“We’re in this forever” – the history of the Nobel Foundation

The Nobel Foundation was founded in 1900, four years after Alfred Nobel’s death. It was set up primarily to invest Nobel’s fortune but also to manage the immaterial value of the Nobel Prize. While the first task remains basically the same after more than a century, the second has grown in importance as the prize has accumulated prestige over the years. Learn more about the Nobel Foundations’ work in this overview.

The creation of the Nobel Foundation

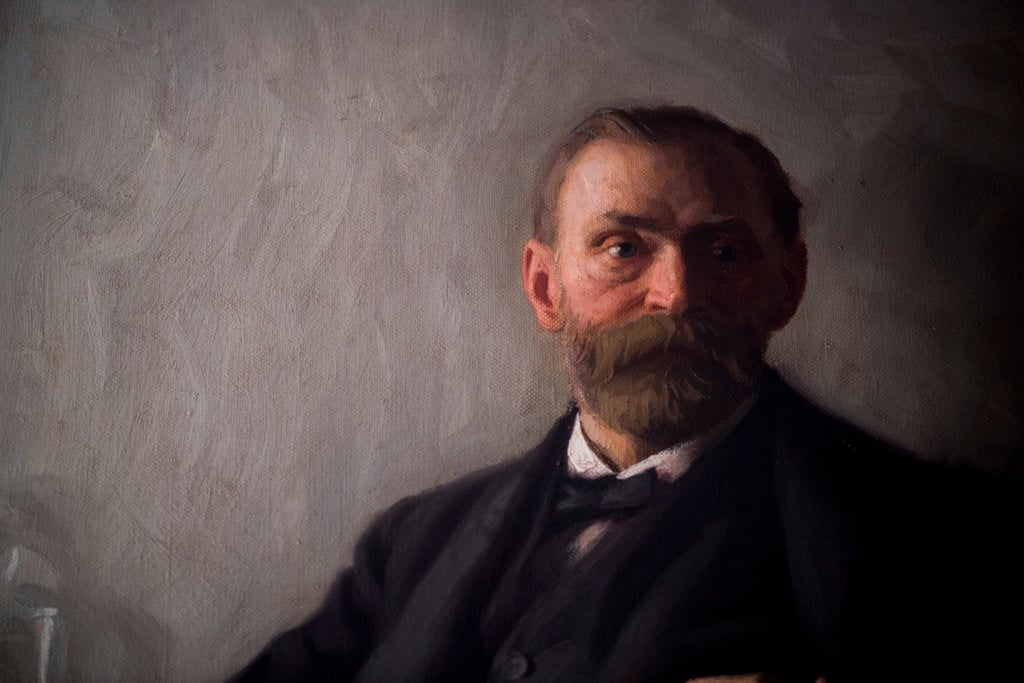

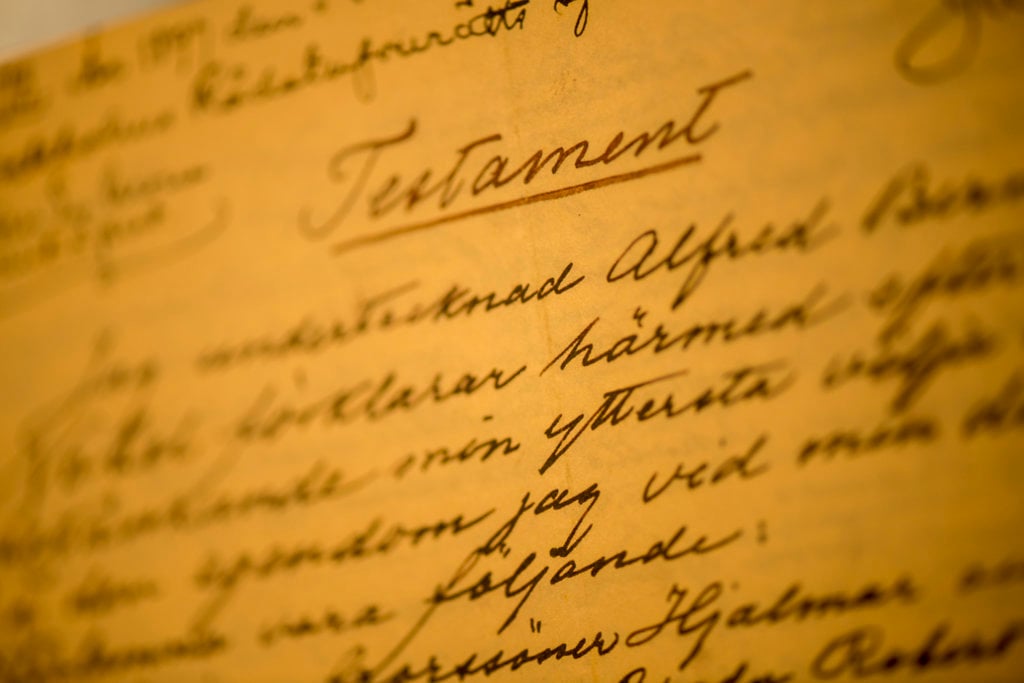

Alfred Nobel died on 10 December 1896. His will was opened shortly after, revealing that he had donated most of his fortune to the establishment of prizes to people who had “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind.” He also appointed two executors of the will, whose duty was to create an organisation for the prize. Their task in the subsequent years was to negotiate how this prize was to be set up, with Nobel’s relatives and the Nobel Prize-awarding institutions: the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences for the Nobel Prizes in Physics and Chemistry, Karolinska Institutet for the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, the Swedish Academy for the Nobel Prize in Literature, and a committee of five persons to be elected by the Norwegian Parliament (Storting) for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Some members of the Nobel family were unhappy with the will and sued the executors in a bid to take control of the funds. They argued that the prize as it was written in Nobel’s will was too vague to be realised and that Nobel’s money would be wasted. They also feared that the prize awarding institutions would use the Nobel funds to enrich themselves. Therefore, when a settlement was eventually reached, it included guarantees that the prize awarders would stay true to Nobel’s intentions. One of these was that the prize should not be shared between more than three people.

It was by no means obvious that the prize-awarding institutions would accept the task of giving out large international prizes.

Although many Swedish newspapers anticipated the prize’s future greatness, it was not at all clear that the prize would be a success. Doubts were raised by, among others, the New York Times, which wrote in 1897 that the donation meant that: “a number of eminent men of Norway and Sweden have a task before them which will inevitably bring to them more trouble than glory.”

However, it was imperative that the prize-awarders accept the task, otherwise there would be no prize. The main discussions took place during 1898–1899, in a small group made up of representatives from the prize-awarders to be. At this point, the only institution that had accepted the task was the Storting, the Norwegian Parliament.

Two factors were crucial for the other awarders to accept. The first was setting up a reliable system for finding the laureates – the nomination system – and the second was the creation of research institutes, so-called Nobel Institutes. These institutes would be funded by the Nobel Foundation but belong to the prize awarding institutions. The hope was that with these Nobel Institutes, Stockholm would become a new centre in the scientific world – and that the Nobel Prize would function as a way to direct attention to the Nobel Institutes.

A new prize

In 1968, Sweden’s central bank – Sveriges Riksbank – celebrated its tercentenary. Part of the celebrations was to create a prize in economic sciences. Representatives from the bank and from the Nobel Foundation held meetings throughout 1967 about the possibility of making this prize “a sixth Nobel Prize.” During the process, the prize-awarding institutions, the Nobel Prize laureates and members of the Nobel family were all informed about the discussions.

The result was a prize created in 1968 – and first awarded in 1969 – but it did not become a Nobel Prize. This was not possible as the Nobel Prizes are by definition those mentioned in the will of Alfred Nobel. Instead, it was a prize “in memory of Alfred Nobel”. Regarding the funding, it was decided that the bank would make a donation each year to the foundation, which would cover the prize amount, the administrative costs for selecting the laureates, and a share of the cost for the Nobel Prize festivities. The new prize was called the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel. Due to the length of its official name people soon started calling the Nobel Prize in economic sciences. However, it should more accurately be referred to as simply ‘the prize in economic sciences.’ What makes the prize close to a Nobel Prize is not the name, but that it is awarded by one of the Nobel Prize-awarding institutions, thus following the same thorough selection process as the Nobel Prizes.

When accepting the donation from Sveriges Riksbank and setting up the prize in economic sciences, the Nobel Foundation stated that this was to be seen as an ad hoc decision and that the establishment of this prize was not meant to open the doors for new prizes in other categories. This did not stop people from trying.

Already in December 1968, an American philanthropist proposed a Nobel Prize in architecture. These kinds of suggestions kept appearing in the following years.

Some were quite serious, such as the idea of a prize in environmental sciences from a member of the Nobel family and a prize in agriculture suggested by Nobel Prize laureate Norman Borlaug. Other were taken less seriously, such as a prize for popular music or ballet. It was not that these were not worthwhile pursuits, but that they did not have any relation to Nobel. In all cases, serious or not, the Nobel Foundation’s reply was that no new Nobel Prizes were to be created.

The Nobel system

The history of the Nobel Foundation can roughly be divided into three phases. The first covers the formative years of 1900 to the 1920s. During this period there was at first an ambition to make the Nobel Foundation a unified institution. However, the prize awarding institutions were more interested in making the Nobel Institutes closely connected with themselves, which meant that the Nobel Foundation took on a more administrative and representative role. It focused on the investments and on arranging the prize award ceremony. This was manifest in the plans for building a large ‘Nobel Palace’ where the prize would be awarded. When this proved to be too expensive, the foundation settled for holding the ceremony in the city’s new Concert Hall, followed by a banquet in the likewise new City Hall. While this meant a slightly less visible role for the Nobel Foundation, it also made it a more integral part of the public life in Stockholm.

In the second phase, from the 1920s to the 1960s, the Nobel Foundation became a funding agency in a way that it had not been before or since.

At this time, when the Nobel Institutes were started, the prize-awarding institutions made good use of the Nobel funds as a scientific resource. In this way, the Nobel Foundation played a significant role in a time before government funding for research existed in Sweden. This role waned after World War II, when research councils were set up. Eventually, the Nobel Institutes were either closed or shifted to government ownership, and thus ended the second phase in the foundation’s history.

During this phase, investing Nobel’s money was still of utmost importance, as well as arranging the Nobel Prize festivities. However during the 1970s until the 1990s the public aspects of the prize became more of a priority for the foundation. One of the priorities of this period was to modernise the award ceremony and banquet. This was done through a series of careful steps and culminated in a large jubilee in 1991, when the foundation’s 90th anniversary was celebrated with the most ambitious festivities to date. The increasing interest in the public image of the Nobel Prize kept growing in the 1990s and led to the establishment of a website (nobelprize.org) in 1995, a Nobel Museum in 2001 and a Nobel Media company in 2004.

The 1970s to the 1990s saw modernisation of the ceremonies and to some extent media relations, while the period from the mid-1990s to today built a new structure for public relations. This accelerated in the 2010s, with plans for creating a new and ambitious Nobel Center in Stockholm, and Nobel Media arranging international public events. The Nobel Museum – now renamed the Nobel Prize Museum – has already been a presence in Stockholm, as well as producing travelling exhibitions, since 2001. In 2004, the Nobel Peace Center was opened in Oslo. To this was also tied an ambitious digital strategy, with the numbers of followers in social media increasing from a few hundred thousand to several millions.

Taken together, the view emerges of the Nobel Foundation not only stewards, but also promoters of the legacy of Alfred Nobel.

The Nobel system in Norway

The Norwegian Nobel Committee and its own system of institutions have through history operated with a high degree of autonomy from the Nobel Foundation. The last decades have seen the two parts of the system getting closer, starting with the Norwegian Nobel Committee getting a representative on the board of the Nobel Foundation in 1985, and the renovation of the Norwegian Nobel Institute at the same time. In the 1990s, the Norwegian Nobel Institute also received funding for new offices for researchers, which helped raise the standard of the research carried out there further.

It is interesting to note that of all the Nobel Institutes created, the only one still in operation is the Norwegian Nobel Institute. This is most likely due to the fact that all the other prize-awarding institutions already existed before the prize was established and had an organisation prior to this which could use the resources in several ways. The Norwegian Nobel Institute, on the other hand, was set up to be the institutional framework for the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

While the Norwegian Nobel system might in one sense be smaller, in that there are fewer institutions and fewer people employed, it is also larger in the sense that the Nobel Peace Prize attracts most international attention of all the categories. While the science and literature prizes are important cultural events, the Nobel Peace Prize aims to affect policy on a high global level. It can also elevate human rights activists and peace organisations from relative obscurity to a world stage – and this also means that the prize is always controversial and debated.

The Nobel Foundation and the future

One of the most important projects for the Nobel Foundation in the 2020s is the planned construction of a Nobel Center in Stockholm. In 2031, you will be able to explore the work and the ideas of the laureates in a new public building. The Nobel Center will be a space for dialogue between science, literature, and peace efforts – brought to life through exhibitions, workshops, lectures, cultural events, and family activities. Situated by the waterfront it will be a meeting place for people of all ages and interests where the aim is to explore topics and questions that matter, inspired by the Nobel Prize’s legacy. While part of the motivation for this building was to create a venue that could accommodate more visitors interested in the Nobel Prize, there was also a deeper purpose – to further and spread the values that the foundation feels that the prize represents. These can be summed up in the words of the opening address at the award ceremony in 2017:

Alfred Nobel dreamed of a better world. And in many ways the world has become a better place since he wrote his will in the late 19th century. Thanks to scientific, cultural and economic developments, more people have the opportunity to fulfill themselves and to live long and rich lives. Scientific achievements have not only made new technologies possible; they have also given us a deeper understanding of how everything in our universe functions − from the stars to the cells in our bodies. Cultural advances have lessened the impact of prejudice and tradition. Economic growth has laid the groundwork for technological and social progress as well as material wealth. We now have societies where people are able to live the lives they desire to a degree the world has never seen before.

The capital of the Nobel Foundation

The will of Alfred Nobel states that his assets, “converted to safe securities”, should constitute a fund, “the interest on which is to be distributed annually as prizes.” Together with negotiating with the relatives and the prize awarding institutions, this was the major task that the executors of the will had in front of them. And it was no simple task. Nobel’s fortune was large, some 33 million SEK (which today would be approximately 2 billion SEK) and these funds were not readily available to easily transfer from the death estate to the foundation.

Nobel had been an international businessman with investments all around the world.

Moving the money to a Swedish foundation was complicated and required complicated negotiations with the tax authorities in the countries where Nobel had investments. However, the executors succeeded, with the fortune only diminishing slightly, from 33 to 31 million.

Nobel’s will only said that his fortune should be converted into “safe securities” and that the interest from these investments should be given out as prize money. This meant that the financial aims of the Nobel Foundation was to make sure that the investments yielded enough revenue to keep the prize sum high, while still financing the prize awarders and the Nobel Institutes – preferably with the capital growing.

Despite their best efforts, the fortune decreased over the coming decades. This was due to two factors: the first was the conservative investment strategy that followed from Nobel’s word “safe” in the will, which led to three kinds of investments: bonds in companies, real estate in Stockholm and lending money to Swedish municipalities, while the second factor was taxes. In 1904 an attempt was made to grant a tax exemption through a parliamentary bill, but it did not pass.

At this time, however, taxes were not high and the small decline could be blamed on money spent on Nobel Institutes. But the situation grew worse during and after World War I, when both costs and taxes rose – leading to a worrying decrease in the prize sum. For a long time the Nobel Foundation was the largest tax payer in Sweden. The press was generally sympathetic to the foundation – it was considered short-sighted for the government to tax an institution that contributed to the international status of Sweden.

The Nobel Foundation was ready to fight the issue out, and after the war it started a legal campaign that resulted in large reductions in the foundation’s tax burdens after 1927. In this, the foundation again had the press on their side, which could be seen most clearly in 1925, a year when all the prize-awarding institutions decided to not award prizes. This was seen as a protest and was not criticised. On the contrary, it gained sympathy for the Nobel Prize and vilified the authorities. The foundation also enrolled Emanuel Nobel, Alfred Nobel’s nephew and confidante, to their cause. The campaign was effective, and eventually the parliament granted the foundation a tax cut from 40% to 3%.

While this stabilised the finances, it was not really a tax exemption, just a one-off cut. Soon taxes started going up again. While slow at first, in 1938 they were still only at 5%, after World War II they had risen to 21%. The question was brought before the parliament again, and this time the argument that the Nobel Foundation should be counted as an academy was successful, and in 1946 the Nobel Foundation became tax exempt. It is likely that this outcome was affected by the lawmakers being even more aware of the Nobel Prize’s status at this time.

Cutting taxes stopped the decline, but it was only when the investment rules were changed that the capital could grow. So, while the funds did not decrease after a tax exemption in 1946, they did not really start to grow until the 1980s. At that time, however, they grew fast, eventually quadrupling over a 20-year period.

The rules had undergone some previous alterations. In 1939 the foundation was allowed to invest in real estate.

In the 1940s and 1950s the foundation invested a lot in real estate both in Stockholm but also to a high degree in other cities.

This was done as a precaution: in case of a Soviet nuclear strike, this would leave some of the Nobel Foundations investments intact.

The 1970s saw the beginning a period of modernisation, and one goal was to get the fortune back to its 1901 value. This was not done because the money was important for the prize’s status; on the contrary, executive director Stig Ramel believed that the prestige of the prize had transcended the monetary value of the award. The main reason was instead that he felt that the foundation had a moral obligation to restore the fortune to the state it had been in when Alfred Nobel made his donation.

This was done partly through further changing the rules, allowing up to 60% of the capital to be invested in shares, and partly through a series of strategic real estate investments which led to a substantial increase in the funds during the 1970s and early 1980s. In the mid 1980s higher taxes made the real estate less profitable, and the foundation made the decision to phase these investments out. The process was very profitable – and it also saved the Nobel Foundation from much of the trouble during the real estate crash in Sweden in the early 1990s. Today, the only building the foundation owns is its own office building at Sturegatan 14 in Stockholm.

In 1991, the funds were back to their original size, and kept growing. During the 1990s, rules changed again, and up to 70% of the capital was invested in shares. This contributed to the decrease during the dot com-crash around 2000, when the value went from almost 5 billion to little more than 3 billion SEK – a loss of almost 30%. Some of this was regained, but then the foundation sustained heavy losses during the crisis in 2008–2009. In the 2010s, the foundation has worked to stabilise its investments, through balancing different assets. In this period, shares have made up about 40%, bonds 20% and 40% is in other investments, mainly hedge funds.

During this latter period, the Nobel Foundation has also organised its investments in a more formalised way, through creating an investment committee to aid the foundation’s CEO and CIO. It consists of experts from business and academia, and its task is to ensure that the Nobel Foundation’s assets are invested in such a way that they will continue to generate revenue for the prize with a long-term perspective, or in the words of the foundation’s former CEO Lars Heikensten: “We’re in this forever”.

Nobel Week

Every year in December, the Nobel Prize laureates come to Stockholm or, in the case of the peace laureates, Oslo to be honoured at the Nobel Prize award ceremony and at the banquet on 10 December, the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

Stockholm festivities

The award ceremony and banquet are the highlights of a whole week of activities for the laureates in Stockholm, organised by the Nobel Foundation. During their stay, the laureates also visit the prize awarding institutions, universities and schools. They give public lectures, and they take part in press conferences and give interviews. One might think that this attention is a result of today’s media landscape, but it has been present from the outset. In 1901, newspapers sent reporters to the laureates’ hotel room, and sketch artists waited in the hotel lobby in order to get a glimpse of the famous scientists.

The laureates’ usually try to take part in as many activities as they can, but there is actually only one requirement: the Nobel Prize lecture, where they speak about their prize awarded work to a scientific or literary audience. These lectures are later published in the Nobel Prize’s yearbook, together with a biographical essay that the laureates provide, as well as the banquet speech.

10 December

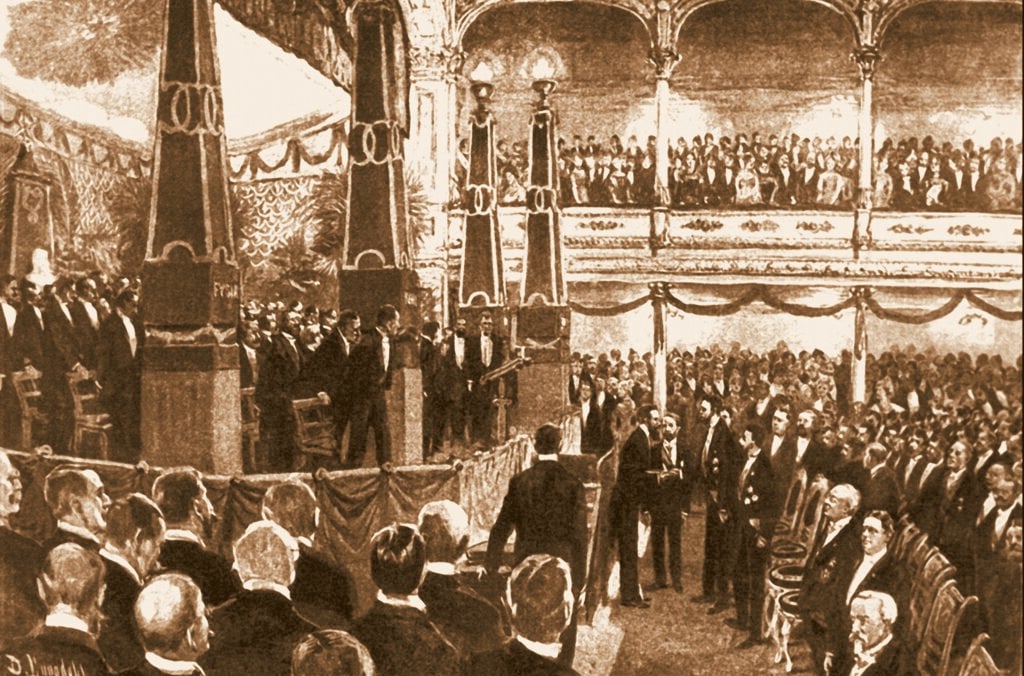

The Nobel Prize award ceremony in Stockholm is a long-held tradition, with the first ceremony having taken place in 1901, on the occasion of the very first set of Nobel Prizes. There has been just one change in schedule to this date – for the 1919 prizes – the first to be awarded after the end of World War I. That year the award ceremony was moved to June of the following year with the hope of brighter more festive weather. The ceremony took place on 2 June 1920 at the Royal Academy of Music, with the subsequent banquet at the Hasselbacken restaurant near the Skansen outdoor museum. This was not a success. No members of the Royal Family were present because of the death of Crown Princess Margaretha. The weather was gray, rainy and cold. From then on, the ceremony returned to its traditional 10 December date, where it has remained ever since.

The award ceremony has taken place in the Concert Hall since the building was completed in 1926. Prior to that, the ceremony was held in the Musical Academy. The content has been largely the same since 1901.

First there is a speech by the chair of the Nobel Foundation on the situation for science and progress in the world. After this a representative from the Nobel Committee for physics gives a speech about the work of the physics laureate, traditionally in Swedish with just a few remarks at the end in the laureates’ native language or English. After the speech the laureates receive the prize from the Swedish king, take a bow and return to their seat. This is then repeated for all the laureates, following the order in which the categories are mentioned in Nobel’s will: physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine and literature, ending with the memorial prize for economic sciences. In-between the speeches, music is performed by the Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra.

What has changed over the years are the optics of the ceremony.

During the first years, both laureates and the royal family were placed in the first row in the audience, with an orchestra or choir onstage. The speakers also had a pulpit onstage, but once the speech was over the award was presented to the laureate on the floor in front of the stage, making it hard for most of the audience to see. In fact, the laureates were not visible at all to most of the guests. This started to change in 1912, when the laureates and the speakers were placed on stage. After this, more and more people moved up, until finally in 1973 the new king agreed to be placed on the right side of the stage. This also meant that the medals and diplomas were also given away where everyone could see it – not least the TV-cameras.

After the award ceremony comes the banquet. It was started as an afterthought when, just a few weeks before the first award ceremony in 1901, the board decided to hold a dinner for a select few of the guests. This was held at the Grand Hôtel, the same hotel where most of the laureates were staying. In the 1930s it was moved to the City Hall’s Golden Hall, which could accommodate more people, increasing the size from 200 to about 500 guests.

Those invited to the banquet were the laureates, the royal family and members of the prize awarding institutions. Since the Nobel Foundation wanted to make the connection between the prize and official society in Sweden clear, invitations were also sent to the court, to government officials and diplomats. Eventually, the guest list also included people who have made donations to the prize awarding institutions or other parts of the Nobel system as well as politicians from the Swedish parliament.

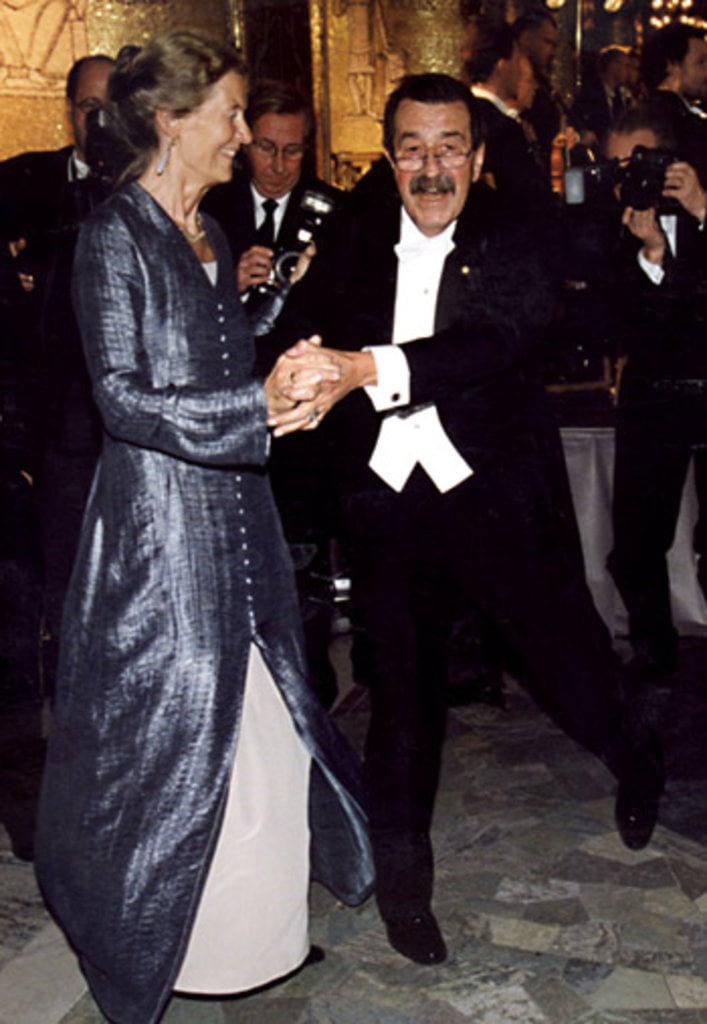

The Nobel Prize banquet as it is today was created in a process starting in the 1970s, when the foundation contacted the director of the Royal Dramatic Theatre for advice on how to make the banquet into a spectacular event in its own right. Together, they found inspiration in the festive meals from the Baroque era, when everything from food to music and dance was incorporated into a whole, making banquets into performances. The same was then done with the Nobel Prize dinner. The speeches from the laureates were shortened and placed together as a highlight at the end of the dinner. Before that was music entertainment and dance, often coordinated with the serving of food. The foundation has gastronomical advisers that have a good overview of chefs working in Stockholm – it is considered an honour to be selected as chef for the Nobel Prize banquet. Since they have the job for a limited number of years, usually two or three, they try their hardest to make the dinner memorable.

Apart from the laureates, prize-awarding institutions, politicians and donors, there is an important category of guests: students.

Their presence at the ceremony and at the banquet is a symbol of continuity – the laureates have made achievements in the past, and the students represent the future. Students started being present in 1935, when they paid a tribute to the laureates during dinner. Afterwards they could stay in the City Hall and eat a buffet, however not in the same room as the other guests. After the dinner, the students started the dance in the Blue Hall, the largest room in the City Hall.

Nobel Prize laureate Günter Grass and his wife take to the dance floor.

© The Nobel Foundation 1999. Photo: Hans Pettersson

In 1974 the banquet was moved to the Blue Hall, which doubled the number of guests from about 600 to 1,300. The Blue Hall can be reached from the second floor on a monumental marble staircase, so this also enabled one of the most ceremonial parts of the dinner – the procession of the guests of honour. Today, the guests not seated at the table of honour arrive first, and have to be in their seats at 19:00. Shortly after this, the 88 people seated at the table of honour – a long table running through the middle of the room – march down the staircase while festive music is playing. The people in the procession are the royal family, the laureates and their spouses, the board of the Nobel Foundation, the speaker of the Swedish parliament and parts of the government, including the Prime Minister.

Nobel Day in Oslo

When the Nobel Prize started, the names of the laureates were meant to be revealed to the public on 10 December. This proved to be very hard, not least since the laureates themselves needed to be informed so that they could plan the trip to Stockholm. In combination with the rules of secrecy being less tightly adhered to than today, this meant that when the day came, the press had already revealed their names several weeks ahead. This led to the eventual change of this practice, so that the names were revealed to the press as soon as the decision was made.

In Oslo, where the Nobel Peace Prize is awarded, they did not have this problem, since they did not have an award ceremony during the prize’s first years. The Nobel Committee only announced the name of the laureate on 10 December, first at a short ceremony in Stortinget and after 1905 in the new Norwegian Nobel Institute.

But while not inviting the laureates had the benefit of making it easier to keep their names secret, it had the drawback of being less festive than the celebrations in Stockholm, and soon a ceremony in Oslo was developed as well. It was held in the Nobel Institute until 1947 when it moved to the University of Oslo and then in 1990 moved to the Oslo City Hall. That was also the year when the Nobel Peace Prize lecture, which previously had been held on the next day, became part of the award ceremony.

The award ceremony in Oslo differs from the Swedish ceremony in important ways. The main event is the same – a presentation speech from the prize awarding institution followed by the laureate accepting the prize. However, in Oslo the prize is presented to the laureate by the chair of the Nobel Committee, not by the Norwegian king. The royal family have places in front of the stage, but not on stage.

Whether laureates attend a ceremony in Stockholm or Oslo, both occasions are a memorable and ceremonial event. Even though you are technically a Nobel Prize laureate as soon as the decision is made in October, the award ceremony and banquet are the symbolic representation of that. This was expressed by Seamus Heaney in his speech at the banquet in 1995:

Today’s ceremonies and tonight’s banquet have been mighty and memorable events. Nobody who has shared in them will ever forget them, but for the laureates these celebrations have had a unique importance. Each of us has participated in a ritual, a rite of passage, a public drama which has been commensurate with the inner experience of winning a Nobel Prize. The slightly incredible condition we have lived in since the news of the prizes was announced a couple of weeks ago has now been rendered credible. The mysterious powers represented by the words Nobel Foundation and Swedish Academy have manifested themselves in friendly human form.

Published August 2025

Nobel Prize announcements 2025

This year’s Nobel Prize announcements will take place 6–13 October. All announcements will be streamed live here on nobelprize.org.