“I really recommend that young people do things that they like”

Interview with Syukuro Manabe, March 2022

We met and interviewed physics laureate Suki Manabe on 16 March, 2022. We spoke about his endless curiosity, valuable life advice and the topic he has researched for the last six decades – climate change.

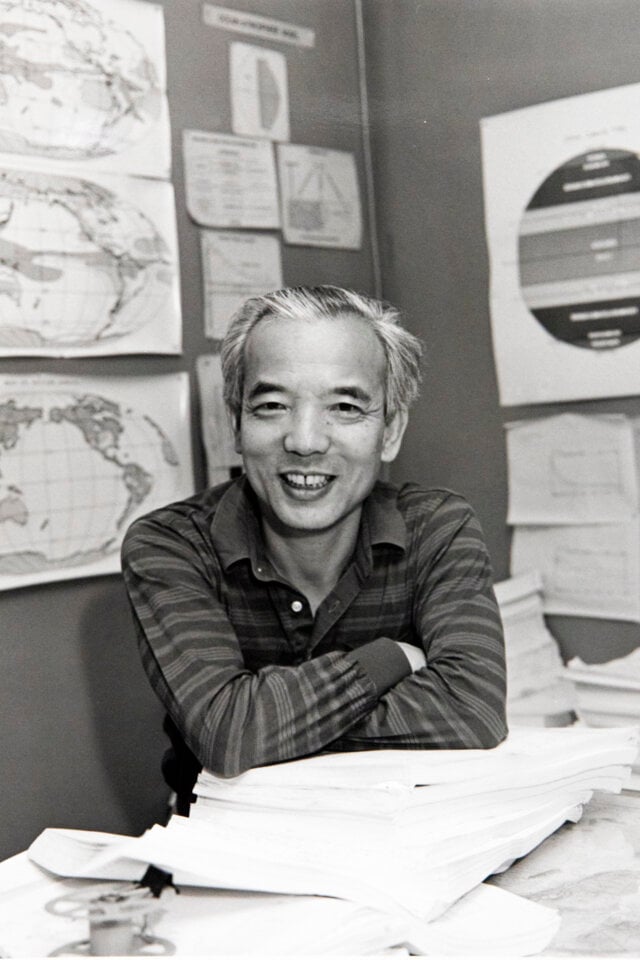

Syukuro Manabe, 1997.

Photo: Princeton University, Office of Communications, Robert P. Matthews (1997)

I wanted to start off by asking where your passion for science comes from?

Suki Manabe: I guess that when I was little, I really liked to look at the sky and daydream. I was interested in weather and the climate is sort of the average of weather. In a sense, I think my curiosity about weather and climate started when I was very little.

Would you say that there was a particular person, a role model, a parent, or a teacher that encouraged this curiosity in some way?

I’m not sure, but I was a little bit of an unsociable kind of person. When I was in elementary school, I usually stayed at home, laid down and thought about something endlessly. I don’t think this is a good personal characteristic for some professions. But in my profession, it has been a very good personal trait, which I think has shaped my career as a research scientist. This personality, which is a shortcoming for most professions, has been good for me.

Would you say that daydreaming about science is something that you still do?

That is right. I think about the same things day after day and I try to understand them but I can’t. I keep on day dreaming, thinking about the same things again and again and again. That has turned out to be a very important factor for my success as a scientist.

Is that something you would say is a quality that successful scientists need? What other qualities do you think you need to become a successful scientist?

I guess that one of the things is curiosity. You are curious about something and then you think about why this is happening. That is what happened to me with climate change, which I have been working with for the last six decades. It’s a long time. This turned out to be a very fun thing to think about because, as you know, daily weather is very interesting. Why is the climate changing? Why is the climate changing the way it does? And what is controlling that change? I have always been interested in climate change such as global warming. I am also interested in why the ice age happened and why the climate was so warm when dinosaurs were living on this planet. It looks as if carbon dioxide is one of the important factors. I have been doing this driven by curiosity: why is our climate changing the way it does? I think this also helped me in my career. I’m curious about it. I was doing it not because climate change is very important for human beings. I never had that slightest idea climate was going to be so important when I was studying it in the 1960s. I never had the slightest idea that climate change was going to be such an important factor for human beings. What drove me was pure curiosity.

You’ve been working with the issue of climate change for six decades, what are your thoughts about climate change today? Do you have a message that you would like to share?

When we talk about current climate change, which we are right in the middle of, we mainly think about temperature. But what is happening now is that the temperature change on this planet has affected the global water cycle – distribution of precipitation, distribution of evaporation from the continent. It has a profound effect on the water cycle of this planet. That is one of the reasons why we get droughts more and more frequently. For example in the sub-Saharan region in Africa, Sahel, I think that this change, which is ongoing, is starting to have a profound effect on our daily lives. This is why climate change has become such an important phenomenon. What is happening is that we are burning fossil fuels at a tremendous speed. We are burning coal, which has accumulated over a few hundred million years, in a few centuries instead of a few hundred million years. That is why the climate is changing so rapidly and posing profound problems for us.

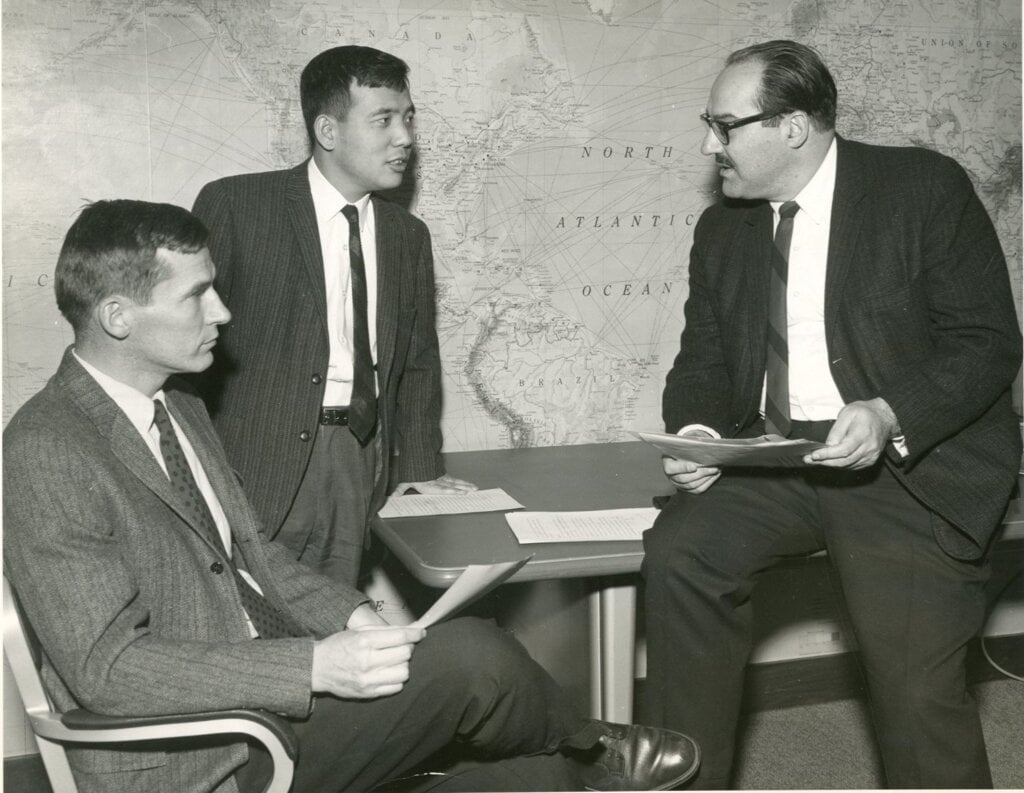

Syukuro Manabe (center) speaks with colleagues Kirk Bryan and Joseph Smagorinksy at Princeton University in 1969.

Photo courtesy of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (GFDL)

You are born in Japan but you have lived in the US for many years. How was that journey from Japan to the US?

You know, the Japanese people always worry about each other – they don’t want to hurt each other’s feelings. So for example, Japanese people don’t want to say no. So even though your answer is no, you try very hard to moderate the impact of saying no to another person listening to you. In science this is not a very good thing, you have to say very clearly you disagree with each other. Then you think about how we disagree. Why do we disagree? In order to tell him I’m right and to prove that I’m right, you have to do additional research. What is that research? The other person also thinks about why we disagree with each other in order to prove he is right. What kind of result do you have to present to prove you are right? So in a sense, by disagreeing, both gain greatly and make good progress to understand the problem which we are tackling. When I came to the US, I found out that people can disagree openly in public. I thought this was a great thing. Of course, Japanese people are trying to think about each other, and that’s wonderful and that’s why they are successful. We live together harmoniously because of this trait. But, in a sense, I like the way things are done in the US.

How do you think that we can encourage more women and more diversity in science?

I think this is very important. Women are half of our population, right? I think female scientists, even though they are very capable of doing a great job and getting married and having children, many of them stop doing research at that point. What is very important is to have more daycare centers so that they can put their children in daycare. I think more countries should invest more money in daycare, it is very important. You could give financial support for families who have more children. I would like to have every country in the world do that; to put more emphasis on these activities.

How did you celebrate the news of the prize? How did you react when you got the news?

I have to say it was a big surprise because I never expected to receive it. It was a kind of shock to me and for five months after the announcement of the Nobel Prize, this news has gradually sunk in. Nobody doing the kind of work I was doing has got this prize. Almost everybody who got a prize got it for contributions for the advancement of modern physics, quantum mechanics and so forth. Nobody got this award for climate research before. But I am very grateful that the Swedish Academy of Sciences thought about giving me the prize. You know, I am 90 years old so at this age, I will die happily knowing that I got a Nobel Prize in Physics. It’s gradually sinking in and now finally I can relax and begin to think about reading a book which I never had the time to do before.

Princeton University senior meteorologist and 2021 Nobel Prize laureate Syukuro Manabe celebrates with students, faculty and staff at a reception in his honor on the Princeton campus on Oct. 5.

Photo: Princeton University, Office of Communications, Denise Applewhite (2021)

You turned 90 years old last year, what life advice would you give to a young person?

Looking back at the last six decades of my career, I really enjoyed what I was doing and being curious. I liked what I was doing and digging deeper and deeper. Sometimes it was just a struggle to get through but looking back, it is a nice memory. I have enjoyed my life exploring the secret of climate change. The most important reason is; I was doing what I like most and probably what I was best suited to doing, as I explained at the beginning. There is a saying that what one likes one does well, so I would like to have young people do what they like in their life. I think when young people do what they like they usually do well. When you get more and more involved you enjoy it more and dig deeper. I really recommend that young people do things that they like and have a great life.

Syukuro Manabe, photographed following the announcement of the Nobel Prize in Physics 2021.

Photographer: Nobuko Manabe

How do you like to spend your spare time?

To be honest with you, I spent a major fraction of my life thinking about the same thing. I really didn’t do much else. Now at 90, I finally decided to stop doing active research. What I’m thinking now is to read a book about something which I never had time to read, I was too busy all the time. One of the topics I’m reading is how this planet evolved during the last four and half billion years and how life evolved starting from phytoplankton. Then more animals started developing and then us human beings. That is one topic I’m interested in reading about. At night, sometimes I want to relax more. I’m looking for some books. My wife has many books written in Japanese so I think I will start reading some of those. That’s how I want to spend my life.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

First published: March 2022

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 14 laureates' work and discoveries range from quantum tunnelling to promoting democratic rights.

See them all presented here.