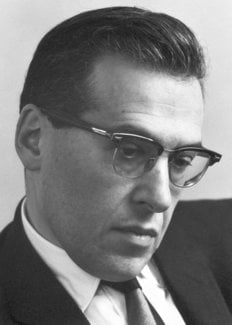

Julian Schwinger

Biographical

Julian Schwinger was born on 12th February 1918 in New York City. The principal direction of his life was fixed at an early age by an intense awareness of physics, and its study became an all-engrossing activity. To judge by a first publication, he debuted as a professional physicist at the age of sixteen. He was allowed to progress rapidly through the public school system of New York City. Through the kind interest of some friends, and especially I.I. Rabi of Columbia University, he transferred to that institution, where he completed his college education. Although his thesis had been written some two or three years earlier, it was in 1939 that he received the Ph.D. degree.

For the next two years he was at the University of California, Berkeley, first as a National Research Fellow and then as assistant to J.R. Oppenheimer. The outbreak of the Pacific war found Schwinger as an Instructor, teaching elementary physics to engineering students at Purdue University.

War activities were largely confined to the Radiation Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Being a confirmed solitary worker, he became the night research staff. More scientific influences were also at work. He first approached electromagnetic radar problems as a nuclear physicist, but soon began to think of nuclear physics in the language of electrical engineering. That would eventually emerge as the effective range formulation of nuclear scattering. Then, being conscious of the large microwave powers available, Schwinger began to think about electron accelerators, which led to the question of radiation by electrons in magnetic fields. In studying the latter problem he was reminded, at the classical level, that the reaction of the electron’s field alters the properties of the particle, including its mass. This would be significant in the intensive developments of quantum electrodynamics, which were soon to follow.

With the termination of the war Dr. Schwinger accepted an appointment as Associate Professor at Harvard University. Two years later he became full Professor. That was also the year of his marriage to Clarice Carrol of Boston.

In subsequent years, he worked in a number of directions, but there was a pattern of concentration on general theoretical questions rather than specific problems of immediate experimental concern, which were nearer to the center ot hls earlier work. A speculative approach to physics has its dangers, but it can have its rewards. Schwinger was particularly pleased by an anticipation, early in 1957, of the existence of two different neutrinos associated, respectively, with the electron and the muon. This has been confirmed experimentally only rather recently. A related and somewhat earlier speculation, that all weak interactions are transmitted by heavy, charged, unit-spin particles still awaits a decisive experimental test. Schwinger’s policy of finding theoretical virtues in experimentally unknown particles has culminated recently in a revived concern with magnetically charged particles, which may also be involved in the understanding of strong interactions.

In later years, Schwinger has followed his own advice about the practical importance of a phenomenological theory of particles. He has invented and systematically developed source theory, which deals uniformly with strongly interacting particles, photons, and gravitons, thus providing a general approach to all physical phenomena. This work has been described in two volumes published under the title “Particles, Sources, and Fields“.

Awards and other honors include the first Einstein Prize (1951), the U.S. National Medal of Science (1964), honorary D.Sc. degrees from Purdue University (1961) and Harvard University (1962), and the Nature of Light Award of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (1949). Prof. Schwinger is a member of the latter body, and a sponsor of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Julian Schwinger died on July 16, 1994.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.