Fridtjof Nansen

Article

Fridtjof Nansen: Scientist and humanitarian

by Asle Sveen*

This article was published on 15 March 2001.

In the summer of 1922, the last of the German and Austria-Hungarian soldiers who had been in Russian captivity after the First World War were shipped home across the Baltic. On the return voyage, the ships carried the last Russian prisoners-of-war from Germany. Altogether, over 400,000 prisoners were exchanged in less than two years. The credit for this was given mainly to the Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen. That autumn he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Nansen did his country great service as a politician and diplomat, but he acquired his international renown primarily as a scientist, polar exploration hero, and the altruistic champion of people in times of distress.

Well off, intelligent and sporty

Fridtjof Nansen was born in Kristiania (as Oslo was then known) in 1861.1 His father was a pious lawyer, and his mother belonged to one of the few aristocratic families in Norway, at the time a poor country.2 The family was relatively well off. Fridtjof was sent to a private school, where he distinguished himself in all subjects from classical languages to mathematics and sports.

In the 1870s, skiing was rapidly gaining in popularity among Kristiania’s upper class. Both Fridtjof’s parents were enthusiastic about the sport, and encouraged their son to participate, which he did, with great success. The picture shows Fridtjof Nansen skiing in Lysaker.

In 1880 he took the university matriculation examination and began to read zoology at the only Norwegian university, in Kristiania. He proved himself to be outstanding in both knowledge and industriousness, so the university sent him to the Arctic on a sealing vessel to take samples of marine life. It was on the four-month expedition in the waters off Greenland that Nansen first acquired his taste for the polar regions. He did such good work that he obtained an attractive research post at Bergen Museum. The old Hanseatic town of Bergen was the only town in Norway with a continental atmosphere. For want of a university, some of its prosperous citizens had instead set up an independent research centre. In Bergen young Nansen came into contact with internationally-minded scientists, including Armauer Hansen, discoverer of the leprosy bacillus. The scientists in Bergen were enthusiastic adherents of Darwin’s new theory of evolution, and Nansen soon became a convinced Darwinist – a fact he kept from his strictly religious father.

Science and adventure

Nansen threw himself into the study of the invertebrate nervous system. One of Darwin’s main points had been that all living organisms were related. Nansen accordingly believed that by studying the relatively simple nervous system of the hagfish, he could arrive at some of the principles underlying the working of the human central nervous system and brain.

Fridtjof Nansen with a microscope at Bergen Museum, 1887.

Nansen enjoyed his work in Bergen, but disliked the snowless west coast winters. In the winter of 1884, he attracted nationwide attention by skiing across the mountains from Bergen to Kristiania to take part in ski jumping and cross-country skiing competitions.

Nansen was aiming for a doctorate in zoology and used a travel grant to visit Germany, Switzerland, and Italy, where he met recognised scholars in his field. But the polar regions were calling, and while working on his doctorate, he was also planning to become the first person to cross Greenland on skis. He was sponsored by a wealthy Danish businessman, and in 1888 he completed the strenuous journey in the company of three Norwegians and two Sami.

This made Nansen a national and international celebrity in one stroke. In Kristiania the Greenland-farers were greeted by bands, artillery salutes, and a cheering crowd of 50,000 people. Norway was the junior partner in the union with Sweden, and people were hungry for national heroes of their own. Nansen received invitations to lecture at The Royal Geographical Society in London and in several other European capitals. A book on the Greenland expedition, published in several languages with Nansen’s own photographs and drawings, placed him on a sound financial footing.

A contributor to Norwegian national pride

He had obtained his doctorate four days before leaving for Greenland, and in the autumn of 1889 he married the singer Eva Sars.3 Among the reasons why he fell for her was that she was a good skier and enjoyed outdoor activities.

Despite his secure position as an internationally recognised scientist and explorer, Nansen could not settle down. He had set himself the target of reaching the North Pole, planning to use a ship which could drift with the ocean currents, crossing the Pole from east to west. His plan won the support of the Norwegian government. Norwegian nationalism was reaching fever pitch, and to obtain a higher profile in the union with Sweden the country needed all the international prestige it could get.

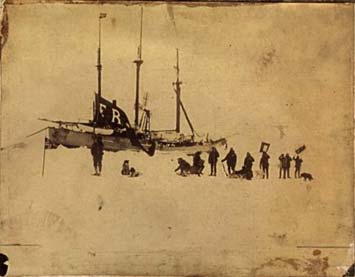

National expansion in the cold. Members of Nansen’s “Fram” expedition to the North Pole celebrate Constitution Day with flags and banners on May 17, 1894.

Nansen had the polar vessel “Fram” built.4 It was designed so as to prevent the ice from pressing it down. In 1893, Nansen allowed the “Fram” to be frozen into the drift ice north of Siberia in the hope that it would drift over or close to the North Pole. However, it soon became evident that the ship was drifting too far south. With one companion, Hjalmar Johansen, Nansen left the “Fram” and the rest of the crew, and set off to ski to the North Pole. They got further north than anyone had been before, but drifting ice and lack of food forced them to turn back and seek the mainland. They survived two winters by shooting walruses and polar bears. By an incredible stroke of luck, they stumbled across a British expedition, headed by Frederick George Jackson, on Frans Josefs Land, which took them back to Norway. The “Fram” also reached home safely with its whole crew intact. Although the North Pole had not been reached, Nansen was celebrated as a polar hero to an even greater extent than before, both nationally and internationally. In Kristiania he was received at the palace by King Oscar, and on the palace balcony accepted the plaudits of the enormous crowd assembled outside.

When “Fram” returned to the Norwegian capital on September 9, 1896, she was met by more than a hundred vessels in the Oslo fjord. A few days later, thousands of people gathered in a popular feast to honor Nansen and his crew.

Diplomat of a new independent nation

During the period of Nansen’s absence, relations between Norway and Sweden had approached a crisis. The two countries were formally equal, but the King was Swedish-born, and Sweden managed the foreign affairs of both countries. More and more people in Norway were inclined to break out of the union with Sweden. Nansen agreed and exploited his international fame to plead Norway’s cause abroad, especially in Britain.

When the break came in 1905, Nansen strongly opposed the most ardent nationalists, who were urging war unless Sweden accepted all of Norway’s demands. He was also in favour of a monarchy, and the Norwegian government sent him to persuade Denmark’s Prince Carl to become King of Norway, taking the old Norwegian royal name of Haakon. As he was married to England’s Princess Maud, this would ensure important foreign policy links to Britain. The new Norway based its foreign policy to a large extent on the protection of the British Royal Navy. Nansen became Norway’s first ambassador to Great Britain, where he became a personal friend of the British Royal Family.

Fridtjof Nansen in uniform when he served as Norwegian Ambassador in London.

In 1907, Nansen tragically lost his wife, which left him a widower with five children. Relations with Eva had been troubled, both because he was away so often on expeditions, lecture tours, or official business, and because he attracted many women.

Nansen’s hopes of being the first to reach both the North and the South Pole were crushed by Robert Peary in 1909 and Roald Amundsen in 1911. He therefore decided to devote more attention to his scientific career. But the outbreak of the World War in 1914 drove him back into politics. Neutral Norway was dependent on imports of cereals and other supplies, and Germany’s unlimited submarine war hit the country very hard. In 1917, Nansen was sent to the United States to seek supplies for Norway. The negotiations were protracted because the United States wanted to pressure Norway into joining the war on the Allied side. While there, Nansen became acquainted with President Wilson’s “Fourteen Points” for peace, and when he returned to Norway he became chairman of the Norwegian League of Nations Association. In that capacity, he attended the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919.

A humanitarian from a small, neutral country

While the peace negotiations were going on at Versailles, the civil war between Reds and Whites was raging in Russia. It resulted in famine and American politicians wanted to exploit food aid as a means of winning concessions from Lenin’s regime. One American claim was for the release of all Americans in Soviet captivity in return for food aid. They sought Nansen’s help as an intermediary in the negotiations with the Bolsheviks. Nansen was not unwilling, but the plan was abandoned when the civil war ended in a victory for the Reds.

Russia was still holding 250,000 prisoners-of-war from the First World War, Germans as well as people of many other nationalities from the dissolved Austria-Hungary. An estimated 200,000 Russians were prisoners on the German side. In the spring of 1920, the League of Nations appointed Nansen as High Commissioner in charge of arrangements for exchanges of prisoners. The appointment came about thanks to the efforts of Philip Noel-Baker, a young British member of the League of Nations leadership. Noel-Baker was eager to boost the League’s reputation after the American Senate had rejected US membership. The League needed to be able to point to concrete results, which Noel-Baker believed Nansen would be able to deliver.

To some extent, the ground had already been prepared. The Red Cross had taken up the cause, and Russia had released the prisoners. The problems were money, and the ships to carry the prisoners home. These became Nansen’s main tasks. Thanks to his popularity in Britain, he was able to persuade the British government to grant loans to finance the exchanges of prisoners. Nansen also got the British to agree to release German ships which had been commandeered since the World War, so they could be used to transport prisoners of war across the Baltic.

950 German prisoners-of-war on board “Cyprus” arrive in Szczecin on July 26, 1921, after having crossed the sea from Riga.

While waiting to be shipped out, the eastern prisoners needed food and clothes. The Communist leaders were suspicious of the Western governments which had supported the Whites in the civil war and refused to negotiate with anyone other than Nansen. From an office in Berlin, known as Nansen Aid,5 Nansen arranged for supplies of food, clothes and medicines for the prisoners on Soviet territory.

While this help was being provided, a period of famine began in the Soviet Union. In the summer of 1921, the author Maxim Gorky appealed for international aid. An American aid organization headed by Herbert Hoover negotiated an agreement with the Russians. They would obtain food aid in return for releasing American prisoners and using their gold reserves to buy grain in the USA.

Lenin saw Nansen and the League of Nations as a possible counterweight to the United States. At the request of Gorky and the League, Nansen went to the Soviet Union, where he was taken to the famine-stricken areas. But his appeal for help was met with scepticism on the part of western governments. The British in particular, now viewed Nansen as Lenin’s naive tool. They were afraid food aid would strengthen the Communist regime. Nansen argued that an economic boycott of the Soviet Union, in addition to increasing the suffering of the starving people, would also be an obstacle to trade between Russia and the rest of Europe and that without such trade, European postwar reconstruction would be impeded.

These views won no support among the western governments, so Nansen was obliged to rely on private charity. The help he was able to provide was therefore modest compared to America’s. To help him with its organization, he had a young Russian-speaking Norwegian, Vidkun Quisling.6 (Ten years after Nansen’s death, Quisling’s name was to become synonymous with traitor when he supported the German occupation of Norway.)

In the summer of 1922, Nansen was able to report to the League of Nations that the repatriation of over 400,000 prisoners of war had been completed. At the same time, he thanked the International Red Cross, which had carried out the bulk of the practical work.

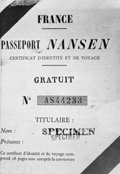

The Red Cross had also made Nansen’s name known in a different connection. Lenin deprived the thousands of Russians who had fled to the West after the civil war of their nationality. Statelessness prevented them from crossing borders. The Red Cross proposed using Nansen’s name on a special passport for refugees. The League of Nations approved the idea in 1922, at the same time appointing Nansen as its first High Commissioner for Refugees. The Nansen passport became very sought-after, and enabled such Russian artists as Igor Stravinsky, Sergey Rachmaninov, Marc Chagall and Anna Pavlova to begin new lives in the West.

A proof-print of the “Nansen Passport” published in France.

The nomination for the Nobel Peace Prize

It was thus hardly a surprise when Nansen was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize the same autumn. The nominators included Professor Fredrik Stang,7 a member of the Nobel Committee, and the Danish group of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. They emphasised his work for the repatriation of prisoners-of-war, his efforts for the starving in Russia, and his ability to “appeal to world opinion with brotherly love as the driving and animating force”.

The adviser, Frede Castberg, who reported on Nansen’s candidacy, discussed the disagreement between Nansen and the Western governments about help to Russia. He defended Nansen’s position and concluded that Nansen had a strong influence on the work of the League of Nations because of “the high esteem in which Nansen’s personality is held, and the energy and wisdom with which he has stood up for his own proposals and that of his government in the Council of the League of Nations”.

In a private letter to a friend, Nansen wrote: “It is truly so strange to me and beyond my comprehension how all this business of the Peace Prize has come about; for it was really entirely by chance that I was driven to take up this work, which was not mine”. No doubt he was thinking among other things of Philip Noel-Baker’s initiative in persuading him to work for the League of Nations; he wrote to him concerning the Peace Prize that “If our work is worthy of it, you would have deserved it much more”.8

In the thorough biography of Nansen he published in 1996, Roland Huntford concluded that “Nansen is among the few really worthy winners of the Peace Prize, although he is probably the one who spent the shortest time earning it”.

Nansen spent the Peace Prize money in Russia, or the Soviet Union as the country was called from 1922 on. He had two model farms established for the development of new agricultural methods, one in the Ukraine and one by the Volga. Among the things they received were the first tractors in Soviet agriculture.

Nansen was made an honorary member of the Moscow Soviet, and many felt that he had become an uncritical “Russia worshipper”. In his book Russland og freden (Russia and Peace), he defended Lenin’s harsh methods and argued that they were necessary in order to build up the country.

“Ethnic separation” – a humanitarian solution?

After the award, Nansen continued to devote all his energy to work for the League of Nations. The League asked him to resolve a complicated dispute which had arisen between Greece and Turkey. Turkey had been one of the losing parties in World War I, and the state was breaking up. Greece tried to profit from the situation by taking the west coast of Asia Minor, where a large proportion of the population was Greek. But Turkey’s new leader, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk,9 drove the Greeks out in 1922, in consequence of which over one million ethnic Greeks fled from Asia Minor to Greece. In the opposite direction, Turks fled from Greek-controlled territories.

Nansen decided that the only solution lay in “ethnic separation”. Turks and Greeks could not live together. He persuaded the Greek and Turkish governments to agree to a population exchange. Moslems in Greek areas would be exchanged with Greek-Orthodox groups in Asia Minor. The exchange was completed in 1924.

Nansen’s last years

The following year, influential circles tried to draw Nansen into Norwegian politics. Urged by the fear of Communism, Norwegian conservatives were looking for a strong leader.10 Although Nansen believed that Communism was necessary in a backward country like Russia, he was against Communism in the Norwegian context, because it ran counter to individualism. Nansen thought Communism was ridiculous in a developed country with universal suffrage. He shared with many others the ideas derived from social Darwinism that people needed to be led by their strongest and most skilful leaders. He was not a warm supporter of political parties or parliamentary democracy.

However, although Nansen lent his name to the efforts the conservatives were directing against Communism and Socialism in Norway, he refused to run for Prime Minister.

Instead, he strove to obtain a home on the Soviet side of the border for Armenian refugees from Turkey. The Allies had called on the Armenians to revolt against the Turks during the World War, which resulted for them in a tragedy of massacres and persecution.

In 1925, on the request of the International Labour Organization and the League of Nations, Nansen visited Armenia with a group of experts to consider possibilities of cultivating desert areas and thereby facilitating resettlement of Armenian refugees. In the picture, Nansen tastes the food at a summer camp for Armenian orphans outside Alexandropol.

His work in the Armenian cause sapped much of Nansen’s strength in the late 1920s,11 but it did not stop him from planning another polar expedition. He was busily engaged in making arrangements for an airship flight across the Arctic when he died suddenly of a heart attack in May 1930, half a year before his 70th birthday.

Nansen was given a state funeral. A vast crowd followed the funeral procession when he was interred on Norway’s Independence Day, the 17th of May.

Bibliographical notes

1. The biographical data have been mainly taken from Roland Huntford: Fridtjof Nansen. Mennesket bak myten (The Man behind the Myth), Aschehoug 1996; the adviser’s report by Professor Frede Castberg in Redegjørelser (Reports) 1922 NNK (the Norwegian Nobel Committee); Irwin Abrams: The Nobel Prize Winners and the Laureates, G.K. Hall & Co 1988; and Der Friedens – Nobelpreis 1917 bis 1925, Edition Pacis Switzerland 1989.

2. Nansen’s father, Baldur Frithjof Nansen, was of Danish stock on both his mother’s and his father’s side. The most prominent member of the Nansen family was Hans Nansen, mayor of Copenhagen in the 1600s. He engaged in exploration in arctic Russia and trade in Iceland. Nansen’s mother, Adelaide Johanne Thekla Isodore, was born Wedel Jarlsberg.

3. Eva Helene Sars (1858-1907) married Nansen in 1889. Her brothers were the historian Ernst Sars and the zoologist and oceanographer Ossian Sars. Ernst Sars was to have considerable influence on Nansen. As a member of the so-called “Lysaker circle” of scientists and artists, Nansen figured prominently in the build-up of Norwegian nationhood leading to the dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905.

4. Nansen’s ship “Fram” was built by Colin Archer (1832-1921) from Larvik in 1891-92. Otto Sverdrup and Roald Amundsen also sailed in the “Fram” on polar and exploration voyages. In 1936, the “Fram” was housed in its own museum building in Oslo.

5. Nansen Aid grew into an organization that continued to operate after his death in 1930. The Nansen Office was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1938.

6. Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (1887-1945), Norway’s best Military Academy graduate, was the Norwegian military attaché in Petrograd in 1918. He served as Nansen’s secretary from 1922 to 1926 during his work in the Soviet Union.

7. The letter of nomination from Stang was also signed by Professor Edvard Bull and Director General Stuevold-Hansen. Later the same year, on October 2, 1922, Stang was elected Chairman of the Nobel Committee.

8. Quoted from Huntford, p. 537. According to Halvdan Koht’s diary (the Norwegian Nobel Committee) there was no discussion in the Nobel Committee concerning Nansen’s candidacy. All he has on record concerning the meeting on December 1, 1922 is that “Nansen had sent a wire to say that he was afraid it would be resented if a Norwegian got the prize again this year (Lange had been awarded the previous year together with Branting), and that he thought Robert Cecil should have been awarded first.”

9. Mustafa Kemal (Ataturk) (1881-1938) was the Turk commander who obtained heroic stature by resisting the Allies at Gallipoli. In 1922, the last Sultan was deposed, and in 1923 Turkey became a republic with Kemal as President. He used harsh methods to force through the westernisation of the country. In 1934 he was named “Ataturk” – father of the Turks.

10. The conservative, strongly nationalistic and anti-communist Fedrelandslaget (Fatherland Association) was founded in 1925. Nansen was the main speaker at the inaugural meeting. Christian Michelsen, a former prime minister, was among those who hoped to find in Nansen a strong leader who could bridge the gaps between the non-socialist parties. Fedrelandslaget was to reach a total membership of nearly 100,000.

11. In his Minne frå unge år (Recollections from Early Years), Aschehoug 1968, member of the Nobel Committee Halvdan Koht writes on pp. 286-90 of his impression that Nansen had felt torn between his desire to pursue a scientific career and the need to help the Armenians. “In the end it was his sense of duty towards suffering people which won, and he took the task upon himself. But it cost him a great deal.” (p. 290).

Acknowledgements

The article was translated from Norwegian to English by Peter Bilton.

All pictures courtesy of Norges Nasjonalbibliotek avdeling Oslo, Billedsamlingen, Fridtjof Nansen Archive.

* Asle Sveen (1945 -) obtained his Master in History at the University of Oslo in 1972. He has more than twenty years of experience as teacher in history, social sciences and Nordic languages in senior secondary schools in Norway. Since 1983 he has written textbooks in history and social sciences for junior and senior secondary levels in the Norwegian school system. Asle Sveen is also author of four historical novels for young people, and he has been a researcher both at the Institute for Teaching and School Development, University of Oslo and at the Norwegian Nobel Institute. He is currently working with two other Norwegian historians on the history of the Peace Prize. The book will be published in August 2001.

First published 15 March 2001

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.