by Geir Lundestad*

Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, 1990 –

Long history

There are over one hundred peace prizes in the world. The exact number depends on how one chooses to define the term “peace”. None of the other peace prizes are as well known as the Nobel Peace Prize.

Time and again, as Secretary to the Norwegian Nobel Committee, I am asked the same question by representatives of the other awards: why does “everyone” know about the Nobel Peace Prize, while so few know about their prize? Or, to put it differently: why does the world take such an interest in what a committee of five internationally relatively unknown Norwegians may decide about who has done most for peace?

I think there are three or four reasons why the Nobel Peace Prize enjoys such prestige. For one thing, the Norwegian Nobel Committee, known until 1977 as the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Parliament (Storting), has been engaged in this task ever since 1901.

In that year the Peace Prize, like the other Nobel Prizes, was awarded for the first time. It was shared between Henri Dunant, the founder of the Red Cross, and Frédéric Passy, the leading international pacifist. Even that first award was controversial, with criticism going in two directions. Passy’s supporters were critical of Dunant. Admittedly the Red Cross alleviated suffering once war had broken out, but what did the organization actually do to prevent war? Those who favoured Dunant objected to his having to share the prize with Passy. Critical questions of this kind have come from various sources through the years but, unlike nearly all the other peace prizes, the Nobel Peace Prize is firmly established, work on it having gone on continuously since 1901.

The Nobel family

The second reason is that the Peace Prize is one of a family, the Nobel family, to which I believe every member benefits from belonging. The Nobel Peace Prize may perhaps attract as much international attention and publicity as all the other Nobel Prizes put together. This is attention which I believe also our Swedish friends appreciate. Similarly, we on the Norwegian side are very conscious of the value of being associated with the prestige of the more scientific awards in Physics, Chemistry and Medicine. (The prize which has most in common with the Peace Prize is the Literature Prize. “Everybody” can and should hold views on peace and literature; one should probably not expect most people to take as keen an interest in physics, chemistry or medicine.)

A respectable record

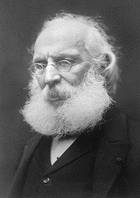

Thirdly, I believe that the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s performance has contributed to the standing of the Nobel Peace Prize. That is not to say that the Committee has an unblemished record. Certainly there have been persons who deserved a Nobel Peace Prize but were never awarded one. With hindsight, most people would probably agree that Mahatma Gandhi – the twentieth century’s leading advocate of non-violence – should have been given the Peace Prize. Perhaps Jean Monnet, too – “father” of European integration – ought to have been awarded the Peace Prize. And on the other hand, there have certainly been Laureates who should not have won the Peace Prize, but the Secretary to the Nobel Committee would probably do well to keep his personal favourites on that list to himself.

By and large, however, the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s selections have contributed steadily to enhancing the reputation of the Peace Prize. Some names of course stand out more than others: Woodrow Wilson (1919), Fridtjof Nansen (1922), Carl von Ossietzky (1935), Albert Schweitzer (1952), Dag Hammarskjõld (1961), Martin Luther King, Jr. (1964), Andrei Sakharov (1975), Mother Teresa (1979), Mikhail Gorbachev (1990), and Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk (1993). Nansen is one of two Norwegians to receive the Prize. The other is Christian Lange (1921). That the Committee is from a small country and has so rarely rewarded its own countrymen has probably also contributed to the high international status of the Prize.

It can of course also be argued that the value in money of the Peace Prize, like the other Nobel Prizes, adds to its prestige. That may be so, but it should also be noted that it was only in its very earliest and very latest years that the value of the Prize was exceptionally high. There are in fact even today other peace prizes that are more valuable – in terms of money.

|

| Why was Mahatma Gandhi, the twentieth century’s leading advocate of non-violence, never awarded the Nobel Peace Prize? Photo: Archives of the A/S Kunnskapsforlaget, Oslo |

The significance of the Peace Prize

So the world cares about the Peace Prize. That leads on to the question of whether the Peace Prize has any effect on what happens in the world.

If the purpose of the Nobel Peace Prize had been to establish peace all over the world, it would clearly have failed. We see at all too frequent intervals how limited the powers are even of the American President, the most powerful man in the world. With that in mind, we can hardly expect the Nobel Peace Prize to play a decisive part in international politics.

A determining impact on matters of war and peace would be far too strict a criterion for the importance of the Peace Prize. Even a limited influence on international politics should be celebrated as a victory for a prize that is awarded only once a year. And I do believe that the Peace Prize does have an influence.

The Peace Prize to Aung San Suu Kyi in 1991 is a good example of what the Prize can contribute and of its limitations. I was able to watch that process particularly closely, and there can be little doubt that the award in 1991 helped to move Burma higher on the international agenda. The United Nations, till then unable to adopt a resolution condemning Burma’s military regime, proceeded to do just that. Several countries, the United States, major EU countries, even Japan, began placing greater emphasis on human rights in their policies towards Burma. These are the remarkable developments, not the fact that the Peace Prize did not lead to the fall of the military government or even to Aung San Suu Kyi’s release from house arrest.

Many similar effects can be seen to have resulted from the award of the Peace Prize in 1996 to Bishop Carlos Belo and José Ramos-Horta for their struggle for East Timor’s right of self-determination. Indonesia’s invasion of East Timor in 1975 resulted in the loss of perhaps as many as 200,000 lives, of a population of some 700-800,000. This was one of the major tragedies of recent decades, yet it was gradually being forgotten. Here, too, however, the Peace Prize led to closer involvement in the conflict on the part of the United Nations, and to the modification by the United States and several EU countries of their support for the Indonesian authorities, especially behind the scenes.

In 1997-98 Indonesia’s economy collapsed. This led to sweeping political changes and in 1999 it seemed that East Timor might gain far-reaching autonomy, even independence. In the slightly longer term, I think there is reason to be relatively optimistic with regard to developments also in Burma. And many are the Peace Prize Laureates who have reported how previously closed doors were suddenly opened to them after they had received the Prize. That effect is of course greatest for the less well-known Laureates.

The annual Nobel Peace Prize awards are major media events. Nobel Peace Prize Laureate José Ramos-Horta, Committee Chairman Francis Sejersted and Nobel Institute Director Geir Lundestad meeting the press during Horta’s arrival in Oslo in 1996.

Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute

Photo: Arne Knudsen

A controversial prize

Some will presumably feel that there is something wrong with a prize which so often proves controversial. A more correct view to take might be that the Peace Prize has its present position partly because the Norwegian Nobel Committee has had the courage to take controversial decisions. Awards to a few of the greatest and most important names in the history of the Peace Prize, like Albert Schweitzer and Mother Teresa, have probably won fairly general applause, but it is the relatively controversial names that more often stand out: Carl von Ossietzky, a selection which made Hitler so furious that he prohibited Germans from receiving any Nobel Prize; Martin Luther King, Jr., who shocked many white Americans; Andrei Sakharov, who outraged the Soviet leaders; and Mikhail Gorbachev, who aroused the fury of many Russians and Balts.

So one should not depart from right decisions, even though they are controversial. On the other hand, being controversial can hardly be an end in itself. On three occasions, awards were so hotly disputed that members withdrew from the Norwegian Nobel Committee: to Ossietzky (when two members withdrew, in part to maintain a clear distinction between Norwegian officialdom and the Nobel Committee); to Kissinger and Le Duc Tho (1973), when Tho refused the prize – the only person ever to have done so – and the other winner, Kissinger, did not come to receive the Prize in person and two members of the Committee withdrew; and to Arafat, Peres and Rabin (1994), when one Committee member withdrew. Two of these awards are fairly generally considered successes, whereas many are more critical of the most controversial award of all, the one made in 1973 to Kissinger and Le Duc Tho.

Some lines of development

Some may think a Nobel Peace Prize rather strange which can be awarded both to a Mother Teresa and to a Yasser Arafat, to cite two Laureates whom many may see as opposite extremes. The simplest answer to such criticism is that this can only be a problem to those who can only see one path to peace. Most of us presumably believe that there are many different routes to peace, in which case every different category of prize-winner can have a contribution to make.

Certain distinct lines of development can be pointed out in the history of the Peace Prize. Until 1960, with only one exception, Foreign Minister Lamas of Argentina (1936), the Peace Prize went exclusively to Europeans and North Americans. Since 1960, it has gradually developed into the global prize which it is today, with several Laureates from every continent. An increasing number of women have also been awarded the Peace Prize. Admittedly the first one was relatively early, although too late in the opinion of her adherents: she was Bertha von Suttner (1905), an author whose message was peace and a friend of Nobel’s who urged him to include a Peace Prize among the Nobel Prizes. But after that progress was slower. With three female Laureates in the 1990s, Aung San Suu Kyi, Rigoberta Menchú, and Jody Williams, the total has now reached ten.

The future is always difficult to forecast. But I feel quite confident that the Nobel Peace Prize will continue to approach the same problem areas in the 21st century as it tackled in its first hundred years. The connections between the environment and peace look like offering the next area into which the concept of peace will be extended. And no doubt the Prize will continue to be controversial. That is how it will attract attention and thereby secure the best support for the work of the many different Laureates who will win the Peace Prizes of the future.

|

| Jody Williams, coordinator of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines, was the tenth woman to become a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate in 1997. Copyright © The Norwegian Nobel Institute Photo: Arne Knudsen |

* Geir Lundestad has been Director of the Norwegian Nobel Institute in Oslo and Secretary of the Norwegian Nobel Committee since 1990. He was born in Sulitjelma, a mining community in Northern Norway, in 1945. He received his MA (Cand. philol.) in history from the University of Oslo in 1970, PhD from the University of Tromsø in 1976.

Lundestad held positions at the University of Tromsø from 1974: Associate Professor of History, Professor of American Civilization 1979-88, Professor of History 1988-90. He has also been a research fellow at Harvard University (1978-79, 1983) and at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington, D.C. (1988-89). While being the Director of the Nobel Institute, Lundestad is also Adjunct Professor of International History at the University of Oslo.

His main publications are: The American Non-Policy Towards Eastern Europe 1943-1947 (1975), America, Scandinavia and the Cold War 1945-1949 (1980), East, West, North, South. Major Developments in International Politics since 1945. (First Norwegian Edition in 1985, later revised, Fourth Edition 1999), “Empire” by integration: the United States and European integration 1945-1997 (1998).

First published 3 December 1999