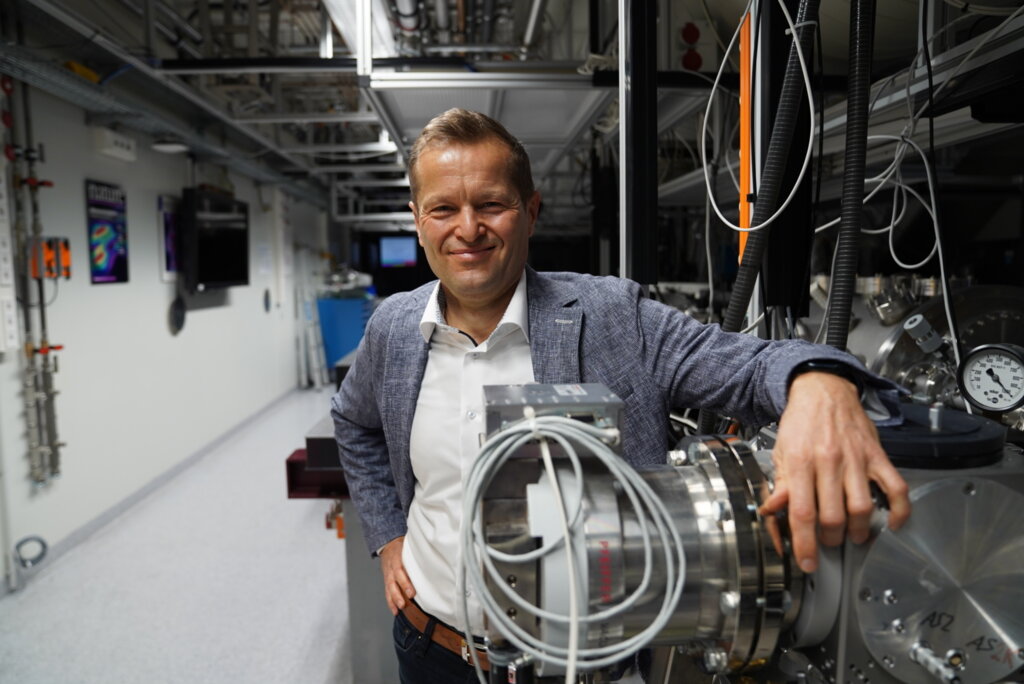

Ferenc Krausz

Podcast

Nobel Prize Conversations

“I think science, like sports and culture, can play a really unique role to bring together different nations, bring together different cultures, disassemble boundaries and borders between countries, between different cultures. I think science can make a huge contribution there”

Meet 2023 physics laureate Ferenc Krausz in an in-depth conversation with podcast host Adam Smith. Krausz tells us about his scientific journey which has encompassed three countries, and to which he attributes his Nobel Prize.

Krausz was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for giving humanity new tools to exploring the world of electrons inside atoms and molecules. In this podcast, he tells us about how this moment was a long time in the making: ”These particles were discovered more than a hundred years before. It took an utter century to develop the tools to actually capture them in motion. It was an indescribable moment.”

This conversation was published on 30 May, 2024. The host of this podcast is nobelprize.org’s Adam Smith, joined by Clare Brilliant.

Below you find a transcript of the podcast interview. The transcript was created using speech recognition software. While it has been reviewed by human transcribers, it may contain errors.

MUSIC

Ferenc Krausz: Wow. These particles were discovered more than a hundred years before. It took an utter century to develop the tools to actually capture them in motion. It was an indescribable moment.

Adam Smith: Listening to Ferenc Krausz, it’s really obvious how incredibly excited he is by the science, and that’s lovely. That excitement extends to not just his experiments and his discoveries, but then applying those discoveries or getting engaged in humanitarian work. He seems to be somebody who just gets on and gets things done, doesn’t faff about. He also feels very strongly the need to be an internationalist. I suppose it’s partly a result of him being the product of more than one country, scientifically. But he is intent on using science to forge international connections. That’s a very important message in this day and age, particularly, I suppose, when many people are becoming more nationalist in their outlook. There are many reasons to engage with Ferenc Krausz, and what he has to say. I hope you enjoy this conversation.

MUSIC

Clare Brilliant: This is Nobel Prize Conversations. Our guest is Ferenc Krausz, the 2023 physics laureate. He was awarded the prize for experimental methods that generate attosecond pulses of light for the study of electron dynamics in matter. He shared the prize with Anne L’Huillier and Pierre Agostini. Your host is Adam Smith, Chief Scientific Officer at Nobel Prize Outreach. This podcast was produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Ferenc Krausz is director of the Max Plank Institute of Quantum Optics in Garing, Germany, and a professor at Ludwig Maximillians University in Munich. He speaks to Adam about being molded by the education systems of three different countries, donating his prize money and how a potentially life-saving test for early stage cancer and Alzheimer’s started with basic curiosity in the lab. But first, imagine taking a tour of the Max Plank Institute from a brand new Nobel Prize laureate.

Smith: When we spoke on 3 October, just a few minutes after you’d learnt that you’d been awarded the prize, I got the impression then that you are a very conscientious person because you were planning that afternoon to do a public tour of your institute. I think you went ahead and did it even though you’d just received the news and there was so much demand on your time, you still fulfilled your duties and did the public tour. Is that right?

Krausz: Just right. But I wouldn’t say that I considered this as a duty. I would say, this was a great deal of pleasure for me. Of course, this announcement made it obviously very special when I arrived at the institute, actually this was just a couple of minutes after their announcement. When I arrived here, people obviously knew already and they were smiling at me and taking photographs. Very quickly, obviously the news spread here on the campus. This was kind of an open day also at other institutes, research institutes here at the campus. Obviously the news did attract quite some number of interested people. I had the chance to actually give a talk to them. This was what I was preparing at home when I got the call. It was a very special experience. I didn’t consider this as a duty, but it was really a very special experience, certainly once for a lifetime experience.

Smith: Something else we spoke about on that very brief call was the fact that just the day before Katalin Karikó had been awarded the Nobel Prize. You were the second Hungarian in two days, and you didn’t know each other before, but you said then you were looking forward to meeting and talking. I imagine that happened in Stockholm when you were together there in December.

Krausz: This happened already before, both of us were invited by the President of Hungary to a reception a couple of weeks after the announcement. We had a chance to meet each other already there. I can always say that Katalin is, as a human being, as unique as she’s as a scientist. It was a fantastic experience for me to meet her, such an incredibly modest person after what she achieved. With her invention she saved a really uncountable number of lives over just the last couple of years. I have the highest possible regards for her. This is another hearty benefit from receiving such a prize that I had the pleasure to meet her and to get to know her so closely.

Smith: Yes. I imagine you must have met all sorts of people who you never thought you would encounter before. Is there one who stands out, one person who you’ve bumped into because of the prize that has stuck in your memory?

Krausz: There are too many to actually, I think it would be almost unfair to mention one, because there have been so many whom I probably would’ve never met in that way or never met in any way otherwise, including ministers, outstanding world-renowned scientists from other areas of science. One example was of course the chair of the Swedish parliament, whom I had the pleasure to meet actually in the reception of the Hungarian embassy in Stockholm. The biggest highlight was to meet the queen and the king, no question. It was an incredible experience to actually even have the chance to talk to them, even quite extensively. It was a fantastic experience.

Smith: Of course, on the theme of being a Hungarian scientist. Of course, there have been many Hungarians awarded the Nobel Prize. It’s obviously very important to you to be a Hungarian scientist, and it’s important to Hungary. I’m interested how you think about that in the context of the international nature of science and how really science is, as you yourself, emphasise a very international effort.

Krausz: Actually, I feel very privileged that this still unbelievable recognition of my work by the Nobel Prize is something that I can give back to three countries, not just one, to Hungary, to Austria and to Germany. Each time, whenever I’m asked about this, I emphasise that I, from the deepest of my heart, feel that all three countries deserve this to the same extent. From Hungary, I received my whole education and eventually even the first impulses to move in this direction, to get interested in lasers, ultra short pulse, physics, and get interested even in science and in research at all. In Austria, I had fantastic years, where I had freedom to do what I was interested in. Eventually we managed with a very small team to actually perform the experiments that obviously were considered to be worthy of such a recognition. The third phase of my professional career so far, and has been meanwhile, about 20 years in Germany, where we had just unparalleled opportunities and possibilities to expand the field and to help the field proliferate because I think most discoveries, however exciting they might appear, would not deserve such a recognition, if not very many others in the world get interested and utilise the new opportunities that particular discovery opened up. I think, here at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and the Ludwig-Maximilian University, we did have the chance to actually build up this family, the atto work family, like hundred people with whom we not just have the chance to perform fantastic experiments here under ideal conditions. But we also had the chance to actually build collaborations towards all directions, literally all directions, collaborations with groups from the US, from other European countries, from Japan, from Korea, from China. So we also forced the proliferation of the technology. Actually, we have played a very active role to create the very first attosecond laboratory of the Arabic world in Riyadh in Saudi Arabia, which we opened in 2013. I have to say, I’m very proud of this because in that area of our planet, this field just was not present at all and we created it. In this laboratory, really great results were achieved, which were published in the best journals of the world. This was very important.

Smith: I think it’s really important to discuss this because again, the sort of snapshot view of you is a Hungarian scientist and great for Hungary, but the way you draw that out into a scientist who works across borders within the heart of Europe and see things in such an international sense, and it’s all about coming together, is the absolute opposite of the sort of rise of nationalism that one sees in so many places, rather worryingly now, there’s a very important message there.

Krausz: Absolutely. I think science, like sports and culture, can play a really unique role to bring together different nations, bring together different cultures, disassemble boundaries and borders between countries, between different cultures. I think science can make a huge contribution there. Great contribution.

Smith: In fact, on that subject, you and your colleagues in the attosecond lab have begun this charity called Science for People, which helps, I think mostly young people in Ukraine get access to education when education has been disrupted. Is that right?

Krausz: That is correct. The story goes back basically to the early days after the war in Ukraine broke out. I used to be in Budapest frequently in the framework of a big project that we are running there. It was a completely different perspective, the war, just in a neighboring country, it’s kind of amazing how differently it feels, even just slightly farther away. Germany is not that dramatically farther away, but far enough to feel this completely differently if one is there in that very country, which is directly neighboring the country where there is war. Just directly from that country, 10,000 people crossed the border day by day. One is watching that on television, then the feeling is coming, wow, one has to do something. I mean, do we have to help these people?

My first thought was, okay, I go just to the border and also volunteer some help. But I recognised very quickly that my countryman did a fantastic job there, and I could do only an infinite improvement if I would be even needed. It looked like on television, there was not even a need because there were many there. I continued thinking, what is I could do? So the idea came up. While I do have a scientific network, which is already quite broad, I do know many scientists all over the world, far away from Germany, far away from Ukraine, where probably if the difference between looking at this war in Ukraine is so big between being in Hungary and being in Germany, then how big the difference can be if someone in the United States, in Canada, in Australia, wherever. I mean this is just like, wow, this is not my problem.

Maybe occasionally one gets some message about that in the news, but that’s it. I thought, well, I have to send a national network so I could utilise this to actually sensitise, these people that something is going on here, which is very bad. Of course, it’s bad because people are being killed, day by day, but it’s bad for a completely different reason, which may not be our first thought in the context of a war, namely, what about the children, right? One can think about what is the responsibility of the adults to have elected a certain president in one country or the other, and therefore they somehow are to be blamed to some extent. But for sure, this certainly cannot apply to the children. I mean, they are completely innocent and they suffer most. If this is going on, then they are just deprived of their future. Schools are closed down, they cannot go to school. They just are enforced to stay at home. They often don’t have even connections to their fellow students. Of course, they cannot develop as a normal child is supposed to at that age. This was a huge concern for me, what we could possibly do for them. I thought, well, I think this is a topic that is probably suitable to sensitise the scientific community with it, and that’s what I try to do.

Smith: How do you actually do that? How do you bring the scientific community into the picture?

Krausz: Yeah, first of all, of course, we have created our organisation. It was important to have that kind of legal basis. This was one thing and quite a few colleagues here at attoworld volunteered to support me. It’s really a fantastic team here. Up to someone, like a dozen people who are involved in this organisation and do basically almost it on a daily basis to work for it, of course, without getting paid for that at all. Simultaneously I just contacted several hundred scientists all over the world, via email explaining them what we are doing, what to try to do, and that we need their help and any donation, even 10 euro or 10 dollars would help us any small amount, because it is so incredibly valuable in a country like Ukraine at the moment.

That’s how it started. Then I happened to win one or the other prize even before the Nobel Prize, the Wolf Prize and the Frontiers of Knowledge Award, both also accompanied by quite a significant amount of monetary part, which I more or less completely channeled into this organisation in both cases. This then created a basis on which we could start operating. We teamed up with an organisation in Ukraine because we are not there and we cannot define the best possible way, the need, where is the biggest need and in cooperation with this organisation, then we have undertaken quite a number of actions.

Smith: We should just dwell on that point, that not only having the energy and desire to set this up, but also donating your prize monies to, it’s a major help. I would imagine it’s quite something to have done.

Krausz: It is particularly motivating to see how little funding, how big difference can make under the current circumstances. Now, just think of our current program, which we started just a few months ago, where we encouraged the teachers from different schools to actually participate in a tutoring program in the framework of which they would deal with either children who are kind of lagging behind. There are many, not just in Ukraine, even in Europe, of course there is many. There are also children who are excellent and who would like to learn even more than they can do at school. Basically both types. And very quickly we started two schools, couple of those in teachers. We pay the teachers for providing this private tutoring. This is a great help for the teacher because they are very ill paid.

This is certainly an additional big incentive for them to actually not start considering maybe moving away from the country, but staying there, dealing with the children. I think this is one big benefit. The other thing is, of course, this auxiliary additional education is free for the children, and there was a very positive response. Step by step, we now extend this. Currently four schools are involved, one of them actually close to the frontline, close to the Dnepr river. We are now about to actually extend it to more and more schools, depending on the influx of donations.

Smith: Goodness. Given your Wolf Prize money and your BBVA prize money is already a huge undertaking. Am I right in thinking that you also gave some of your Nobel Prize money?

Krausz: This is correct significant section of that is also not now in one step, but it’s kind of being transferred step by step in the next couple of years, right?

Smith: That’s extremely generous. Is this something that can be extended to other countries? Because I imagine now that the network of scientists, as we were saying earlier, it extends internationally. Of course there are so many, sadly, crisis situations where the children especially are suffering. Can you see this becoming an organisation which steps in to try and provide assistance with partners in, for instance, Gaza or Sudan or wherever?

Krausz: Absolutely. I do fully agree with you that unfortunately Ukraine is not the only region in the world where such a help, such a support is badly needed due to our very limited resources. I think we cannot diversify towards more crisis regions at the moment, without taking the risk that we are becoming under-critical. For sure it would be most desirable to actually scale this organisation towards really international scale, with several locations where it’s operating. We’ll have to see. In so many cases, it depends on individuals, right? Whether there are individuals out there who are not only willing to occasionally donate a little bit of money, which is already a huge help. We are incredibly grateful to all of them, but do much more. It is much more, of course, to actually say, okay, now I will also take action. Of course, that requires a big discussion for yourself. Are you willing to actually spend a significant fraction of your efforts, time and energy on such a course?

Smith: Yes. It strikes me that you really have tapped into something very exciting and powerful, which is this network of scientists who already talk to each other, who already work together, who already know that they can have very robust conversations and get things done. Often working through difficult circumstances. I can’t imagine that it was particularly easy to set up an at second lab in Riyadh, but people work together and they get through the problems. With that resource behind you, I can see that that’s something to treasure and to nurture and more could be done.

Krausz: Absolutely.

Smith: It’s a little difficult territory. Can I ask where the responsibilities as scientists you think sort of lie and stop, because this is the provision of help to those who are in desperate need of help, in this case, in desperate need of education. How far would you go as scientists in feeling that it was your responsibility to get involved? For instance, in politics, we were discussing a little earlier the rise of nationalism. How much is it a scientist’s job, do you think to step into that arena? Not specifically that question, but the political arena?

Krausz: This is a very good question and a very difficult question. At the same time, I personally feel that not just scientists, but we as a society do have the responsibility to speak out if we have the feeling that something develops in the wrong direction. I wouldn’t say that this is now a specific responsibility of scientists. I think lawyers, medical doctors, engineers, and all others you name, are actually challenged to undertake something, if necessary, go to the street and protest and make sure that their voice is being heard. In the particular case of science, I would feel that the particular responsibility of scientists lie in the context of challenges that humankind, these days for quite a while where science can do a lot, science can explore the reality to make sure that politicians are in a position to make important decisions about the future, which can affect the future of humankind, and not on the basis of assumptions, but on the basis of facts, scientific facts in the context of the degradation of biodiversity in the context of the climate change, to name just two major examples, right?

Unfortunately, we do hear almost on a daily basis that politicians with greatest influence, question the role of humans in the climate change. These are the things where I do see scientists to have an incredible responsibility. Here, we have to try to find all possible channels and all possible ways to actually make clear that this is nonsense. This is nonsense to question the role of humanity in the current situation.

Smith: Of course, the problem is that nobody likes to be told they’re speaking nonsense. It’s a question of finding ways to engage people to become more evidence-based in their thinking. To become better at app praising evidence. It’s a long task.

MUSIC

Smith: Can you take us back to that moment and tell us what it felt like in the lab to be the very first to achieve this goal, which was at that point, I believe, just a curiosity-driven goal. You just wanted to do it because it was something you were fascinated by.

Krausz: You have put it so beautifully that I almost don’t like to comment even on it, because you actually said what I wanted to say. I and my colleagues were driven purely by curiosity, be able to reach out to somewhere where humans couldn’t reach out before, to see how these electrons actually move within a molecule. In that moment when one sees this for the first time, first thoughts are like, wow, these particles, these elementary particles, the electrons were discovered more than a hundred years before. It took another century to develop the tools to actually capture them in motion. It was an indescribable moment, when one feels that there is just no effort, which would not be worth this. This is actually also my main conclusion for young scientists. I’ve been often asked over the past few weeks and months, what is my advice and what is my message to young people who are possibly considering to move into science and to become a scientist, a researcher? And I used to say, well, you should just ask yourself what the feeling could possibly be that you are seeing something which no one has seen before. We have here another eight billion people living on this planet. You just see something when you know, okay, I’m the first one who is seeing this and maybe start thinking what this could be good for. This is just indescribable. And this provides you with such a motivation to really overcome all obstacles.

Smith: Getting to the point in 2001 where you achieved the goal is a very long haul, and there must have been so many setbacks along the way. What is it that drives you? Is it the little observations along the way, the answers to the smaller questions you ask that just keeps you going and keeps it building. If you like, where did it start and how did it not die? That curiosity?

Krausz: A very good question. I think humankind deserves this. Actually the scientific community and our culture in science as it grew over the decades and even centuries, I think deserves a big credit here, very clever construction, that even if you set yourself a goal, which may be a very bold one, a very big one, so that it takes you 10 years or more to reach it, if you can reach it at all. Even then there is of course many small incremental steps towards that goal where it’s absolutely your good, right? It’s absolutely expected and accepted that you also share these incremental steps forward with the scientific community in form of scientific publications. Perhaps it is even underestimated but this of course, plays an extremely important role to actually keep all the people who are supposed to contribute to such a feat to be eventually achieved, keep them motivated all the time, right?

Because we human beings are not very different in certain properties from a dog. A dog also likes to serve you if you reward it, right? That’s how you train it actually. That’s how you make it do things. You would like it to do that you always reward it. We, human beings, also like to be rewarded with all our efforts and these publications on the way are our rewards. Which gives us, again, a lot of positive strength and energy to try to take the next step. I think it’s quite easy. It’s so trivial that we don’t even think of it, right? It’s just works, right?

Smith: I love that the scientific method just works.

MUSIC

Brilliant: Adam, what is an attosecond light pulse? How short is it?

Smith: How short is an attosecond? Okay. It is naught 0.0000000000000001 seconds.

Brilliant: How on earth can we picture in our heads what that means?

Smith: It’s the time that it takes light to travel three angstroms, which is about the width of an atom. Apparently there are about as many attosecond in a second as there have been seconds in the age of the universe.

Brilliant: That’s incredible. The mind boggles at something that’s so short.

Smith: Yes. That’s only an approximation, not precise. Basically I think the answer is it’s pretty much impossible to picture something so short. It’s just really short.

Brilliant: How does an attosecond relate to Ferenc Krausz’ work?

Smith: He and his lab were working to create the shortest possible light pulses, and it’s intellectually and technically incredibly difficult to do this, but his lab was the first to make an attosecond light pulse, which lasted hundreds of attosecond, and now they produce light pulses also in the region of tens of attosecond. It’s the ability to actually produce an attosecond light pulse that was behind the award of Ferenc Krausz’ Nobel Prize.

Brilliant: You talked about that euphoric moment when they realised they could do this. Why is it so important?

Smith: There was this race to, if you like, a race to the bottom, to the shortest to see who could do it, and they did it. It’s important because it allows you to see things that could not be seen clearly before. Have you ever seen those pictures of moments frozen in time that were very popular a while ago? I don’t know whether people still look at them. There’s a particular image of a bullet traveling through an apple.

Brilliant: Yes. I think I know what you mean. Yes.

Smith: You see the bursting apple and the bullet frozen in time.

Brilliant: Yes.

Smith: That image, and many like it were made by a man at MIT called Harold Edgerton, who had developed new methods of photography using strobe lighting and things. The attosecond light pulse allows you to do a very similar thing at just a much shorter timescale. It allows you to look at things occurring in the attosecond timeframe, which include, for instance, the transfer of electrons between energy levels or the transfer of electrons between atoms in a chemical reaction. You can picture all sorts of things that were just invisible before.

Brilliant: Presumably it’s helping us to understand a lot more about molecular physics. What other applications does it have?

Smith: It’s important for understanding probably pretty much everything because everything boils down to the movement of subatomic particles, which can now be seen. But it’s had particular applications in electronic circuitry where you can see the propagation of information in electronic circuits. Also these days it’s being applied to medicine.

Brilliant: That seems quite a leap to me. How can you go from this to medical applications?

Smith: I asked Ferenc Krausz how you would apply these light pulses to the study of, for instance, the early stages of disease. Let’s listen.

MUSIC

Smith: The pulses that you have been able to produce allow us to visualise, allow scientists to visualise the world of the electron, but you have now taken it a step further and you are using it as a diagnostic tool. These are real world applications. It’s really the stuff of science fiction, if you like, that you can use them to discover molecular fingerprints of disease. Do tell us please how it works.

Krausz: Before I would try to tell you, let me just emphasise something which I think very important and goes way beyond the actual method that you asked me about. It is the impossibility to actually predict what a discovery in basic science will eventually be good for. We would have had no chance to, even if someone instructs us now to sit down and think as long as you need to think, to come up with the idea that attosecond technology one day will offer a method for extracting sizable information from a human blood sample about the health state of the individual. No way. This is what happened 15 years later. I think this shows how big the responsibility of governments is to provide a decent funding for basic science without asking scientists too many questions about what will be this good for. Of course, if they will be asked and enforced to say something, they will always say something, but later on they will recognise that they were completely wrong because what they have discovered will be good for something completely different, which they could not foresee. I think my big advice to the political leadership of all those countries who can afford, who are in a fortunate position to be able to afford funding science at a decent level should never underestimate the importance of basic science and should always provide a very decent fraction of the total amount of the money available for funding science for basic science. This sooner or later will be reported, and I think here we can deliver a great example. 15 years later, the application came up, which just could not be foreseen. The application is as follows. We take a very brief single cycle infrared laser pulse consisting of one single oscillation cycle of the electric and expose a human blood plasma sample to this pulse.

This incredibly fast excitation brings all essentially all the molecules in this blood sample, all the billions of molecules or trillions, we don’t need to know how many molecules into vibration. These vibrating molecules also do emit coherent light in the wake of the excitation. This ultra short infrared pulse is irradiated in the sample in a well coated field. Behind this very short flesh of infrared light, actually a radiation is emitted by the sample by the excited blood sample, which we can capture and sample with attosecond technology. The oscillating electric field of the signal coming from the molecules, if you like, the sound of molecules we can capture with attosecond technology. The sound of molecules tells us a lot about the molecules themselves, because different molecules emit different sounds at different frequencies. That’s an incredible amount of information which we now can capture with attosecond technology.

As opposed to other techniques like mass spectrometry, we can’t identify the individual molecules in such a complex sample containing an unknown number of different types of molecules. Certainly more than 100,000 different types of molecules that we can’t do. But what we can do is we can capture the overall information coming, basically the voices of all these molecules and we can look whether this overall signal, which we call the infrared fingerprint of this blood sample, whether this shows any correlation to unfolding diseases. First of all, we have to establish how this signal is supposed to look like for healthy individuals, and our organism is complex enough that even as a healthy person, we are different and therefore our infrared fingerprints are also different. Just like our real fingerprints are, each and every individual has a different infrared fingerprint. This is what we have to measure initially.

Ideally, whilst we are healthy, this is our healthy baseline. From then on, we just need to follow up the individuals and see when actually the infra fingerprint starts deviating from their own healthy baseline, the individual baseline, and then ask what this may be due to. To figure out what this may be due to. We can do so-called cross-sectional studies case cultural studies where we select people with a certain physiological condition like lung cancer and health individuals to figure out whether lung cancer causes a certain definite pattern in this infrared fingerprint that we can assign to this disease. This we can do, of course, in other case control studies for other diseases, all types of different cancer. We have done this already for eight different types of cancer, but we can do this also for cardiovascular diseases, for diabetes and so on. In all cases that we have looked at so far, we have found a specific characteristic inherent pattern that is specific to that disease.

Smith: Gosh. So different diseases affect, if you like, the pitch of the voices of the molecules in different ways. They sing a slightly different song.

Krausz: Not the voice of the molecules. They affect different ways, but they change the molecule composition of human blood. This may be still the same molecules, but certain types of molecules have become more abundant. Other types become less abundant if some disease starts unfolding. This of course will change the overall signal.

Smith: Your spotting changes in the molecular composition of the plasma sample.

Krausz: Precisely.

Smith: The subtlety is that you can detect molecular changes in the composition that are tied to specific diseases.

Krausz: Exactly. This is a paradigm change in biomarker research.

Smith: Absolutely.

Krausz: Biomarker research so far has been about trying to identify the needle in the haystack, right? To pick out those individual molecules, which out of the 100,000 different molecules in human blood, which sensitively respond to the appearance of a certain abnormality. But not only that, this is the easier part, the more difficult part is to pick out those molecules which respond only to this disease. Unfortunately, the main reason for the failure of many biomarker projects is, um, due to the second part. It’s relatively easy to identify molecules which respond to a certain physiological condition in the body. It is extremely difficult to find some which responds only to that very condition and doesn’t respond to other ones.

Smith: Absolutely. The power and implications of what you are doing are enormous. Imagine if you could, for instance, produce an early fingerprint for the onset of dementia for Alzheimer’s disease or something like that, it would be of course hugely beneficial to medical research, but it would also have profound implications for the insurance industry and people’s general wellbeing.

Krausz: Absolutely. You mentioned an excellent example. We just had a very exciting scientific discussion with a colleague from another German university just yesterday, who is doing research on dementia and Alzheimer. He identified that indeed infrared spectroscopy may be the tool to actually identify this disease way before current medical diagnostics can do so. This would be very important because now first medication is becoming available, but this is efficient only if what can use this at the earliest possible stage. He just showed yesterday in his talk that actually there is evidence that the disease starts developing at least 15 years before current technology can actually safely diagnose it. There is quite some room for improvements.

Smith: Yes. Goodness. This does bring with it profound ethical implications. I guess that part of the challenge is to have a discussion about the ethical use of such technology. Should they arise in parallel with the development of the technology, because it’s not straightforward what one should do with information that tells people, for instance, that they are due in 15 years to get dementia.

Krausz: Of course this would be completely counterproductive if there would be no therapies that can do something about it provided the unfolding disease is diagnosed early enough. But fortunately now as opposed to just a couple of years earlier, now we are in a position to be able to say that first medication is already on the markets. It is also obvious that this medication is all the more efficient, the earlier it is being applied to the disease, at the earliest stages where it can be applied. I think in all those cases where there is some sort of medication, and fortunately this actually applies to most diseases, right? Cancer does not only cause so many deaths because there are no therapies around, but much more because unfortunately just recognised far too late. When you have symptoms and with this time you go and see a doctor and the doctor has to come up with a diagnosis, you have stage four pancreatic cancer, you have another couple of months to live, right? That’s the problem. Not that there are no therapies around, but the therapies would be efficient if the disease would be recognised at a much earlier stage. There is a huge unmet medical need in terms of early detection.

Smith: Isn’t it extraordinary that you find yourself speaking about this and having this conversation, who knows where research will take one.

Krausz: Exactly. Wow. What a beautiful point that you make here. This is also something that you can’t possibly foresee, right? Even at a time when we started thinking, wow, let’s try to do something for medicine. I would’ve never thought that one day I will say, well, that’s what I want to focus on and nothing else. Because the challenge is still huge. The difference that we can make is so big that there is nothing that would compare an importance for me to this. Why don’t I focus myself fully on this and try to infect with my enthusiasm and my dedication to disclose all the people in my environment? Because alone, I can’t do anything, right? I need a strong team and I need to convince all the others in my environment that this is something that is worthy of being pursued with all possible dedication and commitment.

Smith: Thank you very much indeed. For me, it’s been an utter joy listening to your enthusiasm. It’s been a wonderful conversation. I’m very grateful to you.

Krausz: Thank you very much, and thanks for the great questions. I enjoyed it very much too.

MUSIC

Brilliant: You just heard Nobel Prize Conversations. If you’d like to learn more about Ferenc Krausz, you can go to nobelprize.org where you’ll find a wealth of information about the prizes and the people behind the discoveries.

Nobel Prize Conversations is a podcast series with Adam Smith, a co-production of Filt and Nobel Prize Outreach. The producer for this episode was Karin Svensson. The editorial team also includes Andrew Hart, Olivia Lundqvist, and me, Claire Brilliant. Music by Epidemic sound. If you want to delve deeper into the quantum world of the super small and the super fast, listen to our episode with 2022 physics laureate Anton Zeilinger. You can find previous seasons and conversations on Acast or wherever you listen to podcasts. Thanks for listening.

Nobel Prize Conversations is produced in cooperation with Fundación Ramón Areces.

Did you find any typos in this text? We would appreciate your assistance in identifying any errors and to let us know. Thank you for taking the time to report the errors by sending us an e-mail.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Six prizes were awarded for achievements that have conferred the greatest benefit to humankind. The 12 laureates' work and discoveries range from proteins' structures and machine learning to fighting for a world free of nuclear weapons.

See them all presented here.