Arthur B. McDonald

Biographical

I was born in 1943 in Sydney, Nova Scotia, Canada, a city of about 30,000 people on Cape Breton Island. My mother’s and father’s families were Scottish and French settlers who had come to Atlantic Canada in the 1700s and early 1800s. My father was a Lieutenant in the Canadian Army and left for Europe when I was about a year old to participate in the battles related to the liberation of Holland. He received the Military Cross, one of the highest decorations for bravery and was wounded, returning to Canada in 1946. He and my mother were hard-working people who appreciated the value of a good education and encouraged me throughout my school days. I also had lots of support from my extended family and enjoyed my childhood, with a balanced mix of studies, fun, sports, family activities and work (I had a 104 house paper route that I remember as being almost all uphill, particularly in winter). My father was very active in the local community, serving as a City Councillor and together with my mother in many service and charitable organizations. I have one sister, ten years younger than I am, but we have a wonderful relationship in spite of the fact that I left home for university when she was just 7 years old.

Sydney was a great community in which to grow up, safe, social and supportive. I remember a positive educational environment in the schools, with many helpful teachers. I and a number of my classmates in high school were particularly influenced by Mr. Bob Chafe, our math teacher, who went out of his way to engage us in the subject, including extra classes going beyond the normal curriculum. A number of my classmates went on to careers in academia, including several mathematics professors.

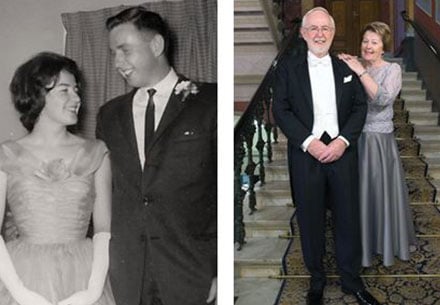

There was also a very healthy social environment in the community. I belonged to a service club for teenagers called HI-Y, associated with the local YMCA. This was the late 50s, Rock and Roll was King, and we had a dance for the boys and girls clubs on Friday nights after our meetings. Our clubs ran a community dance on Saturday night at the YMCA as a fund raiser for our service work. That was where I met my future wife, Janet, and I am very pleased to note that we will celebrate our 50th wedding anniversary in 2016. We have 4 children and 8 grandchildren who are a great joy to us. We have also loved to dance throughout our lives, undoubtedly because of our positive high school experience on the dance floor.

At the age of 17, I went to Dalhousie University in Halifax, 400 km away, to study Science, but with very little feeling for which area of Science I would like. I was strongly influenced again by my teachers, particularly Professor Ernie Guptill, my first year Physics teacher, who showed me how you could use mathematics to figure out how the world works in great detail. I also found that I was very good at solving physics problems and enjoyed doing so. These days when I am asked by young people how to choose what to follow as a career, I suggest that they try a number of areas to see which ones interest them and also to see which ones they are good at. The combination of those two features will enable them to have a successful career in an area where they are happy to go to work day after day. I feel that physics has been that way for me. I had my first experience of “engineering physics” by working in the summer for Prof. Ewart Blanchard, carefully measuring gravity on the roads of Nova Scotia, where we found an anomaly that was later developed into a profitable gypsum mine. I stayed at Dalhousie for my Master’s degree, working with Prof. Innes MacKenzie, studying the lifetimes of positrons in metals. A paper that arose from that work indicating the relationship of positron lifetimes to defects in materials is still one of my most highly cited papers. I spent one year obtaining a M.Sc. degree and then knew that I really wanted to be an experimental physicist.

As we were considering where to go for graduate school, my long-time friend, Peter Nicholson and I developed an idea that we put to the Department Chair at Dalhousie. We said that if he would sponsor a trip to potential graduate schools on the east coast of the US, we would take careful notes and provide a lecture and guide for other undergraduates considering where to apply. He agreed and we had a great time, visiting several of the Ivy League Schools among others. We then proceeded to apply to several of these schools for graduate study and were accepted but we were also accepted at CalTech and Stanford (Operations Research for Peter) and California just seemed like a great place to experience, so we accepted those offers.

CalTech was a marvellous experience. There was a Van de Graaff accelerator in the basement of the Kellogg Laboratory and we had as much beam time on that as we could want. My thesis supervisor, Prof. Charlie Barnes was an excellent mentor and very encouraging of the measurements that we wanted to pursue, using the nucleus to study fundamental symmetries and processes that could enable us to learn more about the basic laws of physics. I was very privileged to work with two close colleagues, Eric Adelberger and Hay Boon Mak. Eric went on to a very productive career in nuclear physics and in the study of the force of gravity at short distances with extremely beautiful and sophisticated experiments. Hay Boon became a Professor at Queen’s University, Kingston, Canada and made major contributions to parity violation measurements and the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory (SNO) project. At CalTech, we studied the properties of nuclear energy levels related to the symmetries of the Coulomb interaction, known as studies of Isospin Symmetry in nuclei.

Another interesting aspect of my time at CalTech (1965–69) was that I was working in the Kellogg laboratory headed by Prof. Willy Fowler, who later received the Nobel Prize in Physics for the understanding of how the elements are produced in the sun and other stars. It was an exciting place to be a graduate student as the latest developments in physics were the subject of discussion every day. Willy had a very sunny personality and there was a very collegial atmosphere in the laboratory. The seminars were at 7:30 pm on a Friday night, often followed by a party at one of the Professor’s houses. An Indication of Willy’s personality is the subtitle of his Nobel Lecture: “Ad astra per aspera et per ludum” that he translated as “To the stars through hard work and fun.” This is a spirit that I have always respected for research work, education and collegiality.

John Bahcall was a junior faculty member at CalTech when I was there and Ray Davis visited for several periods. They were working on the theory and experimental design for the measurement of neutrinos from the sun with Davis’ proposed large tank of cleaning fluid. Some of my fellow graduate students were measuring nuclear reactions related to neutrino detection in chlorine and this experiment was a big topic of conversation in the lab. The discrepancy observed between Davis’ experiment and Bahcall’s theory became known as The Solar Neutrino Problem and ultimately was the impetus for the establishment of the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory almost 20 years later. Ray received the Nobel Prize in 2002 for his pioneering work in solar neutrino detection.

Following CalTech, I accepted a postdoctoral position at Atomic Energy of Canada (AECL) Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories, working on basic research at the accelerator facility there in Doug Milton’s Nuclear Physics Branch. This was another very productive period with an in-house Tandem Van de Graaff accelerator, lots of beam time and very skilled colleagues. A year after I arrived, I obtained a permanent position there because a vacancy opened up as Dr. George Ewan moved to Queen’s University. After completing a series of measurements providing detailed information on isospin-forbidden decays in light nuclei at Chalk River, Princeton, Washington and Michigan State, Eric Adelberger and I published a paper concluding that the data was consistent with the effects expected from the basic Coulomb interaction with no evidence for any unusual distortions of this symmetry.

I then turned my interest to studies of parity violation in nuclei. One part of the Standard Electroweak Model associated with the exchange of neutral Z Bosons between quarks could only be probed effectively for up and down quarks, as the process was supressed for the other quarks. Therefore this process must be studied in weak interaction processes between quarks in nuclei where it is in competition with the strong interaction (about a million times stronger). The way to study the weak interaction in this case was to measure processes that violated parity symmetry. Basically we looked for the difference between a nuclear reaction and its mirror image. In most cases this would be expected to be a difference of only a part in a million, but in some nuclear processes it could be increased by factors of up to 1000 by the particular properties of nuclear levels.

During the 1970s I worked on a number of experiments of this nature with a number of collaborators, including a major experiment at Queen’s University involving many of the scientists who would eventually become colleagues on SNO. At Chalk River I concentrated finally on a measurement of parity violation in the disintegration of deuterium by circularly polarized gamma rays produced by a high intensity polarized electron beam. This experiment was carried out in collaboration with Dr. Davis Earle and formed the basis for our later long-time collaboration on SNO. The continuous-beam polarized electron source that we developed for this experiment was eventually transferred to the electron accelerator at MIT and used for further experiments by others there.

In 1982 I moved to Princeton University as a Full Professor and began work on polarized targets that were developed in collaboration with Prof. Will Happer, Prof. Frank Calaprice and Prof. Tim Chupp. The most interesting of these polarized targets with which I was associated was 3He polarized by spin transfer from optically polarized rubidium vapor. Through the development of samples at atmospheric pressure or greater, we extended the number of polarized nuclei by several orders of magnitude over previous techniques. This enabled a variety of experiments, including the use of polarized 3He to produce polarized epithermal neutrons for extensive measurements of parity violation in heavy nuclei at the Los Alamos spallation neutron facility. Following these initial developments, others used 3He polarized by this technique for a variety of nuclear and particle physics measurements and eventually for medical imaging.

In the summer of 1984, while at Chalk River finishing the analysis of our parity violation experiment, I became involved in the development of the SNO Collaboration, led by Herb Chen and George Ewan. Herb had an excellent idea for the resolution of the Solar Neutrino Problem if it was possible to borrow over 1000 tonnes of heavy water from Canada’s reserves. George had been seeking the best location for an underground laboratory as would be required for this measurement. Under their leadership, the original group of 16 collaboration members began work to develop a detector based on heavy water, to be sited underground and built with ultra-low radioactivity content.

It was a highly motivated group of scientists because we knew that the properties of deuterium in the heavy water could enable the simultaneous measurement of the electron flavor neutrinos produced in the sun and also the sum of all neutrino flavors. The comparison of these two measurements could provide a clear indication of whether any electron neutrinos had changed to another flavor before reaching our detector. However, the challenges associated with making these measurements were major, particularly with respect to restricting the radioactive gamma ray background that could break apart the deuterium leaving a free neutron, mimicking the second reaction that could be caused by any flavor of neutrino. The design had many challenges and required detailed simulation of the detector properties in order to be certain that it would be possible to observe both reactions.

I began work at Princeton on the measurement of radon gas emanated from materials and extracted from water. The tragedy of Herb’s death from leukemia in 1987 shocked and saddened us all, but we carried on, with George Ewan as Canadian spokesman and David Sinclair as UK Spokesman. I became the US Spokesman and was joined later in 1987 by Prof. Gene Beier of the University of Pennsylvania, an experienced neutrino physicist who had worked on the conversion of the Kamiokande detector to detect solar neutrinos. In 1988–89 I took a sabbatical year from Princeton at Queen’s University and worked with the international team on the development of a final design and detailed costing of the experiment for submission to the funding agencies in the three countries.

I was offered a faculty position at Queen’s University which I took up in the summer of 1989. Ironically, I was once again following in the footsteps of my long-time colleague and mentor, George Ewan, who was scheduled to retire several years later. I have often said that if you want a successful career in science, follow George Ewan’s lead. In December 1989 we received funding for the project from agencies in the three countries.

I became Director of the SNO Institute formed to take international responsibility for the project and also became Director of the international SNO Scientific Collaboration. By 1989, the collaboration had expanded to 14 institutions with a large number of experienced scientists and technical people with broad capabilities. The responsibility for various parts of the project had been accepted by groups within the collaboration, a number of our collaborators accepted responsibilities as Group Leaders and they carried out those responsibilities in a very dedicated way through the design, construction and operation of the project.

During the 1990s we followed our plans, overcame many obstacles by collaborative efforts and began data acquisition in 1999. Our first scientific results were published in 2001 and 2002. In those publications we demonstrated that we had in fact built the detector to meet the specifications that had been put forward in the 1980s. We had restricted the interfering radioactivity so that we could make accurate measurements of both of the reactions on deuterium that measured separately the number of electron neutrinos and the total number of all neutrino flavors reaching the detector from 8B decay in the sun. Our results showed that the calculations by Bahcall and others were very accurate for the initial rate of 8B electron neutrinos but that about two thirds of those neutrinos had changed into other active neutrino flavors (muon or tau) before reaching the detector. That conclusion was in agreement with the initial, less accurate results that we obtained by combining our results for electron neutrinos with the results of SuperKamiokande for solar neutrinos, where there is a small sensitivity for all neutrino flavors. We are honored to share the Nobel Prize with Prof. Kajita and the SuperKamiokande collaboration for their detailed measurements of atmospheric neutrinos and their observed decrease of the numbers of muon neutrinos while traversing the earth, explainable through the change of flavor of muon neutrinos.

These flavor changes for solar and atmospheric neutrinos could not occur unless the neutrinos have a non-zero mass. Those neutrino properties are outside the predictions of the Standard Model of Elementary particles and require extensions to that model. Finding those extensions that match the observed properties of neutrinos from these measurements and from the ever increasing number of new neutrino measurements will enable a fuller understanding of the laws of physics at a very fundamental level and an understanding of the many ways in which neutrino properties influence the evolution of our universe.

I was very fortunate to have such a dedicated and skilled group of colleagues, technical people and construction workers who worked wonders to build and operate a unique detector. When we obtained the data for neutrino interactions in our detector we were very satisfied to observe that the simulations that had been made back in 1987 were very accurate for the case where electron neutrinos were changing their flavor before reaching the earth. That meant that we had been able to accomplish the very stringent requirements that we had set for the project, including many aspects that had never been done before. It was a true team effort and I am very grateful to all members of the team and to their spouses and families that supported them throughout.

We were also very fortunate to receive strong international support from funding agencies, educational and research institutions, federal, provincial and local governments and the people of the Sudbury region who made us all feel at home there. We are also grateful to the management of AECL who arranged the loan of the heavy water and INCO/Vale who provided the underground location over many years, in what continues to be one of their most productive mines.

I truly enjoyed working with the SNO team and consider the very positive team effort on SNO to be a highlight of my many years of research in physics. Our results are significant for the basic understanding of neutrinos and that is what we set out to do, for some of us almost twenty years earlier. I am very pleased with the very large number of young people who had the opportunity to have a “Eureka” moment with us and who have gone on to productive careers beyond SNO. This was a very significant scientific result and a very substantial educational experience for all of us, with which I am very satisfied.

Curriculum vitae

Academic experience

| Position | Institution | Year |

| Professor Emeritus | Queen’s University | 2013–Present |

| Director | Sudbury Neutrino Observatory Collaboration | 1989–Present |

| Gordon and Patricia Gray Chair in Particle Astrophysics | Queen’s University | 2006–2013 |

| University Research Chair | Queen’s University | 2002–2006 |

| Director | SNO Institute | 1991–2003, 2006–2009 |

| Associate Director | SNOLAB Institute | 2009–2013 |

| Professor | Queen’s University | 1989–2013 |

| Professor | Princeton | 1982–1989 |

| Sr. Research Officer | Atomic Energy of Canada (Chalk River, Ontario) | 1980–1982 |

| Assoc. Research Officer | Chalk River | 1975–1980 |

| Assist. Research Officer | Chalk River | 1970–1975 |

| Postdoctoral Fellow | Chalk River | 1969–1970 |

Education

Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia – B.Sc. Physics (1964)

Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia – M.Sc. Physics (1965)

California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, USA – Ph.D. Physics (1969)

Awards

Governor General’s Gold Medal, Dalhousie, 1964

Rutherford Memorial Fellowship, (1969–1970)

Fellow of the American Physical Society, 1983

LL.D., honoris causa, Dalhousie, 1997

Fellow of Royal Society of Canada, 1997

Honorary Life Membership at Science North, Sudbury, Ontario, 1997

Killam Research Fellowship, 1998

LL.D., honoris causa, University College of Cape Breton, 1999

D. Sc., honoris causa, Royal Military College, 2001

T.W. Bonner Prize in Nuclear Physics from the American Physical Society, 2003

Canadian Association of Physicists Medal for Lifetime Achievement in Physics, 2003

Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada Award of Excellence, 2003

Gerhard Herzberg Canada Gold Medal for Science and Engineering, 2003

Sigma Xi Fund of Canada Award for Scientific Achievement, 2004

Bruno Pontecorvo Prize in Particle Physics, JINR, Dubna, 2005

D. Sc., honoris causa, University of Chicago, 2006

NSERC John C. Polanyi Award to the SNO team, 2006

Officer of the Order of Canada, 2006

Co-recipient, Benjamin Franklin Medal in Physics, 2007

LL.D., honoris causa, Saint Francis Xavier University, 2009

Fellow of the Royal Society of the UK and the Commonwealth, 2009

Member of Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame, 2009

Killam Prize in the Natural Sciences, 2010

Member of the Nova Scotia Discovery Centre Hall of Fame, 2010

D. Sc., honoris causa, University of Alberta, 2011

Henry Marshall Tory Medal, Royal Society of Canada, 2011

D. Sc., honoris causa, University of Waterloo, 2012

Member of the Order of Ontario, 2012

Co-recipient, European Physics Society HEP Division Giuseppe and Vanna Cocconi Prize, 2013

Co-recipient, Nobel Prize in Physics, 2015

Co-recipient, Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics (with the SNO Collaboration), 2015

Companion of the Order of Canada, 2015

Present memberships

| 1964–Present: | Member of Canadian Association of Physicists 1969– |

| Present: | Member of American Physical Society (Fellow 1983–present) |

| 1998–Present: | Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada |

| 2004–Present: | Member of the Professional Engineers of Ontario 2000– |

| Present: | CIAR Cosmology and Gravity Program Associate (Chair of the Advisory Board, 2000–05) |

| 2009–Present | Fellow of the Royal Society of the UK and the Commonwealth |

Visiting positions

CERN, Geneva (2004), University of Hawaii (2004, 2009), Affiliate Graduate Faculty, University of Hawaii (2010–), Oxford University (2003, 2009), University of Washington, Seattle (1978), Los Alamos National Laboratory (1981), Queen’s University (1988)

Personal

Citizenship: Canadian

Married (four children, eight grandchildren)

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and later published in the book series Les Prix Nobel/ Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes. The information is sometimes updated with an addendum submitted by the Laureate.

Nobel Prize announcements 2025

This year’s Nobel Prize announcements will take place 6–13 October. All announcements will be streamed live here on nobelprize.org.