Interview with Charles M. Rice, March 2021

“Try and find something that you have a passion for”

Nobelprize.org met virologist and dog lover Charles Rice on 11 March 2021. We spoke about his path into science, what advice he can give to younger researchers and how he received the news about his Nobel Prize.

Why did you decide to pursue science?

Charles Rice: I think it’s really just fundamental curiosity. I’ve always been interested in sort of nature, biology and the outdoors, amongst many other things. So I think I was somewhat unfocused coming out of my early education. And that was certainly the case when I went to college. I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to do.

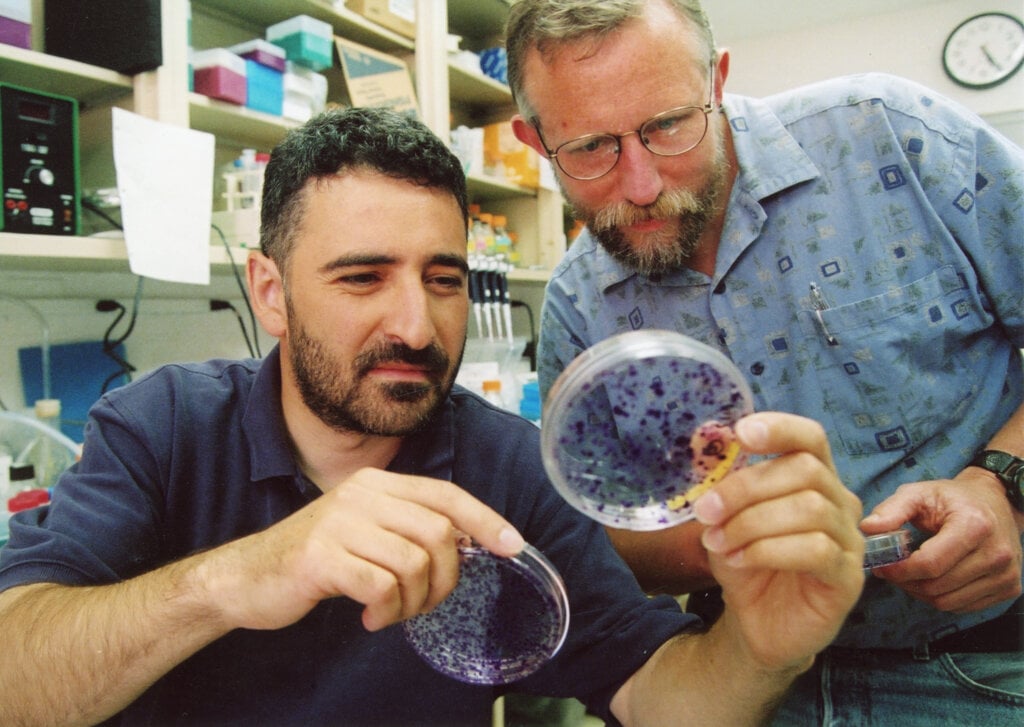

Charlie Rice (right) in the laboratory with a student.

Photo: The Rockefeller University

Were there any defining moments that influenced your career?

There were really just a series of experiences. One of them was just a really talented teacher of an introductory biology class, Dennis Barrett, who just really was a great teacher and got the class motivated and got people interacting with each other to sort of discuss different aspects of concepts that he was trying to get across. I think that connection really sort of changed my life in a sense because we actually became pretty good friends and I did some research as an undergraduate with him.

Then he actually sort of guided me towards going to the Marine biology laboratory in Massachusetts. This was a summer program for very young science learning (sort of) trainees. I did this in between my junior and senior year. It was just an amazing experience because it was basically several months in the summer where you’re just doing nothing but listening to the scientists, that are hanging out in Woods Hole (which is a nice place to spend the summer) and sort of listening to lectures, spending a lot of time in the lab, just experiencing different kinds of research techniques ranging from biophysical things to immunology and other stuff. It was a life changing experience, but I still wasn’t a hundred percent sure that I wanted to do research when I graduated from college. So I kind of wandered in central and South America because I was also growing up in California. You get exposed to a lot Spanish speaking people so I was kind of a Spanish literature minor in college. I decided to just take some time off and I applied to graduate school and then basically took off on the road and became a vagabond for the better part of a year, and then ended up returning to go to graduate school.

Were there more reasons for why you became a scientist?

It was really those experiences in college I think that got me hooked on research and then the experience of actually doing a PhD at a fantastic institution with a great group of peers and role models at Caltech. I was hooked and that was another random occurrence in the sense that I was really interested in fundamental sort of developmental biology, what happens when an egg gets fertilised and sort of early events in embryogenesis. Then I ended up, when I arrived at Caltech, getting placed in a biology lab instead of a developmental biology lab. And that was that. I enjoyed it and just sort of kept working on viruses from that time on and throughout my career.

How do you deal with failure?

Well, I don’t know. It sort of depends on how you view failure, because I guess there are different degrees of failure. I mean, one is that you sort of designed an experiment and then you just screwed it up. There was some sort of technical glitch or whatever that makes the results uninterpretable and if you can identify that and troubleshoot and then get the experiment back on track so that you get an answer that you can believe in – that’s part of the scientific process. But even when an experiment works, you have probably an idea as to what the expected outcome is going to be. If it’s a hypothesis driven experiment and the results don’t often support your hypothesis so you may end up with a well-executed experiment, really nice data and it’s just unexpected and you don’t know how to explain those results.

I guess there are two sorts of mentalities when you’re sort of confronted with that situation. One is, ‘Oh, these results don’t fit my hypothesis, I’m going to just give up.’ The other mentality is, ‘Well, this is a well-executed experiment, I’ve got the right controls. It’s giving me an answer that I didn’t expect.’ And that is, I think, the greatest opportunity in science – to actually view a result and you can either view it as failure or something unexpected and an opportunity. I think that the results of an initial experiment are usually not the end of the sort of investigation there, they’re more of the beginning. So maybe [failure] is a matter of semantics in a way and a matter of perception.

What advice do you usually give to young researchers?

I think to really make an advance is hard work. I think to be a successful scientist, you almost have to deal with our vocation as not a job as it’s more of a hobby and that we’re fortunately allowed to continue at least to some extent, depending upon what the funding agencies will let us get away with. So I think you have to have a passion for what you’re doing, so that some of these results they could be discouraging now, you just take them as a matter of course and move on. I think it’s hard work, but if it’s work for you, then you should probably do something else.

I think the successful scientists are really doing it because they’re curious and they’re doing this because there’s nothing else we’d rather be doing. I guess we sometimes get called workaholics or things like that. I would say maybe we’re more hobbyholics in the sense that we have been fortunate enough to have what we get paid to do as our hobby. I think that’s, to me, the sort of guiding principle for young scientists. You want to try and find something that you have a passion for, and then really just sort of follow that.

Do you have a lot of pets?

I am a dog fan. I’m an only child, so I didn’t have brothers and sisters but I had a continuous series of dogs from the time that I was a little boy. One of the pictures that I still have is something that my parents had taken with me when I was, I think, three years old and a basket with a bunch of puppies.

Today we have two dogs. We have a fairly dog-friendly campus here so the students that live on campus can have dogs and the sort of housing that we have right next to campus is pet friendly. My dogs sometimes come in here to the office.

Charles M. Rice with dogs.

Photo: The Rockefeller University

What do you like to do in your spare time?

I like the outdoors. We try and get away to a hideaway and a mountain range in Wyoming. We drive out there with the dogs. It’s about a 31 hour track to get to this spot. But it’s about as different as you can imagine from Manhattan. A log cabin that is, 15 miles away from the nearest paved road that’s completely surrounded by undeveloped land that is controlled by the forest service. The dogs of course love this. The only thing we have to contend with is that it does sort of overlap with some cattle grazing rights so that some of the folks that raise cattle allow them to graze in this area. That can create some issues with the dogs who sometimes take an interest in these cows when they’re not supposed to.

How did you receive the news about your Nobel Prize?

It was a phone call from the committee secretary. I was by myself here in New York and the call came on a landline at 4:30 in the morning. I was completely asleep. I couldn’t imagine who would be calling me at 4:30 and I got up to sort of go out there and pick it up and yell at whoever was calling me. Then I thought, ‘Oh, it’s just gotta be somebody that hit the wrong number or whatever.’ So I turned around to go back to bed and it stopped ringing and then it started again, and then I kind of stormed into the living room and it was pitch black and I grabbed the phone, which didn’t have a lit dial.

I don’t use this phone very often. I knew there was a connect button and a disconnect button, but I didn’t really know which one I was pushing, but I guess it was the connect button. As a consequence of that the secretary came on the phone and there was this voice with a sort of Swedish accent and it still just really didn’t dawn on me until he said more about the fact that this had to do with hepatitis C and Nobel Prize and Harvey Alter and Michael Houghton. And I thought, ‘Oh, this is beginning to sound like it might be real.’ It was quite an awakening. After something like that, you don’t go back to sleep.

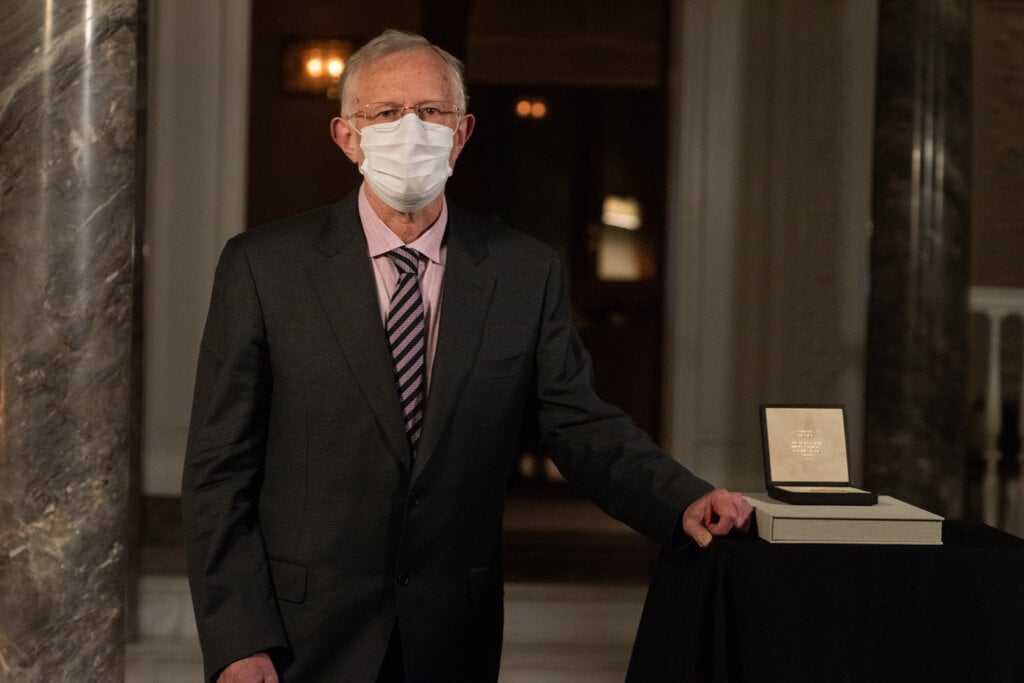

The Nobel Prize medal and diploma were presented to medicine laureate Charles M. Rice at the Residence of the Swedish Consul General in New York, USA, on 8 December 2020.

© Nobel Prize Outreach. Photo: Florence Montmare

First published: March 2021

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.