Ralph Bunche

Article

Ralph Bunche: UN Mediator in the Middle East, 1948-1949

by Asle Sveen*

This article was published on 9 December 2006.

“I have a bias in favour of both Arabs and Jews in the sense that I believe that both are good, honourable and essentially peace-loving peoples, and are therefore as capable of making peace as of waging war …” – Ralph Bunche, 19491

Nobel Peace Prize Laureate

In 1950 the Norwegian Nobel Committee awarded the Nobel Peace Prize to the first non-white person, the African-American and United Nations (UN) official Ralph Bunche. He received the Peace Prize for his efforts as mediator between Arabs and Jews in the Israeli-Arab war in 1948-1949. These efforts resulted in armistice agreements between the new state of Israel and four of its Arab neighbours: Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

Two members of the Norwegian parliament nominated Ralph Bunche for the Nobel Peace Prize. Both had connections to the newly founded United Nations. One was Norway’s first UN ambassador, and the other was a member of the Norwegian UN delegation. The nomination stated: “Although it can not be said to be Dr. Bunche’s merit, but the development process itself that made the parties end the hostilities, there can be no doubt that it is Dr. Bunche’s merit that the challenging negotiations over a ceasefire were brought to a positive result in a relatively short time”.

The nominators had several motives. Awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Bunche “would thereby not only honour him personally, but express trust and faith in the ability of the United Nations to solve international disputes by way of mediation between the parties”. Furthermore, the nominators could not “neglect to mention that giving the Nobel Peace Prize to a member of the coloured race is a boost to peace in itself”. Thus the Peace Prize was meant to strengthen the UN and to serve as an initiative against racism as well as to honour Ralph Bunche.

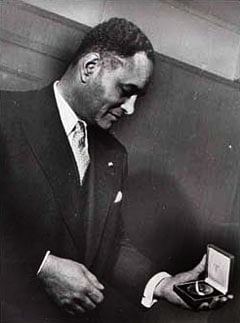

Ralph Bunche studying his Nobel Peace Prize medal after receiving it in Oslo, Norway on 10 December 1950.

Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, City University of New York, Graduate Center

Family Background and Education

Ralph Bunche was born in 1903, in the industrial city of Detroit, Michigan, in the United States. Most of his ancestors were descendants of black slaves, but there was also Irish heritage in his family. After his mother’s death in 1917, Bunche moved with his grandmother to Los Angeles, California. She was a light-skinned woman who could almost pass for white, but she was proud of her black origin and raised Ralph to be proud of his race, work hard and get the best education he could.

It was in Los Angeles that Bunche had his first real encounter with racial discrimination. Although an excellent high-school student, he was excluded from the most popular students’ association. Nevertheless, he wrote for the campus newspaper, was president of the debating team and became a star basketball player. In 1927 he graduated from the University of Los Angeles (UCLA) as a Political Science major and valedictorian of his class.

Earning a master’s degree at Harvard University, Ralph Bunche took a teaching position at Howard University in Washington, where he founded the school’s Political Science Department.

Ralph Bunche obtained a doctorate in French Colonial Policy as the first African-American to earn a doctorate in Political Science. He lived and studied for several months in different parts of Africa, and was appalled by the striking poverty he observed and the bad treatment of Africans by the colonial administrations. His studies extended to include the rights of all peoples without self-government, and he developed a profound knowledge of trusteeships and the question of decolonisation.

Struggle Against Racism

In the 1930s Bunche became a recognized authority on race relations, and for a while was attracted to Marxist analyses that emphasised economic explanations for poverty and racism. He was one of the founders of the radical National Negro Congress, which had the aim of cooperation on social issues and the creation of mutual solidarity across the colour bar.

In 1939 Bunche joined the staff of the Swedish social scientist Gunnar Myrdal, who studied American racial segregation. Myrdal disagreed with the Marxist theory that black Americans could only obtain liberation and equality through class struggle in cooperation with the white working class. In contrast, he believed that a large part of the white population was so infused with racism that the strategy of the African-Americans ought to be to get the federal government to practise the spirit and principles of freedom embodied in the Constitution of the United States for the whole American populace. Bunche was strongly influenced by Myrdal, and in 1940 he left the National Negro Congress after it had been taken over by the American Communist Party.

United States Official

In December 1941, the United States was brought into the Second World War by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Shortly before this dramatic event, Bunche joined the staff of the American intelligence service as an expert on colonial areas. His job was to provide the American forces with useful information for operations in Africa and Asia. Through hard work and excellent memorandums Bunche was soon moved to positions of higher responsibility, and in 1944 he became the first African-American to hold a top position in the US State Department, with responsibility for colonial issues.

Assistant to the Special Committee on Palestine

In 1945 the Second World War was brought to an end and the United Nations was founded. The first UN Secretary-General, the Norwegian Trygve Lie, asked Bunche to join the UN. Bunche went into the UN service the following year to work with the question on decolonisation. In 1947 Lie made him assistant to a special committee on Palestine.

During this time, a conflict was brewing in the Middle East between the British, Jews and Arabs over Jewish demands for a separate state. At a special session of the UN in May 1947, Jewish delegates argued that European anti-Semitism and the Nazi extermination of six million Jews during the Second World War made the creation of a Jewish state absolutely necessary. An Arab representative countered that the Arabs of Palestine should not suffer for the crimes of Hitler.2 Finally, Britain left the UN in charge of the Middle East conflict, which was marked by increasing bitterness and extremism, and a UN Committee was formed to find solutions to the problems.

The committee travelled for six weeks, conducting interviews in Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, as well as visiting Jews in displaced-person camps in Europe. Many Arabs refused to talk to the committee, claiming that the UN had no right to give away any part of their land. The most extremist Jews wanted to take all of Palestine as well as areas on the east bank of Jordan, while the moderates were prepared to accept a partition of Jewish and Arab territories.

Bunche did not find it easy to work with the members of the UN Committee, which he characterised as the worst group he had ever worked with because of internal strife and disagreements. Finally, the majority of the UN Committee proposed a partition of Palestine into two independent Jewish and Palestinian states. Jerusalem was to be governed by the UN to guarantee access for Jews, Christians and Muslims to all their holy sites. The minority in the committee wanted a federal state, with separate provinces for Arabs and Jews, and with Jerusalem as a common capital. Although Ralph Bunche had drafted both proposals, he was frustrated. In a letter to his wife, he wrote that the Palestine problem was the intractable sort that had no possible satisfactory solutions.

In the autumn of 1947, a majority in the UN, including the United States and the Soviet Union, adopted the partition plan. The Arab and Muslim delegations marched out in protest, while Jews worldwide jubilantly hailed the result.

Assistant to Count Folke Bernadotte

On 14 May 1948, the last British ship sailed from Palestine. Jews celebrated the creation of the state of Israel, but soon after Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Saudi Arabia declared war on the new state. The Israeli army, which was better trained and equipped than its opponents, soon had the upper hand in the war, conquering land beyond the areas allotted to them in the UN partition plan. The war made Arab families flee parts of Palestine occupied by Jewish forces, and during the fighting as many as 700,000 Palestinians fled their homes, creating a large-scale refugee problem.

The Security Council appointed the Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte as mediator to promote a peaceful adjustment of the situation in Palestine. As the head of the Swedish Red Cross, Count Bernadotte had successfully negotiated the release of Danish and Norwegian prisoners from the Nazi concentration camps during the last weeks of World War II in Europe. Trygve Lie asked Ralph Bunche to accompany Bernadotte to the Middle East as Chief Representative of the Secretary-General. Lie saw Bunche as the man who understood the conflict and who was able to draft compromise proposals which could bring the fighting to a halt.

Bernadotte and Bunche were shuttled between Jerusalem and the Arab capitals in the Count’s white plane to put a stop to the war. In June the parties accepted a ceasefire agreement drawn up by Bunche.

Count Bernadotte moved his headquarters to the island of Rhodes to have peaceful and neutral surroundings. He believed that the partition plan needed revisions to ensure Arab acceptance. At Rhodes, Bernadotte and Bunche worked out a draft that was later known as the Bernadotte Plan. This plan proposed a union between Jordan and Palestine and the creation of an independent Israeli state. The proposal included Jerusalem in an Arab state with autonomy for the Jewish minority. In addition, Palestinian refugees should be allowed to return to their homes in Israeli-occupied territory or receive compensation for the losses of their homes.

The draft was designed for internal discussion but its content was leaked. As a result, the draft had to be published as a document of the UN Security Council. Both Palestinians and Jews rejected the plan, and the Lehi group, an extremist Jewish faction, disliked it so much that it set out to assassinate the charismatic Bernadotte before he could influence the UN. The Lehi group, which included future Israeli Prime Minister Yitzak Shamir, regarded Bernadotte as an agent of the British government, and wanted him dead.3 Bunche was scheduled to meet Bernadotte in Jerusalem, from where they would proceed to put the new partition proposal before the UN General Assembly. Several delays prevented Bunche from reaching the Jerusalem rendezvous point on time, and Bernadotte instead brought a French UN officer to accompany him to his meeting in the city that day. En route they were stopped by armed men in Israeli uniforms at the Mandelbaum gate in Jerusalem. One of them pointed his machine gun into the car and fired, killing both Bernadotte and the French officer — the latter probably wrongly taken to be Bunche. Meanwhile Bunche, who was supposed to have been in the car, arrived at the rendezvous point half an hour after the Count had left.

|

| Ralph Bunche (right) and Count Folke Bernadotte boarding a United Nations plane. Photo: Courtesy of Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies, City University of New York, Graduate Center |

Leader of the UN Palestine Mission

When news of Bernadotte’s death reached the UN, Trygve Lie immediately phoned Bunche and asked him to succeed Bernadotte and carry on the mediation effort. Despite awareness of the personal danger posed by the role, Bunche did not hesitate to accept Lie’s request. Bunche travelled to Paris, where he met with UN representatives to discuss the new borders between Jews and Arabs that he and Bernadotte had proposed.

In the meantime, fighting in Palestine broke out again between Israeli and Egyptian forces, with Israel on the offensive conquering new ground. The General Assembly of the UN gave up the Bernadotte Plan and the Security Council in a resolution originally drafted by Bunche, demanded that the parties in the conflict should establish an armistice through negotiations.

After weeks of toil, Bunche was able to bring the Israelis and Egyptians to the negotiating table on Rhodes in January 1949. The Arab countries initially refused to negotiate directly with Israel, but on the isle of Rhodes Bunche managed to persuade the Egyptians and Israelis to sit together at the negotiating table, and discuss the Middle East problems face to face.

The negotiations began with Israel and Egypt in January 1949. Through discretion, patience and humour Bunche won the confidence of the negotiating parties. He formulated compromise proposals and was willing to work for months to come to an agreement. With Bernadotte’s fate in mind, Bunche made the negotiators agree to total secrecy; the press and Security Council were only to receive official press reports. Hard negotiations led to the signing of a truce by both parties by the end of February 1949. As Egypt was the leading Arab nation, it paved the way for later agreements between Israel and Jordan, Lebanon and Syria.

An Agreement in Favour of Israel?

Recent research has shown that the UN Secretary-General Trygve Lie and the United States government played a much more decisive role in the negotiations than was otherwise known before.4 On several occasions Bunche asked President Truman and Lie for help to prevent a breakdown in the negotiations, and information that was meant solely for the UN was passed on to the United States delegation by Secretary Lie. Like most Norwegian Social Democrats, Lie sympathised strongly with the Jewish position, and President Truman supported the Jewish case because his advisers informed him that the Jewish votes in the United States were both important for his re-election in 1948 and for the Democratic Party in the future. As both Lie and Truman were biased in favour of Israel, pressure to compromise was mainly applied to the Egyptian delegation, and the final agreement was more beneficial to Israel than the Arab countries, despite Bunche’s efforts to achieve impartiality. In fact Bunche’s diary shows that he was often annoyed with the behaviour of the Jewish delegates and had sympathy for the demands of the Egyptian delegation.

With the conclusion of the agreement between Israel and Syria on 20 July 1949, the Rhodes armistice negotiations were completed – Israel was recognized by the world community as an independent state within new borders, and was admitted as a member of the UN.

Personally, Bunche believed that the Palestinian Arabs were the big losers in the conflict, and, in fact, the agreements sealed the fate of the UN’s plan for an independent Palestinian state. The Israelis kept almost all the land they had conquered. Israel had expanded from the UN-allocated 55% of British ruled Palestine to 79%. Jordan and Egypt took what was left for the Palestinian Arabs. The armistice agreements were intended as the basis for peace negotiations within a year, but these never took place. Although the UN and the United States called for the rights of the Palestinian refugees to return to their homes, this never happened. The fate of the Palestinian refugees remained an unsolved problem.

The Nobel Peace Prize

When the news came that Bunche had won the 1950 Nobel Peace Prize, he considered declining it because, in his opinion, representatives of the UN ought not to be rewarded with prizes for their work for peace. But Trygve Lie insisted that he receive the Peace Prize – the UN needed all the publicity it could get.

The choice of Bunche as Nobel Peace Prize Laureate was well received the world over. In Sweden, it was seen as an indirect tribute to Folke Bernadotte. In Norway, a newspaper wrote that the prize was a message to non-white people of the world. Only the Soviet press was dissatisfied. One article branded Bunche as an ‘Uncle Tom’ – a good-natured black who lent himself to the efforts of the American authorities to keep the non-white population down.

By the time the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Bunche, the Korean War has started, with the United Nations as a participant. In his Nobel Lecture in Oslo, Bunche stressed that the UN was the greatest peace effort in human history, but it should be allowed to build an international military force to be deployed against aggressors violating the UN Charter. He also pointed to the fact that millions of people in Africa and Asia were poor and oppressed and that the West, in order to promote democracy, must support the basic creed of the UN that all peoples must have equality and equal rights.

Later Years

Bunche continued working for the United Nations under the Secretary-Generals Dag Hammarskjöld and U Thant. In the United States he supported the growing Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, and marched and spoke together with the Nobel Peace Prize Laureate of 1964, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bunche and U Thant tried to put an end to the Vietnam War and establish lasting peace in the Middle East, but they suffered many setbacks. Bunche felt that the Six-Day War of 1967 between Israel and the Arab states ruined almost all the détente he had managed to establish in the region.

When Ralph Bunche died in 1971, the United Nations General Assembly paid its final tribute to him with one minute of silence.

Bibliography

Brian Urquhart: Ralph Bunche. An American Life. (New York, Norton, 1993).

Charles P. Henry: Ralph Bunche. Model Hero or American Other? (New York University Press, 1999).

Ingrid Næser: Right Versus Might. A Study of the Armistice Negotiations between Israel and Egypt in 1949. Dissertation in History. University of Oslo. Spring 2005.

Øivind Stenersen, Ivar Libæk, Asle Sveen: The Nobel Peace Prize. One Hundred Years for Peace. (Cappelen, Oslo, 2001).

Irwin Abrams: The Nobel Peace Prize and the Laureates. An illustrated biographical history 1901-2001. (Science History Publications/USA 2001).

Martin Gilbert: Israel. A history. (Black Swan UK 1998).

* Asle Sveen (1945 -) obtained his Master in History at the University of Oslo in 1972. He has more than twenty years of experience as teacher in history, social sciences and Nordic languages in senior secondary schools in Norway. Since 1983 he has written textbooks in history and social sciences for junior and senior secondary levels in the Norwegian school system. Asle Sveen is also author of four historical novels for young people, and he has been a researcher both at the Institute for Teaching and School Development, University of Oslo and at the Norwegian Nobel Institute. In 2001 he published “The History of the Nobel Peace Prize Through 100 Years” with two other Norwegian historians. He also worked as an adviser of the project group that developed the Nobel Peace Center in Oslo, which opened in 2005.

1. Henry, Charles P: Ralph Bunche. Model Negro or American Other? New York/London: New York University Press, 1999, p. 142.

2. Martin Gilbert: Israel. A history. p. 144. Black Swan 1998. The opinion was put forward by Iraq’s representative, Dr Fadhil Jamail.

3. Ingrid Næser: Right Verus Might. Dissertation in history. Oslo 2005, p 29. The name of the man who probably shot Bernadotte is known, but despite the demands of the Swedish Foreign Ministry for an investigation, no Israeli government has ever tried anyone for the murder.

4. Næser, pp. 105-110. In the conclusion of her dissertation Næser claims that the armistice agreement between Israel and Egypt was dictated by Israel through Trygve Lie and President Truman, and that Bunche played “the role of an errand boy” (p. 110).

First published 9 December 2006

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.