Charles K. Kao

Biographical

Family Background

The Kao family comes from a township called Zhangyan in the Jinshan district near Shanghai, China1. As landowners, the family would have been considered wealthy. The sons of each generation would be well educated in the style of the times. My knowledge of the family’s genealogy goes back only to Grandfather.

Grandfather Kao Hsieh2 also went by the courtesy name Kao Ch’ui Wan3. He was a literary man, famous for his beautiful poems, which he would render in Chinese calligraphy; the combination of poetry with calligraphy is an art form of the East. As a Confucian scholar, he was a collector of books and also a prominent member of the Nan She (Southern Society). Other family members were also active in the Society; its aim during the 1911 Chinese Revolution was to help bring down the ruling Qing dynasty. A museum now erected in the town exhibits his work and also gives a history of the political activities the man participated in. He was of a liberal bent.

Grandfather had four sons and two daughters. My father, Kao Chun Hsin, was not the eldest of the sons. The eldest would have stayed in the town to look after the family properties and affairs; that is where those duties always fell. He was the third son. These sons were growing up as modern times were coming to China. After a good education in Shanghai, my father went to study for a year at the Michigan Law School. Before he left for the U.S.A., a marriage was arranged to a petite lady from one of the families in the social circle. She was left behind to wait for the return of the adventuring husband. Coming from an equally modern and intellectually accomplished family, the new wife was well educated and a poet herself.

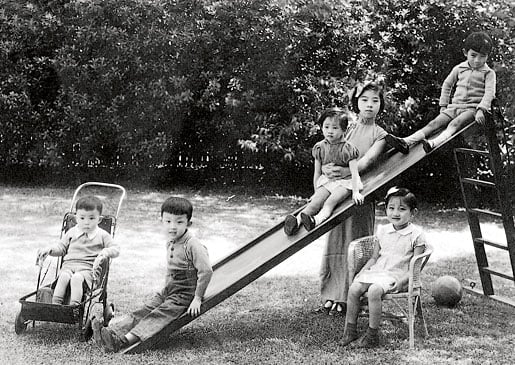

Figure 1. Charles Kao in 1942, with his younger brother and cousins in Shanghai, China. Second from left: young Charles Kao.

Those were the years when scions of the few wealthier middle-class families in China ventured out to Paris, to London, to New York, to further their experiences and studies. When they returned to China, they were welcomed with great enthusiasm.

On his return from the U.S.A., Kao Chun Hsin, a young man then only in his mid-twenties, was appointed to sit as the Chinese judge in the Court for International Law. He shared the bench with established judges from Western countries. With this prestigious appointment, he and his young wife moved to Shanghai, where they joined the social life of the city.

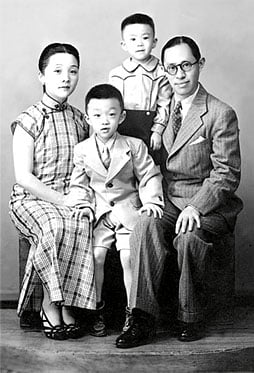

Figure 2. In 1942, young Charles Kao (second from left) with his family.

The first child born to the couple was a daughter, followed two years later by a son. Misfortune struck. In a measles epidemic, both children were stricken, and both died from complications, the elder child ten years old, the younger eight. The mother was small boned and of a delicate, fragile appearance. Childbirth would not have been easy. In the years after the tragedy, she had miscarriages one after another. Finally in 1933, I was born, for my parents happily a healthy child. My younger brother Timothy was added to the family four years later.

|

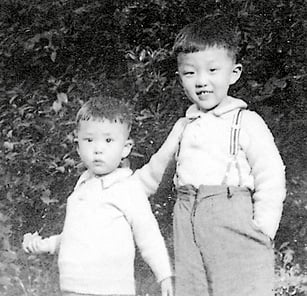

| Figure 3. Charles Kao in 1938, with his younger brother. |

Because of the earlier loss of the two elder siblings, my brother and I lived a very pampered and protected life. Nursemaids kept constant watch. With my parents busy at dinner parties and social events, we only met them as if for a daily royal audience. Later, home tutors came to give us lessons. The basic lesson plans were readings from the well-known classics, the Four Books4, which we learned to recite by memory. A second tutor taught English.

Finally, when I was ten, I was sent off to school. The driver dropped me off inside the school playground, telling me to wait and someone would tell me where to go. I had never seen so many kids running about so wildly in a crowd and stood wide-eyed.

A bell rang and soon the playground was empty, but for one solitary child. A kindly looking lady appeared and took me to my class. Maybe it was the home tutoring, or the late start to formal schooling, or an overly cautious and protective upbringing, but in any case I never became a talkative person. As an adult I am not always comfortable in social gatherings with small talk. I must have inherited my father’s gentle nature.

The primary school I attended in Shanghai was a very liberal one, established by scholars who had return from an education in France. The children of leading families were enrolled there, including the son of a well-known man, believed to be a top gangster of the underworld!

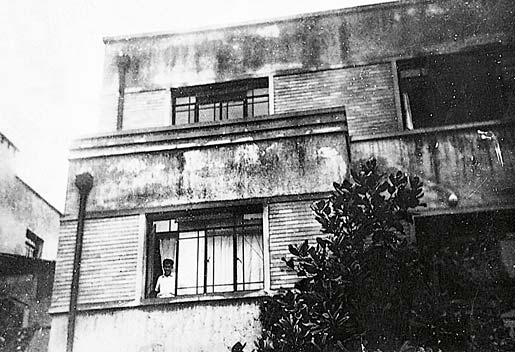

Figure 4. Kao’s old home in Shanghai, China.

By now the family had a home that was situated inside the French Concession. The International Settlements were in an area within the city where various Western powers held authority. These areas were generally kept free from the rough and tumble of the metropolis, providing a haven from the human poverty of China. The locals nicknamed this area shili yangchang (a ten-mile strip of foreign spectacles). So when the Japanese invaded China in the 1930s, these areas were off limits for the invaders.

The family was shielded from the horrors that occurred. With the chaos of war, the law courts were suspended, and social gatherings dried up. My parents stayed home more during this period, and we built a closer relationship with them. Together we played bridge and card games to pass the hours.

The cessation of war with Japan did not bring peace. Soon the Red Army, who had been fighting the Nationalist Government, was at the city gates. My father made the decision to leave. The topic had been discussed often over the family games of bridge and the various options mulled over. To move to Chungking5, or to join relatives in Taiwan, or perhaps there were relatives who lived in Hong Kong too?

In 1948, gathering a few belongings, the family boarded a ship that sailed out of Shanghai on a grey dismal wet day. The famous waterfront at the Bund slowly receded out of sight and that was the last we saw of our home city for many years.

A short sojourn in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, persuaded my father that Hong Kong would be a better haven. With help from maternal relatives in Hong Kong, the family found a small apartment and my brother and I were enrolled into St. Joseph’s College where our cousins also studied. As English was the preferred medium of instruction, the local dialect of Cantonese was not a requirement and I never felt the need to learn the tongue.

At 48, my father felt he was too old to study for the law exams that would qualify him to practice in Hong Kong. Instead he took on a job as legal adviser to a company and also taught a few Chinese law courses at local colleges. He became known in Hong Kong as the expert interpreter of the old Chinese laws. There were still some cases of family inheritance and such matters that would need expert advice of this type.

I did well academically, but did not apply myself much to athletics or sports during my five years at St. Joseph’s College. My ex-classmates, in later life, reported that they remember me as a quiet person who did not join in the rough and tumble of boy play. I managed almost straight A’s in the school matriculation examinations, which qualified me to apply for entry to the University of Hong Kong. However the University was still in some disarray after the war and not all faculties were functioning. I wished to study electrical engineering. Britain beckoned and the British Council in Hong Kong was helpful. In 1953 I boarded a P & O liner bound for England.

I enrolled at Woolwich Polytechnic in London, to sit for the A-level exams which I passed easily. I was so much at home at Woolwich Polytechnic that instead of applying for entry to the other more prestigious Colleges of London University, I continued on to study for my bachelor’s degree there. I graduated in 1957 with a B.Sc. in Electrical Engineering. In those days the degrees were awarded as a First, Second, Pass or Fail. As I spent more time on the tennis court than with my books, my degree was a Second.

It was necessary to immediately find a job. Financing my studies had been a heavy burden for my father. I joined Standard Telephones & Cables (STC), a British subsidiary of International Telephone & Telegraph Co (ITT) in North Woolwich, a factory located on the opposite bank of the Thames. As a trainee, I was rotated through different sections for a year before I decided that I liked the work in the microwave division. After two more years, I felt it was time to move on, and applied for a lectureship at Loughborough Polytechnic.

During my three years at STC, I met and married Gwen, a fellow engineer who worked in the lab one floor above my work bench. So we drove to Loughborough for the interview, I got the job, and we immediately set about to look for a home. Finding newly built homes, we put down a deposit on one and drove back to hand in our notices to STC.

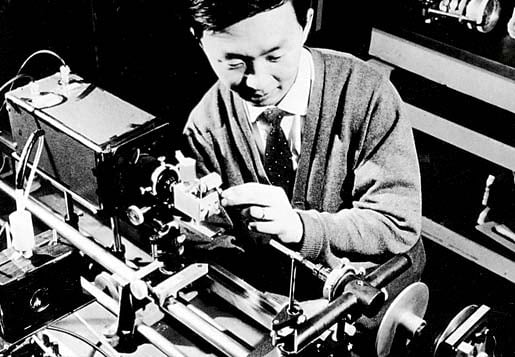

Figure 5. In 1965, the then young scientist Charles Kao doing an early experiment on optical fibers at the Standard Telecommunication Laboratories in Harlow, U.K.

However, It Was Not To Be

Someone in senior management had noticed how I had worked on the microwave projects and felt the promise I showed should not be lost to the company. The offer came immediately to allow me to transfer to the research lab, STL, in Harlow. To add incentive for me to stay, a job would be found for Gwen too at the new location. Loughborough had to be pacified and the lawyers got to work on that, and to get the house deposit refunded. The offer was too good to pass up, and my future was destined to take on this new course. I stayed with ITT Corp, working for the next thirty years at various locations, in the U.K., the U.S.A. and Europe.

During these years, in 1967 my parents emigrated to join us in the U.K.. They were then both in their late 60s and elderly, but still able to live independently. They were happy to see a grandson, born in 1961, and a granddaughter, born in 1963.

In 1970, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, CUHK, came calling. Would I come to the institution to set up an electronics department? STL agreed to give a two-year leave of absence, which then became four years. I was able to see the first batch of students graduate, and to establish a graduate program as well. During this time, 1970–1974, annual summer leaves were taken to return to STL to keep abreast of developments in the research field of optical fibers. It was also an opportunity to see my parents, who had remained in Harlow.

By 1974, the project I had seeded, with the now famous 1966 paper published in the IEE Proceedings, had progressed to the pre-production development stage. An industry had grown up around it and it was full speed ahead to revolutionize the telecommunications systems around the world. ITT wanted me back to be part of the team for this endeavor.

So the young family was uprooted again and the move this time was to the ITT plant in Roanoke, Virginia, in the U.S.A.. I was promoted to Chief Scientist, then Vice-President and Director of Engineering in charge of the electro-optical products division at ITT. During my years in the U.S.A., I continued to travel to other research labs around the world, to discuss progress, to encourage work, to keep abreast of the leading edge of the developments. It was a busy time. I always dropped by to visit my parents in the U.K..

In 1976, my mother died at the age of 76 years. My widowed father, who visited Roanoke once or twice, preferred his life in the U.K. and this situation continued until finally, in his eighth decade, he moved in to live with us, when we were back in Hong Kong again.

Figure 6. Charles Kao showed an early fascination with the properties of sand.

By the 1980s optical fibers were being laid across the world in vast quantities, and the industry had evolved into a giant. The capacity for communications had grown exponentially. In 1982 I was appointed Executive Scientist at ITT in charge of all research and development activities and I moved to the Advanced Technology Center in Connecticut, U.S.A.. This post was specially created and allowed me the freedom to do anything I considered important for ITT. In order to chart the waters on the ultimate limits of optical communication technology, I pioneered the Terabit Optoelectronics Technology Project to explore the technologies that could reach terabits per second of transmission capacity. The project involved a consortium of ten universities and institutions, and aimed at a goal that was three orders of magnitude higher than the then state-of-the-art. In 1985 I was appointed the Director of Corporate Research at ITT. During this time, many innovations by creative minds were evolving to make use of the increased capacity for sending information over the system. The internet was born.

In 1986, CUHK again came calling. This time the request was for me to accept the position as President of the University, the contract to begin in 1987. In British terminology, this position is known as the Vice-Chancellor6 of the University.

The second move to Hong Kong was made as ITT Corp began the process of selling off all its technical divisions in the U.S.A. to Alcatel, a French business. After thirty years it was a sad moment to part company with colleagues of long standing.

I spent nine years as the third Vice-Chancellor of CUHK. It was an interesting and challenging time, both for Hong Kong as it prepared for the resumption of sovereignty by China, and for the higher education sector, which saw a massive expansion and improvements in quality. During those years I sought to establish research more prominently as part of the normal work of the faculty, set up contacts with many leading institutions in the U.S.A. and the U.K., and set the University on a path to become a more well-known institution, competitive with the best institutions. I was especially pleased with the establishment of the Faculty of Engineering, in which information technology played a major role. A Faculty of Education was also established during those years. A number of research institutes also came into being. The University nearly doubled in size during those few years, and a fourth undergraduate college was established.

At the University, my role was to create space for people to grow. What I had done essentially was create situations where people would like to take on responsibilities. This had enabled the University to grow as a whole: everybody would be contributing what they should because they feel it is their responsibility and the environment allows them to do so. I created the space at the right time for talent within the University to perform as it should, thus taking it to a new level of development.

The rapid expansion of the tertiary education sector and the increased government funding that came with it have allowed us to do a lot of things to become a top university. The most satisfying change was a scholarly atmosphere on campus – people are pursuing important things because they believe such things are important.

It was perhaps natural that my advice was sought and I became involved in technology issues in the community, especially in relation to information technology. I was able to play a part in setting up an Internet exchange in Hong Kong (then a bit of a novelty and even now providing useful service), and in promoting the establishment of the Hong Kong Science Park.

My father died in 1996, just prior to my retirement from the University – a year before the return of colonial Hong Kong back to China. My father’s ashes were brought back to England to be laid to rest with my mother – in a cemetery in Harlow. After a year of lecture tours around S. E. Asia, I stayed in Hong Kong, setting up my own company for consultancy. I was appointed to a number of companies as non-executive director.7 In 2009, I moved to California to be closer to my two children.

Vignettes from Childhood and Working Life Memories

I had a fight with Lo, in my classroom. With our calligraphy brushes, we attacked and daubed each other’s faces and hands with black ink. The teacher was horrified. Lo, my mother warned me, was the son of a bad man. I was to be careful not to fight with the boy again. Otherwise school was fine. We sang French songs. The calligraphy teacher was very encouraging. This stroke is beautiful and will be marked with a red dot. But this one is leaning and unbalanced, it will get two red dots!

I made a good friend in primary school who liked to play with me at home. We got our driver to buy all sorts of chemicals. Reading from scientific magazines, together we experimented and made mud balls from phosphorous to throw at stray cats and dogs. The mud balls would explode with a bang and frighten the animals out of their wits! From glass bottles and such like I would fashion the funnels and beakers needed. I had bottles of cyanide and concentrated acids. One day as I was boiling up some nitric acid, the bottle exploded and the concentrated acid splashed onto my young brother’s trousers. It burnt the cloth entirely away but fortunately did not land on any of his skin! My parents were furious and confiscated all my chemicals, including the cyanide. I wonder where they disposed of the stuff.

One day my father brought home a big round yellow disc of food that he told us was called ‘cheese’ that foreigners ate. Food was in short supply so we ate it, but it tasted very funny. When we went outside for some walks we sometimes passed a big tall building with Japanese soldiers standing at the door. My parents told us to walk past quickly as people inside were killed there, and to bow to the soldiers.

It was sad to leave Shanghai, but I was fourteen years old and ready for new adventures. The war with Japan was also exciting. As we cowered under the desks, we could hear the aerial dogfight in the skies above. Peering from under, I could even catch a glimpse of the American planes chasing and diving after the Japanese planes!

So the waterfront of Shanghai faded away and we went to Hong Kong. The schooling there was easy and the book work was not hard at all. The class went on a field trip and some of my classmates got lost in the hills until it was pitch dark and they could see “tigers”! I was not in that group, but now, whenever we have a class re-union, the boys will relate their adventures with gusto and lots of laughs. So my years in Hong Kong passed by swiftly and I was to embark on my next adventure all by myself.

On the boat to England to study electrical engineering, I shared a cabin with three others. Two worked for the Hong Kong Government and were going to England to attend some courses relevant to their work, meteorology and water treatment respectively. The third was a professor of mathematics. During the sea trip, which lasted six weeks, the professor taught me quantum mechanics. He also took some other young students and myself under his wings. He escorted us to his friend’s home when we stopped at Singapore and taught us all to eat hot curry and to wash the fiery food down with beer.

I was nineteen years old and had never before left my family to be on my own. Everything was a new experience. To put my foot down on the soil at Port Said so I could tell myself I had been to Africa, to sail pass the Straits of Gibraltar and say I had seen Europe and the Sahara, to find England a cold and grey land! Little did I think eleven long years would pass by before I would see my parents again.

The British Council staff met me and arranged lodgings for me with a landlady in a house in Plumstead Commons, near the Woolwich Poly. Her house was old and large, with rooms for several lodgers. We all ate breakfast and dinner together under the stern eyes of the landlady. Food was still scarce after World War II and the slices of meat served for dinner were so thin, they were transparent when held up to the light! After such a sparse meal, we all trooped out for ‘fresh air’, but the real reason was to buy fish and chips, which we scoffed down hungrily on the walk back up the hill. The habit remains; I still love fish and chips.

After graduation in 1957 from the Polytechnic, I joined STC and had to walk through the tunnel under the River Thames every day to work. My first project was to build an amplifier and I got out my books to study the theories. My boss came by and said to put away the books, just do it. School work is to exercise the brain so it can think intelligently. There was no need for more revamping of theories!

I met my wife-to-be at work. She was an engineer in the coil section. We were married in 1959 and our children were born, a son in 1961, and a daughter in 1963. By then we were living in Harlow and working at STL.

The research was enthralling work and in 1966 I published the now famous ground-breaking paper, “Dielectric-fibre Surface Waveguides for Optical Frequencies”. This research was to spawn a whole new industry over the next twenty years.

People asked me if the idea came as a sudden flash, eureka! I had been working since graduation on microwave transmissions. The theories and limitations were ground into my brain. I knew we needed much more bandwidth and thoughts of how it could be done were constantly in my mind.

Transmission of light through glass is an old, old idea. It had been used in past years to shine light for entertainment, for decoration, for short distances for surgery, through a glass rod, but it had not been possible to use it over the long distances required for telephony. Light passing through a rod of glass just fades out to nothing after a very short distance of a few feet. Efforts by many research laboratories to find a way to transmit light over long distances were desperate as the public, prompted by media reports of hopeful technical advances, were expecting more and more exotic services.

I played around with what was causing the failure of light to penetrate glass. With the invention of the laser in the 1950s and subsequent developments, there was an ideal source of light that could send out pulse of light in a digital stream of noughts and ones, represented by off and on states of the pulse.

Ideas do not always come in a flash, but by diligent trial-and-error experiments that take time and thought.

| Awards and Distinctions Received by Charles Kuen Kao |

| 1. Morey Award of the American Ceramic Society, in 1976. Citation: for outstanding contribution to glass science and technology. |

| 2. Stuart Ballantine Medal of the Franklin Institute, U.S.A., in 1977. Citation: for conceptual work on optical fiber communication systems. |

| 3. Rank Prize of Rank Trust Fund, U.K., in 1978. Citation: for pioneering work in optical fibre communication. |

| 4. Morris H. Liebmann Memorial Award of IEEE, U.S.A., in 1978. Citation: for making communication at optical frequencies practical by discovering, inventing, and developing the material, techniques and configurations for glass fiber waveguides and, in particular, for recognizing and proving by careful measurements in bulk glasses that silicon glass could provide the requisite low optical loss needed for a practical communication system. |

| 5. L.M. Ericsson International Prize of Ericsson Foundation, Sweden, in 1979. Citation: for fundamental contributions to the long distance transmission of information through optical fibers. |

| 6. Gold Medal of the Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association, U.S.A., in 1980. Citation: for contribution to the application of optical fiber technology to military communications. |

| 7. Alexander Graham Bell Medal of IEEE, U.S.A., in 1985. Citation: for pioneering contributions to optical fiber communications. |

| 8. Marconi International Fellowship of the Marconi Foundation, U.S.A., in 1985. Citation: for contributions toward a revolution in communication techniques in the form of optical fiber technology. |

| 9. Columbus Medal of the city of Genoa, Italy, in 1985. Citation: for significant scientific discovery. |

| 10. C & C Prize of the Foundation for Communication and Computer Promotion, Japan, in 1987. Citation: for pioneering work in optical fiber communication. |

| 11. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, of The Chinese University of Hong Kong, in 1985. Citation: for outstanding contributions to optical fibre communications. |

| 12. Faraday Medal of IEE, U.K., in 1989. Citation: for recognition of continuing outstanding work on optical communication including early work on establishing the 70 feasibility of optical fibre communication systems and defining the parameters involved. |

| 13. International Prize for New Materials of the American Physical Society, U.S.A., in 1989. Citation: for contribution to the materials research and development that resulted in practical low loss optical fibers, one of the cornerstones of optical communications technology. |

| 14. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, the University of Sussex, U.K., in 1990. Citation: for making important contributions to the understanding and application of opto-electronic techniques for communication. |

| 15. Degree of Honorary Doctor, Soka University, Japan, in 1991. Citation: for promoting science and culture. |

| 16. Doctor of Engineering, Honoris Causa, University of Glasgow, U.K., in 1992. Citation: for recognition of his achievements in the field of engineering. |

| 17. Gold Medal of The International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE), U.S.A., in 1992. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work and many contributions to the field of fiber optic communications. |

| 18. Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE), in 1993. Citation: for his distinguished academic career and his pioneering work on optical fibres |

| 19. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Durham, U.K., in 1994. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work in the field of telecommunications. |

| 20. Gold Medal of Engineering Excellence, of the World Federation of Engineering Organizations (WFEO), in 1995. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work and development in fiber optics which have deep significance for all mankind. |

| 21. Doctor of the University of Griffith University, Australia, in 1995. Citation: for recognition of his distinguished service to the world of international learning and university education. |

| 22. Japan Prize in the field of Information, Computer and Communication Systems, of The Science and Technology Foundation of Japan, in 1996. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering research on wide-band, low-loss optical fibre communications. |

| 23. Prince Philip Medal of the Royal Academy of Engineering, U.K., in 1996. Citation: in recognition of his pioneering contributions towards the invention of the optical fibre for telecommunications and for his leadership in its engineering and commercial realization; and for his distinguished contribution to higher education in Hong Kong. |

| 24. Doctor of Telecommunications Engineering, Honoris Causa, The University of Padova, Italy, in 1996. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work in the field of telecommunications engineering. |

| 25. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Hull, U.K., in 1998. |

| 26. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, Yale University, U.S.A., in 1999. Citation: for recognition of his achievements as an inventor and an educator. |

| 27. Charles Stark Draper Prize of the National Academy of Engineering, U.S.A., in 1999. Citation: for recognition of the conception and invention of optical fiber for communications and for the development of manufacturing processes that made the telecommunications revolution possible. |

| 28. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, The University of Greenwich, U.K., in 2002. |

| 29. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, Princeton University, U.S.A., in 2004. |

| 30. The Nobel Prize in Physics, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, Sweden, in 2009. Citation: for groundbreaking achievements concerning the transmission of light in fibers for optical communication. |

1. Much of the family information is reconstructed by Gwen Kao, based on her own knowledge and memories of Charles’ family background.

3. In modern pinyin Gao Chuiwan.

4. The Great Learning, the Doctrine of the Mean, the Analects of Confucius, and the Mencius were the core texts of Confucian learning.

6. The Chancellor being the Governor (after the resumption of sovereignty by China, the Chief Executive) serving in a largely ceremonial role.

7. Note added by Gwen Kao: In 2005, Alzheimer’s disease was confirmed, and at the moment there is no cure for it.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.