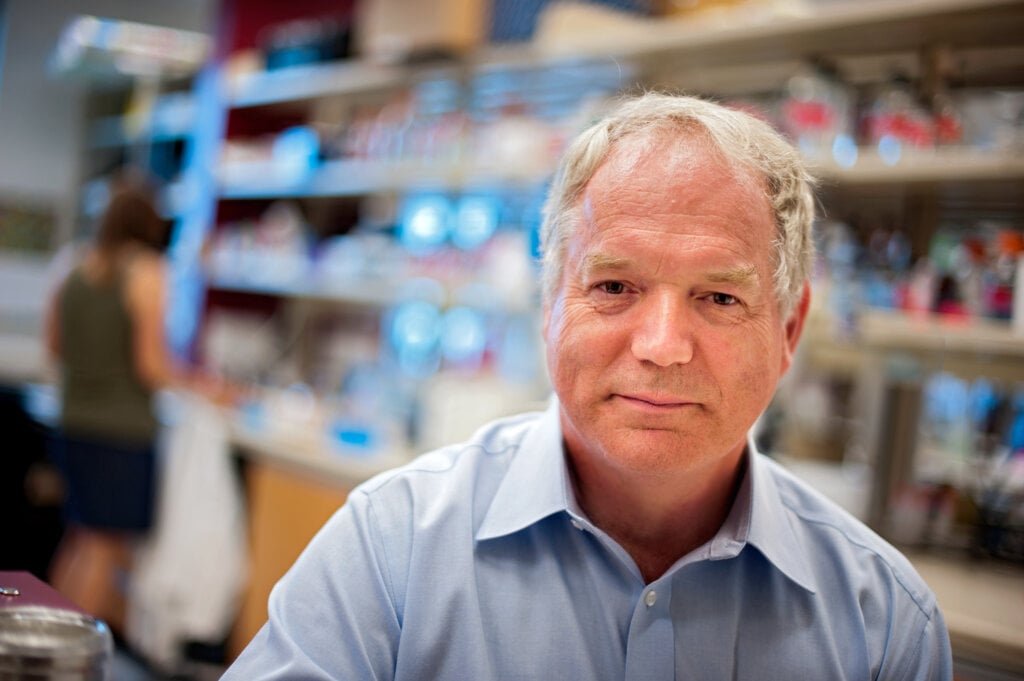

Dr. Michael Houghton in his lab at Li Ka Shing Institute of Virology

Photo Credit: Michael Holly, Copyright: ©University of Alberta

You mentioned that discovering hepatitis C took a lot of persistence. What qualities do you think are important to be a successful scientist?

I think for me, it’s working with good people. I think that’s important because you can kick ideas around with each other and often the best ideas come from chance, random conversations. You schedule meetings all the time to update progress and review problems, but it’s really the conversations around the coffee pot at work, or sometimes over lunch. It’s environments that are not scheduled that really stimulate the germ of, ‘well, okay, this is a direction we should take’.

I think number two is, as I said before, being very passionate about what you’re doing, because that gives you determination and that gives you the persistence. Persistence is very important.

What else? Good old fashioned hard work and getting the funding. It’s not easy getting funding for something like hepatitis C – seven years without making any progress. That’s tough to do in academia and it’s tough in industry because people want returns quite quickly.

So working with good people, persistence, determination, and don’t give up. If you think you have a good chance, a reasonable chance, don’t give up.

How did you manage to convince your company to keep going then?

That’s a great question. I think you always get conflicting opinions in any group of humans. Some people think it’s time to stop the program. Some people think even if we don’t discover it, we’ll be there and able to contribute to the growth of the field and in some way make a contribution, medically and commercially. And then other people feel, like I did, that it’s worth the effort. What else could I be doing that has the potential of trying to discover the hepatitis C virus?

So there’s a whole range of different emotions. There’s the commercial, there’s the impatience, and then there’s the philosophical: ‘what else could I be doing that was more important than trying to find a major virus?’

What keeps you going, when you encounter problems or failure?

I think first of all you’ve got to believe with realism that you have a real chance. You don’t want people trying to become astronauts and going to Mars if they don’t like heights! That’s an extreme example, but you’ve got to believe with some reality that you have a chance to do it.

If you feel confidence that you can do it when you have setbacks, which we had all the time for seven years. I was very philosophical about it. When colleagues showed me disappointing data often I would laugh and say, ‘Well, okay, that’s too bad. Let’s try something else.’ So good old human traits of confidence and persistence, that’s part of what the human race has, doesn’t it?

And outside of science how do you like to spend your free time? Is there something you do to feel more creative or relax?

I played a lot of sports since the age of four actually, so I love sport. I love cricket, it’s my favorite game. I used to play a lot of it at high school and at college and afterwards. Nowadays I just watch it!

And I’m interested in the world around us. We’re all on a learning curve. We’re still trying to figure out what we are and where we are. I read books on physics. I read books on cosmology. I’m very interested in understanding who we are. A sort of philosopher I suppose like millions of human beings – we’re trying to figure out what we are.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

First published: February 2021

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.