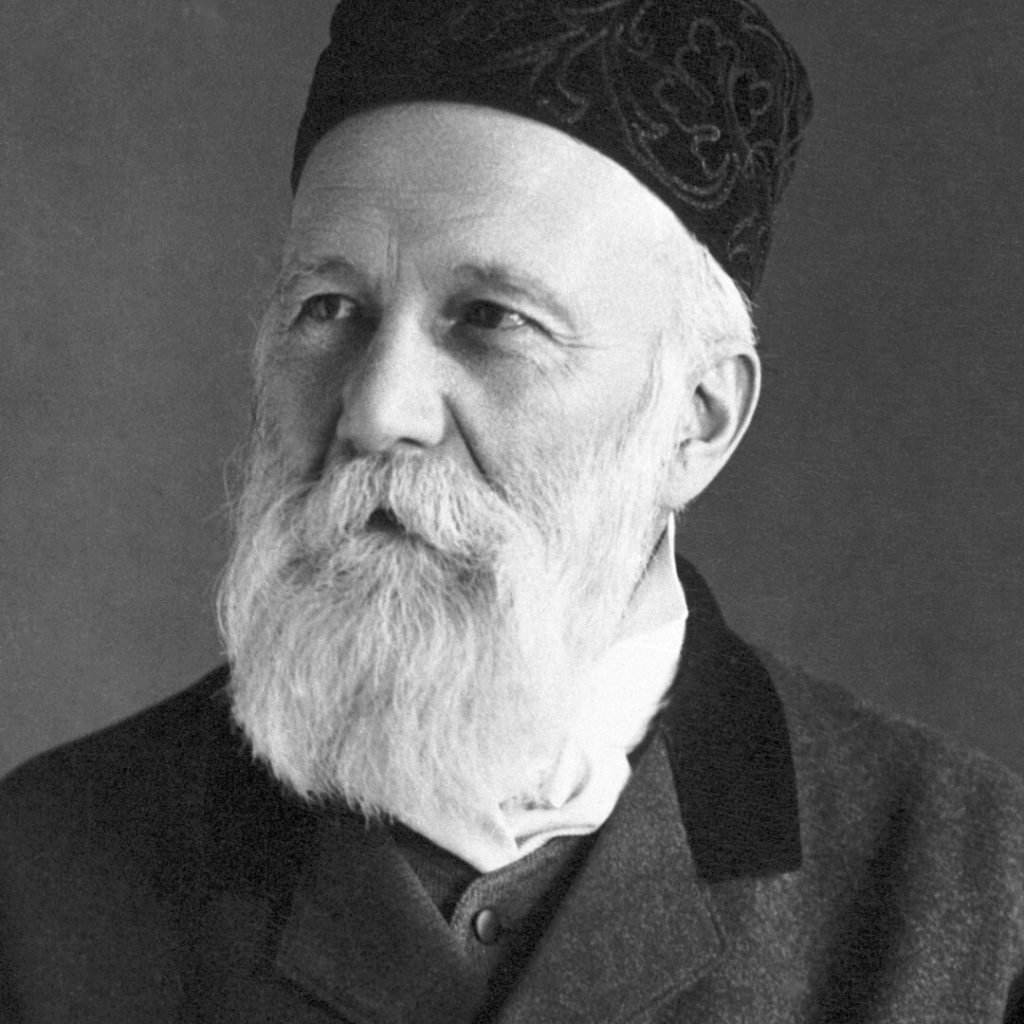

Henry Dunant

Speed read

Henry Dunant was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his humanitarian efforts to help wounded soldiers. He shared the prize with Frédéric Passy.

Full name: Jean Henry Dunant

Born: 8 May 1828 in Geneva, Switzerland

Died: 30 October 1910 in Heiden, Switzerland

Date awarded: 10 December 1901

He created the Red Cross

In 1859, young businessman Henry Dunant witnessed the battle of Solferino in Northern Italy. He mobilised the local population and set up primitive infirmaries. Upon returning home he wrote A Memory of Solferino. In it he proposed that all nations should establish organisations to help sick and wounded victims of war, regardless of nationality. Dunant’s book was sent to national leaders throughout Europe. In 1863, the International Committee of the Red Cross was founded, with Henry Dunant as its secretary. Its emblem was a red cross on a white background. A year later, an international congress approved the first Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field. When awarding the initial peace prize in 1901, the Norwegian Nobel Committee recognised the humanitarian contribution of the Red Cross, and therefore chose to honour Henry Dunant.

"The Red Cross societies were the first sign of a brotherly rapprochement in the sphere of charity. The Red Cross and the Geneva Conventions have paved the way for other great deeds."

Henry Dunant, 1899. Comment to the Tzar’s proposal regarding a conference in the Hague. Cited from Martin Gumpert, Dunant and the Red Cross, Stockholm, 1939.

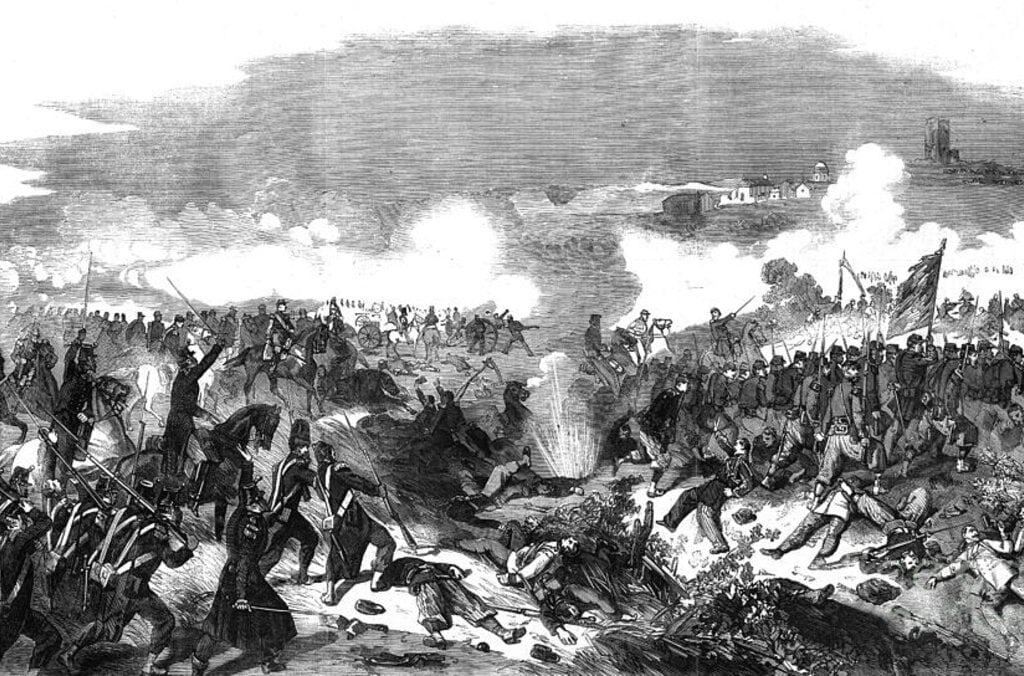

The battle of Solferino

On 24 June 1859, two armies clashed in the village of Solferino, Northern Italy, in the first stage of the unification of Italy. Backed by the army of Emperor Napoleon III of France, the kingdom of Sardinia faced Austria-Hungary. When the fighting subsided, more than 30,000 soldiers had lost their lives and thousands more were wounded. Dunant described the atrocities of the battle in A Memory of Solferino: “Another man, his cranium split wide open, collapsed dying, his brain spilling out onto the church floor … Shielding him in his death throes, I covered his poor head, which was still faintly moving, with a handkerchief.”

Scandal and vindication

The success of the Red Cross made Dunant famous, but renown was soon followed by personal tragedy. A financial venture bankrupted him, adversely affecting other members of Genevan society as well. Dunant fell from grace, resigning as Secretary of the Red Cross and leaving the city, never to return. Penniless and alone, he spent the next decades in obscurity. His final residence was a hospice in the Swiss town of Heiden. However, Dunant was rediscovered by a journalist who published an article about him. In his remaining years, he was awarded several honours, the greatest of which was the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

"My goal is to portray Dunant as a man of ideas and action, who has succeeded in bringing world culture a giant step forward."

Hans Daae, Henry Dunant, A Cultural-historical Account, 1899

A justly-deserved award?

Not everyone was pleased that the peace prize was awarded to Henry Dunant. Some felt that the Norwegian Nobel Committee had wrongly interpreted the intention of Alfred Nobel’s will. Dunant had sought to help wounded soldiers, and thus to make war more humane and less dangerous. One critic asserted that improving the conduct of war was like adjusting the temperature before boiling someone in oil! Others supported the committee’s decision. They emphasised that Alfred Nobel’s will had specified efforts to promote “fraternity between nations” as a criterion for the peace prize, and maintained that Dunant’s activities fully satisfied this criterion.

“Bury me like a dog”

Thus wrote Henry Dunant in his last will and testament, and his wish was granted. He was laid to rest without a eulogy at the Sihlfelder cemetery in Zurich, Switzerland. An old man, he continued to live frugally at the hospice after he received the peace prize. He bequeathed his prize money to humanitarian organisations in Switzerland and Norway. The Norwegian Red Cross and the Norwegian Women’s Public Health Association each received NOK 15,000, a substantial sum at that time.

Learn more

Jean Henry Dunant‘s life is a study in contrasts. He was born into a wealthy home but died in a hospice ...

Read more about the work of Henry Dunant and the founding of the Red Cross.

Disclaimer: Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organisations and individuals with regard to the supply of photographs. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.