By Klaus Biedermann*

Prize-awarded methods

Among the Nobel Prizes in Physics, two scientists have been honored for their remarkable methods to record and present images: Gabriel Lippmann, awarded in 1908 “for his method of reproducing colours photographically based on the phenomenon of interference,” and Dennis Gabor, awarded in 1971, “for his invention and development of the holographic method.”

Both methods had the same goal of carrying image reproduction further in a way that was quite different from other earlier attempts made for the same purpose. To achieve this, Lippmann and Gabor chose a revolutionary approach to fundamental physics instead of following an evolutionary progress in engineering.

In 1886, when the art and technology of photography was still struggling to transfer the colors of nature to adequate tonal values in black and white, Gabriel Lippmann conceived a two-step method to record and reproduce color images directly through the wavelengths in the object and the subsequent photograph.

While Lippmann improved photography from black and white to color, Gabor’s holography extended photography from flat pictures to a three-dimensional image space. Procedures to offer to each eye of the viewer its own parallax – stereoscopy – are as historical as photography itself. But Gabor’s idea of a “hologram” was to store all the information in all image space and not just in one slightly different second photograph.

Ideas behind the methods

Interestingly, the physics behind both inventions can be understood on the same principle, namely using the wave nature of light, which involves encoding the image field by interference, recording the structure in a photographic plate, and then reading out the image field again by sending light and getting it modulated in this structure.

Wave optics and interference: a primerWhen we look at optical images, we usually think of light rays. Both Lippmann’s photography and Gabor’s holography rely on the wave propagation of light.

|

| A wave arises and propagates on water. Photo: Prof. Andrew Davidhazy, Rochester Institute of Technology |

Wave phenomena appear everywhere in physics. Most obviously, we see them on a water surface. We may observe that waves spread out with a propagation direction, a propagation velocity or speed, and a length of their period.

When two or more waves are superimposed, we notice that this results in a pattern which is known as “interference.” Such an interference structure contains information on all the fields interacting. When one field is known, information on the other fields can be also deduced.

Compared to water or sound, the wave nature of light is far more difficult to observe. The small wavelengths (e.g. 0.4 – 0.7 µm, i.e. 0.0004 – 0.0007 mm, for visible light) and worse, the frequencies of the wave vibrations are 750 to 400 THz (1 terahertz is a million times million periods a second). The frequency of light is fundamental, there is no mechanism to read out the motion of light waves. However, a wave motion can be probed by the interaction with a very similar one, the effect called interference, to the degree of a standstill in a “standing wave”.

A standing wave arises from the interference of two waves of exactly the same frequency but opposite phase of the vibration amplitude. In high-school, standing waves are demonstrated by waves oscillating along a rope that are reflected at a stop and return. For light, the stop is a mirror where the impinging wave is reflected, as illustrated in the figure to the left. At the metallic mirror, nature avoids absorption of the wave by switching the phase at the same instant as the propagation direction turns over.

|

| The reflection of a light field in a mirror generates a standing wave (left). A scheme showing how Lippmann used standing waves to encode color in a photograph (right). |

At the mirror, the resulting field is always zero; at a quarter of a wavelength away from the mirror, the sum of the two fields will periodically change at values of up to (+) and (-) 2 x the amplitude. This is what in acoustics is taught as a “node” and a “bulge” of the sound vibration, respectively. In optics, the interference will be observed as dark and bright fringes and can be recorded in photographic film or any other light detector.

For a stable pattern of interference fringes, the waves have to be of the same wavelength – the light is monochromatic – and they have to have the same phase relation, i.e. to be of the same origin – the light has coherence.

This condition is achieved when waves are split from the same source and the delay between the original and mirrored wave is only a few wavelengths apart. Standing waves in a thin oil film on wet asphalt and in the emulsion used in Lippmann’s photography fulfil this condition. However, for three-dimensional holography, Gabor had to generate the fringes by letting the object field interfere with an external reference field. A light source of an adequate degree of monochromaticity and coherence became first available through the laser.

Lippmann’s color photography

How could Gabriel Lippmann make use of interference effects to achieve color photography? The primer on wave optics and interference told us that light of different wavelengths will generate standing wave patterns at corresponding period lengths. Lippmann started out with a pattern of standing waves, where a wavefield meets itself again after it is reflected in a mirror. He projected an optical image as usual onto a photographic plate, but through its glass plate with the almost transparent emulsion of extremely fine grains on the backside. Then he added the interference effect by placing a mercury mirror in contact with the emulsion. The image went through the emulsion, hit the mirror, and then returned the light back into the emulsion. A suitable thickness of this photographic layer corresponds to around ten or more wavelengths. The image projected onto the plate did not plainly expose the emulsion according to the local distribution of irradiance. Rather, the exposure was encoded when the wave field returned within the emulsion and created standing waves, whose nodes gave little exposure, whereas the bulges gave maximum effect. Hence, after development, the photographic layer contained some twenty or more lamellae of silver grains with different periods for different colors in the image.

Gabriel Lippmann

When, after development, white light is shone on the plate in reflection, it will be scattered at these silver grains in all directions. Into the direction from which the standing wave pattern had been generated, the scattered light fields having the same wavelength as the period of the lamellae will be in phase, interfere constructively, and together create a strong color image. Certain elegant insects and butterflies have created such periodic lamellae without having been taught the optics of scattering or diffraction.

We see that in essence, this form of imaging builds on a symmetric two-step process of interference and diffraction: first by encoding the image into an interference pattern, and then reconstructing the image by diffraction at this pattern.

Gabor’s hologram

The same two-step principle holds for Gabor’s idea of wave front reconstruction.

From Lippmann, we learned how to record and retrieve color information on a flat picture in contact with a photographic plate. If Gabor wants to reconstruct wavefronts in three-dimensional space, he needs a field of view, and we imagine that he instead has to abandon wavelength range. The process has to be done in monochromatic light. The reference for interference is no longer the reflection of the image field itself (in holography usually called object field), rather it has to be provided by a separate reference field. The angle between the reference field and any point from the object field determines periodicity and orientation of the resulting, much more complicated interference structure, which he called a “hologram.” This also means that in order to obtain decent interference, the coherence length has to be larger than the path difference between any point at the object field and the reference field.

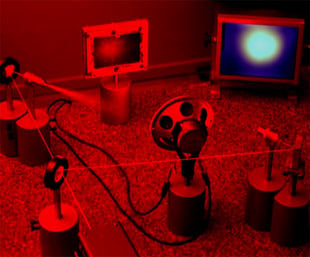

|

A setup showing how a hologram is being made. Light comes from the laser at the lower left. From the mirror and the lens at the upper left, it illuminates the object, a loudspeaker, in the center. The loudspeaker spreads its light to the photographic plate facing it. Since there is no lens at which to project an image, the irradiance from the loudspeaker to the plate is quite uniform. However, a portion of the laser beam has been split off as a reference field at the partly transparent mirror, and it now meets the object field at the photographic plate after about the same travel time. The two fields then interfere and expose together an intricate standing wave pattern in the emulsion. After development, the reference field alone shines on the plate and becomes modulated in the structure, i.e. the hologram. The light is distributed into several diffracted fields, of which one is called the reconstructed field that propagates through the plate as a replica of the object field which previously hit the plate. In this way, the hologram acts like a window with a memory. Why a hologram of a loudspeaker? The setup illustrates one of the important technical applications of holography, namely vibration analysis. By using hologram interferometry vibration mode patterns can be made visible on any surface, much like the sand on flat membranes in the Chladni figures more than two hundred years ago. |

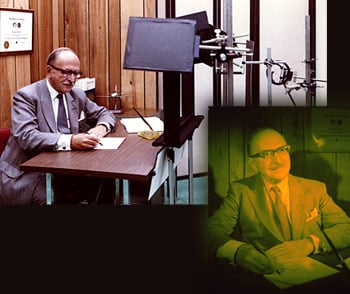

When Gabor conceived the process of wavefront reconstruction in 1948, then intended to correct aberrations in electron microscopes, the available mercury arc lamp restricted his optical feasibility experiment to an object size of a few millimeters. A breakthrough came first in 1963 when Leith and Upatnieks at the University of Michigan demonstrated three-dimensional images from holograms made by laser. A highlight of the art became the portrait hologram of Gabor made with a pulse laser in the spring of 1971; the volume of the object space is several cubic meters.

|

| A large holography setup similar to the one shown with the loudspeaker. Here we see in early 1971, Dennis Gabor at a desk explaining holography and being preserved for eternal life in 3-D (three-dimensional) through a Lippmann-type photographic plate of 50 cm x 60 cm. The plate holder is facing Gabor, just in the center of the arrangement. Setup and photo: McDonnell Douglas Electronics, MissouriInset: Image of Gabor seen through the hologram. The ample panoramic view into his office is, in an ordinary photographic shot, inevitably reduced to a modest 2-D (two-dimensional). Hologram image: Klaus Biedermann at the “Laser Grotto,” KTH, Stockholm |

Gabriel Lippmann

Gabriel Lippmann was French, born 1845 in Hollerich, Luxembourg, and died in 1921. He grew up and was educated in Paris. Among his many interests, he studied French and German literature, and received a doctorate in philosophy in Germany in 1874. In 1875, he received another doctorate, in science on the capillary electrometer, at the Sorbonne. He held university positions in Paris from 1878 to the end of his life.

One anecdote as a spin-off on Lippmann’s activities: In his laboratory, Lippmann supported a Polish student in her research, Marie Sklodowska. He also introduced her to his collaborator in piezoelectricity, Pierre Curie. The two got married in 1895, and the research output of the Curie family, including daughter Irène and son-in-law Frédéric Joliot, resulted in the end in five Nobel Prizes on radioactivity.

Through his Nobel Prize, Lippmann is best known to the general public for the process of color photography bearing his name. In science, he is famous for many developments in metrology, astronomy and seismology. One of them is the coelostat, the instrument used in telescopes to keep the images of the stars in place for arbitrarily long periods of exposures.

Another of his inventions in optics was “integral photography,” which he published in 1908. When holography in the late 1960s once more ignited great interest for three-dimensional imaging, scientists and inventors remembered Lippmann’s idea. His goal had been to produce pictures with which an observer can experience changing parallax when moving with the eyes in horizontal and vertical directions. His solution was to look at a virtual display of an almost continuous periodic pattern of small camera lenslets, each of them having recorded a photograph of the object at its direction.

Dennis Gabor

Dennis Gabor was Hungarian, born 1900 in Budapest, became an English subject, died in 1976 in London. He received his first patent at the age of eleven, obtained the diploma in electrical engineering in 1924 at the Technische Hochschule in Berlin, and Dr.-Ing. in 1927 on a thesis of a high-speed cathode ray oscilloscope. He became employed at Siemens & Halske, developing gas discharge tubes.

There was a very research-intensive environment in Berlin during these years, with hot topics including the electron microscope of pioneers Knoll and Ruska – Ernst Ruska received a Nobel Prize in Physics in 1986 – and cinematography, fields to which Gabor, many years later, would come back to make contributions.

When Hitler came to power, Gabor left Berlin and eventually took employment in England in 1934 with the British Thomson-Houston Co. He continued to develop gas discharge tubes. After the war, he also worked on communication theory, stereoscopic cinematography, and a new idea, wavefront reconstruction, which he saw as a remedy to the problem of aberrations in the electron microscope. From 1949, Gabor joined the Imperial College of Science and Technology in London, where he became a professor of Applied Electron Physics.

“Wavefront reconstruction” was one of the many ideas of Dennis Gabor’s, whose final success had to wait for the solution of problems, and the talent and accomplishments of other researchers.

Parallels in life

Lippmann and Gabor had similar intellectual backgrounds, and grew up and worked in a multicultural environment.

In their careers, they did not work on one great life-time question but on many different projects, of which several were very successful. In addition to fundamental work in science, important parts of their efforts included inventing and systems engineering. Both obtained many patents.

The implementation of their ideas required new solutions, notably recording materials and light sources: In years of hard work Lippmann elaborated his own photographic process, “Lippmann plates” of extremely high resolution, still being manufactured today. In addition, color photography, of course, needed panchromatic plates; to extend sensitization over the whole visible spectrum, Lippmann teamed up with the Lumière brothers, at that time the leading photographic manufacturers in Europe. For Gabor’s invention, wavefront recording needed radiation of such a high degree of coherence which is not available in nature. Luckily for the next generation of researchers, the principle of the laser offered such a light, and holography suddenly boomed. For the other prerequisite, namely photographic plates of extremely high resolution, Lippmann had already procured them before 1900.

Many researchers will certainly, with understanding, read Lippmann’s sigh at the end of his Nobel Lecture: “Life is short and progress is slow.”

What came out in the long run?

Lippmann photography could not evade the handicap of high-resolution plates requiring exposure times from minutes to hours. However, Lippmann’s demonstration and the feasibility of taking photographs in natural colors stimulated the desire for such technologies. The Lumière brothers developed, in parallel with the work they did for Lippmann, a process of their own, based on transparent filters in three colors (in structure similar to today’s TV screens). Their “Autochrome” method prevailed into the 1930s, becoming replaced by the present color photography technology, which generates the dye stuff in three film layers during development. However, Lippmann photography is still held in high regard in science and teaching; there is no other way to image spectra correctly.

In 1962, the Russian Y.N. Denisyuk realized the relationship of the principles in Lippmann’s and Gabor’s imaging methods. He suggested a combination of using Lippmann plates for making three-dimensional images in reflection. With the emergence of laser holography, Denisyuk’s invention became practical as “white-light reflection holograms” or “Lippmann holograms.”

Gabor’s wavefront reconstruction scheme was a new principle in optics. However, the application to electron microscope lenses was not realized, and the idea was confined in advanced textbooks on optics. The situation changed in an unexpected way when Leith and Uptanieks in 1963, showed sensational, really three-dimensional pictures made possible by laser hologram recording. Great expectations were stirred up for all kinds of pictures becoming three-dimensional through holograms. The technology culminated in the holographic portrait taken of Dennis Gabor in early 1971. However, three-dimensional pictures did not generate commercial volume. Instead, there followed another unexpected application: with a hologram, wavefronts of any kind can be compared by interference, not just lenses and mirrors. Since the end of the 1970s, hologram interferometry is a standard measurement technology for deformation and vibration analysis (see figure on hologram set-up), today further facilitated through on-line digital image capture and fast computers. Interestingly, lasers and computers brought back holograms close to Gabor’s original application, providing general optical elements, holographic gratings, holographic X-ray lenses, hybrid diffractive optics, optical pattern recognition, and more. Holograms generated by computer can calibrate odd optical or mechanical surfaces to a wavefront just mathematically postulated, or produce exotic optical components for, e.g. CD players, focusing screens or autofocus devices for cameras. Today, there is real commercial volume in holograms laminated on any credit card, ID-document, banknote, and for brand merchandise verification. These holograms are embossed surface reliefs, but also stacks in depth as Lippmann holograms. At present, researchers dream of small crystal cubes as holograms for data memories with extremely high capacity and parallel throughput. Apart from all the new applications, Gabor’s holography has done a great service to understanding optics; almost any student in high school will have made a hologram as a lab exercise.

References

G. Lippmann, “La photographie des couleurs,” Comptes Rendues des Scéances de l’Académie des Sciences, Paris, 112, pp. 274-275, 1891.

G. Lippmann, “Sur la théorie de la photographie des couleurs simples et composées par la méthode intérférentielle,” J. de Physique 3, 97-107, 1894.

D. Girardin, Musée de l’Elysée Lausanne, 2000

(All of Lippmann’s color photographs and a large collection of Lippmann plates by other photographers are conserved in this museum).

D. Gabor, “A new microscopic principle,” Nature 161, pp. 777-778, 1948.

E.N. Leith and J. Upatnieks, “Photography by Laser,” Scientific American 212, pp. 24-35, 1965.

* Klaus Biedermann is professor emeritus in physics at KTH (Kungliga Tekniska Högskolan), the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm. He was born in 1935 in Munich, Germany, and first learned about Lippmann photography from his father, a physicist. Did his diploma thesis in nuclear physics at the Technical University of Munich and received his Ph.D. on optical transfer theory at the Department of Photographic Science with Hellmut Frieser, who had started research at Siemens in 1930 as Gabor did; together with Hellmut Frieser met Gabor in 1964. Did a postdoc project in 1966 at KTH on the role of the photographic process for holography. Arranged for Gabor’s Nobel lecture 1971 the display of Gabor’s holographic portrait, and a copy of it later at the lab’s “Laser Grotto,” the very early and still active science center at KTH. Biedermann was acting professor in 1972, full professor in 1978, and was responsible for the independent Institute of Optical Research, offering R&D and service to industry. Optics happened to have its most fruitful quarter century then. With competent colleagues and ambitious students, the two laboratories reaped research achievements, most PhD exams at KTH, new technology in old industries and start-up companies, and young optics researchers and professors in industry and academe in Sweden and abroad.

First published 15 May 2005