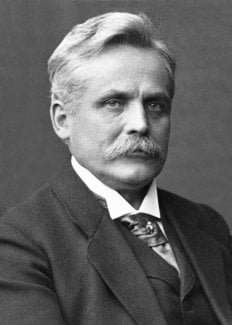

Wilhelm Wien

Biographical

Wilhelm Wien was born on January 13, 1864 at Fischhausen, in East Prussia. He was the son of the landowner Carl Wien, and seemed destined for the life of a gentleman farmer, but an economic crisis and his own secret sense of vocation led him to University studies. When in 1866 his parents moved to Drachstein, in the Rastenburg district of East Prussia, Wien went to school in 1879 first at Rastenburg and later, from 1880 till 1882, at the City School at Heidelberg. After leaving school he went, in 1882, to the University of Göttingen to study mathematics and the natural sciences and in the same year also to the University of Berlin. From 1883 until 1885 he worked in the laboratory of Hermann von Helmholtz and in 1886 he took his doctorate with a thesis on his experiments on the diffraction of light on sections of metals and on the influence of materials on the colour of refracted light.

His studies were then interrupted by the illness of his father and, until 1890, he helped in the management of his father’s land. He was, however, able to spend, during this period, one semester with Helmholtz and in 1887 he did experiments on the permeability of metals to light and heat rays. When his father’s land was sold he returned to the laboratory of Helmholtz, who had been moved to, and had become President of, the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, established for the study of industrial problems. Here he remained until 1896 when he was appointed Professor of Physics at Aix-la-Chapelle in succession to Philipp Lenard. In 1899, he was appointed Professor of Physics at the University of Giessen. In 1900 he became Professor of the same subject at Würzburg, in succession to W.C. Röntgen, and in this year he published his Lehrbuch der Hydrodynamik (Textbook of hydrodynamics).

In 1902 he was invited to succeed Ludwig Boltzmann as Professor of Physics at the University of Leipzig and in 1906 to succeed Drude as Professor of Physics at the University of Berlin; but he refused both these invitations.

In 1920 he was appointed Professor of Physics at Munich, where he remained throughout the rest of his life.

In addition to the early work already mentioned, Wien worked, at the Physikalisch-Technische Reichsanstalt, with Holborn on methods of measuring high temperatures with the Le Chatelier thermoelements and at the same time did theoretical work on thermodynamics, especially on the laws governing the radiation of heat.

In 1893 he announced the law which states that the wavelength changes with the temperature, a law which later became the law of displacement.

In 1894 he published a paper on temperature and the entropy of radiation, in which the terms temperature and entropy were extended to radiation in empty space. In this work he was led to define an ideal body, which he called the black body, which completely absorbs all radiations. In 1896 he published the formula of Wien, which was the result of work undertaken to find a formula for the composition of the radiation of such a black body. Later it was proved that this formula is valid only for the short waves, but Wien’s work enabled Max Planck to resolve the problem of radiation in thermal equilibrium by means of quantum physics. For this work Wien was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for 1911. An interesting point about it is that this theoretical work came from an Institute devoted to technical problems and it led to new techniques for illumination and the measurement of high temperatures.

When Wien moved, in 1896, to Aix-la-Chapelle to succeed Lenard, he found there a laboratory equipped for the study of electrical discharges in vacuo and in 1897 he began to work on the nature of cathode rays. Using a very high vacuum tube with a Lenard window, he confirmed the discovery that dean Perrin had made two years earlier, that cathode rays are composed of rapidly-moving, negatively-charged particles (electrons). And then, almost at the same time as Sir J.J. Thomson in Cambridge, but by a different method, he measured the relation of the electric charge on these particles to their mass and found, as Thomson did, that they are about two thousand times lighter than the atoms of hydrogen.

In 1898 Wien studied the canal rays discovered by Goldstein and concluded that they were the positive equivalent of the negatively-charged cathode rays. He measured their deviation by magnetic and electric fields and concluded that they are composed of positively-charged particles never heavier than electrons.

The method used by Wien resulted some 20 years later in the spectrography of masses, which has made possible the precise measurement of the masses of various atoms and their isotopes, necessary for the calculation of the energies released by nuclear reactions. In 1900 Wien published a theoretical paper on the possibility of an electromagnetic basis for mechanics. Subsequently he did further work on the canal rays, showing, in 1912, that, if the pressure is not extremely weak, these rays lose and regain, by collision with atoms of residual gas, their electric charge along their course of travel. In 1918 he published further work on these rays on the measurement of the progressive decrease of their luminosity after they leave the cathode and from these experiments he deduced what classical physics calls the decay of the luminous vibrations in the atoms, which corresponds in quantum physics to the limited duration of excited states of atoms.

In this, and other, respects Wien’s work contributed to the transition from Newtonian to quantum physics. As Max von Laue wrote of him, his “immortal glory” was that “he led us to the very gates of quantum physics”.

Wien was a member of the Academies of Sciences of Berlin, Göttingen, Vienna, Stockholm, Christiania and Washington, and an Honorary member of the Physical Society of Frankfurt-on-Main.

In 1898 he married Luise Mehler of Aix-la-Chapelle. They had four children. He died in Munich on August 30, 1928.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

The Nobel Foundation's copyright has expired.Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.