Toni Morrison – Bibliography

| Novels |

| The Bluest Eye. – New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970 |

| Sula. – New York: Knopf, 1973 |

| Song of Solomon. – New York: Knopf, 1977 |

| Tar Baby. – New York: Knopf, 1981 |

| Beloved. – New York: Knopf, 1987 |

| Jazz. – New York: Knopf, 1992 |

| Paradise. – New York: Knopf, 1998 |

| Love. – New York: Knopf, 2003 |

| A Mercy. – New York : Knopf, 2008 |

| Home. – New York : Knopf, 2012 |

| Miscellaneous |

| Dreaming Emmet (performed 1986, but unpublished) |

| Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination. – Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press 1992 |

| Remember: The Journey to School Integration. – Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2004 |

| What Moves in the Margin : Selected Nonfiction / edited and with an introduction by Carolyn C. Denard. – Jackson : Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2008 |

| For children, with son Slade Morrison |

| The Big Box. – New York: Hyperion/Jump at the Sun, 1999 |

| The Book of Mean People. – New York: Hyperion, 2002 |

| The Lion or the Mouse?. – New York: Scribner, 2003 |

| The Ant or the Grasshopper?. – New York: Scribner, 2003 |

| The Poppy or the Snake?. – New York: Scribner, 2004 |

| Peeny Butter Fudge. – New York : Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2009 |

| The Tortoise or the Hare. – New York : Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2010 |

| Little Cloud and Lady Wind. – New York : Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2010 |

| Please, Louise. – New York : Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2013 |

| Reference works (selected) |

| Rice, Herbert William, Toni Morrison and the American Tradition: a Rhetorical Reading. – New York: Lang, 1998 |

| Mori, Aoi, Toni Morrison and Womanist Discourse. – New York: Lang, 1999 |

| Duvall, John Noel, The Identifying Fictions of Toni Morrison: Modernist Authenticity and Postmodern Blackness. – Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001 |

| The Toni Morrison Encyclopedia. Edited by Elizabeth Ann Beaulieu. – Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 2003 |

| Toni Morrison and The Bible : Contested Intertextualities / edited by Shirley A. Stave. – New York : Peter Lang, 2006 |

The Swedish Academy, 2013

Toni Morrison – Banquet speech

Toni Morrison delivering her speech.

© Nobel Foundation. Photo: Boo Jonsson

Toni Morrison’s speech at the Nobel Banquet, December 10, 1993

Your Majesties, Your Royal Highnesses, Ladies and Gentlemen,

I entered this hall pleasantly haunted by those who have entered it before me. That company of Laureates is both daunting and welcoming, for among its lists are names of persons whose work has made whole worlds available to me. The sweep and specificity of their art have sometimes broken my heart with the courage and clarity of its vision. The astonishing brilliance with which they practiced their craft has challenged and nurtured my own. My debt to them rivals the profound one I owe to the Swedish Academy for having selected me to join that distinguished alumnae.

Early in October an artist friend left a message which I kept on the answering service for weeks and played back every once in a while just to hear the trembling pleasure in her voice and the faith in her words. “My dear sister,” she said, “the prize that is yours is also ours and could not have been placed in better hands.” The spirit of her message with its earned optimism and sublime trust marks this day for me.

I will leave this hall, however, with a new and much more delightful haunting than the one I felt upon entering: that is the company of Laureates yet to come. Those who, even as I speak, are mining, sifting and polishing languages for illuminations none of us has dreamed of. But whether or not any one of them secures a place in this pantheon, the gathering of these writers is unmistakable and mounting. Their voices bespeak civilizations gone and yet to be; the precipice from which their imaginations gaze will rivet us; they do not blink nor turn away.

It is, therefore, mindful of the gifts of my predecessors, the blessing of my sisters, in joyful anticipation of writers to come that I accept the honour the Swedish Academy has done me, and ask you to share what is for me a moment of grace.

Toni Morrison – Photo gallery

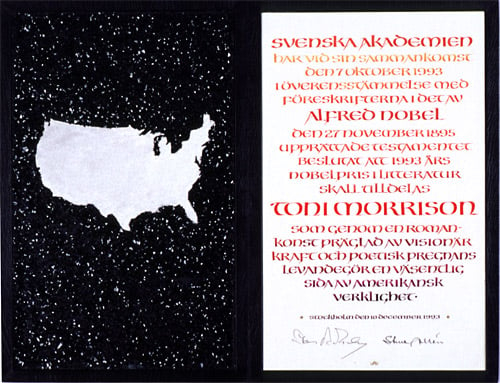

Toni Morrison – Nobel diploma

Copyright © The Nobel Foundation 1993

Artist: Bo Larsson

Calligrapher: Annika Rücker

Toni Morrison – Other resources

Links to other sites

On Toni Morrison from Pegasos Author’s Calendar

Toni Morrison – Nobel Lecture

Nobel Lecture December 7, 1993

Listen to an audio recording of Toni Morrison’s Nobel Lecture

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind but wise.” Or was it an old man? A guru, perhaps. Or a griot soothing restless children. I have heard this story, or one exactly like it, in the lore of several cultures.

“Once upon a time there was an old woman. Blind. Wise.”

In the version I know the woman is the daughter of slaves, black, American, and lives alone in a small house outside of town. Her reputation for wisdom is without peer and without question. Among her people she is both the law and its transgression. The honor she is paid and the awe in which she is held reach beyond her neighborhood to places far away; to the city where the intelligence of rural prophets is the source of much amusement.

One day the woman is visited by some young people who seem to be bent on disproving her clairvoyance and showing her up for the fraud they believe she is. Their plan is simple: they enter her house and ask the one question the answer to which rides solely on her difference from them, a difference they regard as a profound disability: her blindness. They stand before her, and one of them says, “Old woman, I hold in my hand a bird. Tell me whether it is living or dead.”

She does not answer, and the question is repeated. “Is the bird I am holding living or dead?”

Still she doesn’t answer. She is blind and cannot see her visitors, let alone what is in their hands. She does not know their color, gender or homeland. She only knows their motive.

The old woman’s silence is so long, the young people have trouble holding their laughter.

Finally she speaks and her voice is soft but stern. “I don’t know”, she says. “I don’t know whether the bird you are holding is dead or alive, but what I do know is that it is in your hands. It is in your hands.”

Her answer can be taken to mean: if it is dead, you have either found it that way or you have killed it. If it is alive, you can still kill it. Whether it is to stay alive, it is your decision. Whatever the case, it is your responsibility.

For parading their power and her helplessness, the young visitors are reprimanded, told they are responsible not only for the act of mockery but also for the small bundle of life sacrificed to achieve its aims. The blind woman shifts attention away from assertions of power to the instrument through which that power is exercised.

Speculation on what (other than its own frail body) that bird-in-the-hand might signify has always been attractive to me, but especially so now thinking, as I have been, about the work I do that has brought me to this company. So I choose to read the bird as language and the woman as a practiced writer. She is worried about how the language she dreams in, given to her at birth, is handled, put into service, even withheld from her for certain nefarious purposes. Being a writer she thinks of language partly as a system, partly as a living thing over which one has control, but mostly as agency – as an act with consequences. So the question the children put to her: “Is it living or dead?” is not unreal because she thinks of language as susceptible to death, erasure; certainly imperiled and salvageable only by an effort of the will. She believes that if the bird in the hands of her visitors is dead the custodians are responsible for the corpse. For her a dead language is not only one no longer spoken or written, it is unyielding language content to admire its own paralysis. Like statist language, censored and censoring. Ruthless in its policing duties, it has no desire or purpose other than maintaining the free range of its own narcotic narcissism, its own exclusivity and dominance. However moribund, it is not without effect for it actively thwarts the intellect, stalls conscience, suppresses human potential. Unreceptive to interrogation, it cannot form or tolerate new ideas, shape other thoughts, tell another story, fill baffling silences. Official language smitheryed to sanction ignorance and preserve privilege is a suit of armor polished to shocking glitter, a husk from which the knight departed long ago. Yet there it is: dumb, predatory, sentimental. Exciting reverence in schoolchildren, providing shelter for despots, summoning false memories of stability, harmony among the public.

She is convinced that when language dies, out of carelessness, disuse, indifference and absence of esteem, or killed by fiat, not only she herself, but all users and makers are accountable for its demise. In her country children have bitten their tongues off and use bullets instead to iterate the voice of speechlessness, of disabled and disabling language, of language adults have abandoned altogether as a device for grappling with meaning, providing guidance, or expressing love. But she knows tongue-suicide is not only the choice of children. It is common among the infantile heads of state and power merchants whose evacuated language leaves them with no access to what is left of their human instincts for they speak only to those who obey, or in order to force obedience.

The systematic looting of language can be recognized by the tendency of its users to forgo its nuanced, complex, mid-wifery properties for menace and subjugation. Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy or the commodity driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language – all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.

The old woman is keenly aware that no intellectual mercenary, nor insatiable dictator, no paid-for politician or demagogue; no counterfeit journalist would be persuaded by her thoughts. There is and will be rousing language to keep citizens armed and arming; slaughtered and slaughtering in the malls, courthouses, post offices, playgrounds, bedrooms and boulevards; stirring, memorializing language to mask the pity and waste of needless death. There will be more diplomatic language to countenance rape, torture, assassination. There is and will be more seductive, mutant language designed to throttle women, to pack their throats like paté-producing geese with their own unsayable, transgressive words; there will be more of the language of surveillance disguised as research; of politics and history calculated to render the suffering of millions mute; language glamorized to thrill the dissatisfied and bereft into assaulting their neighbors; arrogant pseudo-empirical language crafted to lock creative people into cages of inferiority and hopelessness.

Underneath the eloquence, the glamor, the scholarly associations, however stirring or seductive, the heart of such language is languishing, or perhaps not beating at all – if the bird is already dead.

She has thought about what could have been the intellectual history of any discipline if it had not insisted upon, or been forced into, the waste of time and life that rationalizations for and representations of dominance required – lethal discourses of exclusion blocking access to cognition for both the excluder and the excluded.

The conventional wisdom of the Tower of Babel story is that the collapse was a misfortune. That it was the distraction, or the weight of many languages that precipitated the tower’s failed architecture. That one monolithic language would have expedited the building and heaven would have been reached. Whose heaven, she wonders? And what kind? Perhaps the achievement of Paradise was premature, a little hasty if no one could take the time to understand other languages, other views, other narratives period. Had they, the heaven they imagined might have been found at their feet. Complicated, demanding, yes, but a view of heaven as life; not heaven as post-life.

She would not want to leave her young visitors with the impression that language should be forced to stay alive merely to be. The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers. Although its poise is sometimes in displacing experience it is not a substitute for it. It arcs toward the place where meaning may lie. When a President of the United States thought about the graveyard his country had become, and said, “The world will little note nor long remember what we say here. But it will never forget what they did here,” his simple words are exhilarating in their life-sustaining properties because they refused to encapsulate the reality of 600, 000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war. Refusing to monumentalize, disdaining the “final word”, the precise “summing up”, acknowledging their “poor power to add or detract”, his words signal deference to the uncapturability of the life it mourns. It is the deference that moves her, that recognition that language can never live up to life once and for all. Nor should it. Language can never “pin down” slavery, genocide, war. Nor should it yearn for the arrogance to be able to do so. Its force, its felicity is in its reach toward the ineffable.

Be it grand or slender, burrowing, blasting, or refusing to sanctify; whether it laughs out loud or is a cry without an alphabet, the choice word, the chosen silence, unmolested language surges toward knowledge, not its destruction. But who does not know of literature banned because it is interrogative; discredited because it is critical; erased because alternate? And how many are outraged by the thought of a self-ravaged tongue?

Word-work is sublime, she thinks, because it is generative; it makes meaning that secures our difference, our human difference – the way in which we are like no other life.

We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That may be the measure of our lives.

“Once upon a time, …” visitors ask an old woman a question. Who are they, these children? What did they make of that encounter? What did they hear in those final words: “The bird is in your hands”? A sentence that gestures towards possibility or one that drops a latch? Perhaps what the children heard was “It’s not my problem. I am old, female, black, blind. What wisdom I have now is in knowing I cannot help you. The future of language is yours.”

They stand there. Suppose nothing was in their hands? Suppose the visit was only a ruse, a trick to get to be spoken to, taken seriously as they have not been before? A chance to interrupt, to violate the adult world, its miasma of discourse about them, for them, but never to them? Urgent questions are at stake, including the one they have asked: “Is the bird we hold living or dead?” Perhaps the question meant: “Could someone tell us what is life? What is death?” No trick at all; no silliness. A straightforward question worthy of the attention of a wise one. An old one. And if the old and wise who have lived life and faced death cannot describe either, who can?

But she does not; she keeps her secret; her good opinion of herself; her gnomic pronouncements; her art without commitment. She keeps her distance, enforces it and retreats into the singularity of isolation, in sophisticated, privileged space.

Nothing, no word follows her declaration of transfer. That silence is deep, deeper than the meaning available in the words she has spoken. It shivers, this silence, and the children, annoyed, fill it with language invented on the spot.

“Is there no speech,” they ask her, “no words you can give us that helps us break through your dossier of failures? Through the education you have just given us that is no education at all because we are paying close attention to what you have done as well as to what you have said? To the barrier you have erected between generosity and wisdom?

“We have no bird in our hands, living or dead. We have only you and our important question. Is the nothing in our hands something you could not bear to contemplate, to even guess? Don’t you remember being young when language was magic without meaning? When what you could say, could not mean? When the invisible was what imagination strove to see? When questions and demands for answers burned so brightly you trembled with fury at not knowing?

“Do we have to begin consciousness with a battle heroines and heroes like you have already fought and lost leaving us with nothing in our hands except what you have imagined is there? Your answer is artful, but its artfulness embarrasses us and ought to embarrass you. Your answer is indecent in its self-congratulation. A made-for-television script that makes no sense if there is nothing in our hands.

“Why didn’t you reach out, touch us with your soft fingers, delay the sound bite, the lesson, until you knew who we were? Did you so despise our trick, our modus operandi you could not see that we were baffled about how to get your attention? We are young. Unripe. We have heard all our short lives that we have to be responsible. What could that possibly mean in the catastrophe this world has become; where, as a poet said, “nothing needs to be exposed since it is already barefaced.” Our inheritance is an affront. You want us to have your old, blank eyes and see only cruelty and mediocrity. Do you think we are stupid enough to perjure ourselves again and again with the fiction of nationhood? How dare you talk to us of duty when we stand waist deep in the toxin of your past?

“You trivialize us and trivialize the bird that is not in our hands. Is there no context for our lives? No song, no literature, no poem full of vitamins, no history connected to experience that you can pass along to help us start strong? You are an adult. The old one, the wise one. Stop thinking about saving your face. Think of our lives and tell us your particularized world. Make up a story. Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created. We will not blame you if your reach exceeds your grasp; if love so ignites your words they go down in flames and nothing is left but their scald. Or if, with the reticence of a surgeon’s hands, your words suture only the places where blood might flow. We know you can never do it properly – once and for all. Passion is never enough; neither is skill. But try. For our sake and yours forget your name in the street; tell us what the world has been to you in the dark places and in the light. Don’t tell us what to believe, what to fear. Show us belief s wide skirt and the stitch that unravels fear’s caul. You, old woman, blessed with blindness, can speak the language that tells us what only language can: how to see without pictures. Language alone protects us from the scariness of things with no names. Language alone is meditation.

“Tell us what it is to be a woman so that we may know what it is to be a man. What moves at the margin. What it is to have no home in this place. To be set adrift from the one you knew. What it is to live at the edge of towns that cannot bear your company.

“Tell us about ships turned away from shorelines at Easter, placenta in a field. Tell us about a wagonload of slaves, how they sang so softly their breath was indistinguishable from the falling snow. How they knew from the hunch of the nearest shoulder that the next stop would be their last. How, with hands prayered in their sex, they thought of heat, then sun. Lifting their faces as though it was there for the taking. Turning as though there for the taking. They stop at an inn. The driver and his mate go in with the lamp leaving them humming in the dark. The horse’s void steams into the snow beneath its hooves and its hiss and melt are the envy of the freezing slaves.

“The inn door opens: a girl and a boy step away from its light. They climb into the wagon bed. The boy will have a gun in three years, but now he carries a lamp and a jug of warm cider. They pass it from mouth to mouth. The girl offers bread, pieces of meat and something more: a glance into the eyes of the one she serves. One helping for each man, two for each woman. And a look. They look back. The next stop will be their last. But not this one. This one is warmed.”

It’s quiet again when the children finish speaking, until the woman breaks into the silence.

“Finally”, she says, “I trust you now. I trust you with the bird that is not in your hands because you have truly caught it. Look. How lovely it is, this thing we have done – together.”

* Disclaimer

Every effort has been made by the publisher to credit organizations and individuals with regard to the supply of audio files. Please notify the publishers regarding corrections.

Toni Morrison – Prose

Excerpt from Sula

T hen summer came. A summer limp with the weight of blossomed things. Heavy sunflowers weeping over fences; iris curling and browning at the edges far away from their purple hearts; ears of corn letting their auburn hair wind down to their stalks. And the boys. The beautiful, beautiful boys who dotted the landscape like jewels, split the air with their shouts in the field, and thickened the river with their shining wet backs. Even their footsteps left a smell of smoke behind.

It was in that summer, the summer of their twelfth year, the summer of the beautiful black boys, that they became skittish, frightened and bold — all at the same time.

In that mercury mood in July, Sula and Nel wandered about the Bottom barefoot looking for mischief. They decided to go down by the river where the boys sometimes swam. Nel waited on the porch of 7 Carpenter’s Road while Sula ran into the house to go to the toilet. On the way up the stairs, she passed the kitchen where Hannah sat with two friends, Patsy and Valentine. The two women were fanning themselves and watching Hannah put down some dough, all talking casually about one thing and another, and had gotten around, when Sula passed by, to the problems of child rearing.

“They a pain.”

“Yeh. Wish I’d listened to mamma. She told me not to have ’em too soon.”

“Any time atall is too soon for me.”

“Oh, I don’t know. My Rudy minds his daddy. He just wild with me. Be glad when he growed and gone.”

Hannah smiled and said, “Shut your mouth. You love the ground he pee on.”

“Sure I do. But he still a pain. Can’t help loving your own child. No matter what they do.”

“Well, Hester grown now and I can’t say love is exactly what I feel.”

“Sure you do. You love her, like I love Sula. I just don’t like her. That’s the difference.”

“Guess so. Likin’ them is another thing.”

“Sure. They different people, you know …”

She only heard Hannah’s words, and the pronouncement sent her flying up the stairs. In bewilderment, she stood at the window fingering the curtain edge, aware of a sting in her eye. Nel’s call floated up and into the window, pulling her away from dark thoughts back into the bright, hot daylight.

/- – -/

Every now and then she looked around for tangible evidence of his having ever been there. Where were the butterflies? the blueberries? the whistling reed? She could find nothing, for he had left nothing but his stunning absence. An absence so decorative, so ornate, it was difficult for her to understand how she had ever endured, without falling dead or being consumed, his magnificent presence.

The mirror by the door was not a mirror by the door, it was an altar where he stood for only a moment to put on his cap before going out. The red rocking chair was a rocking of his own hips as he sat in the kitchen. Still, there was nothing of his — his own — that she could find. It was as if she were afraid she had hallucinated him and needed proof to the contrary. His absence was everywhere, stinging everything, giving the furnishings primary colors, sharp outlines to the corners of rooms and gold light to the dust collecting on table tops. When he was there he pulled everything toward himself. Not only her eyes and all her senses but also inanimate things seemed to exist because of him, backdrops to his presence. Now that he had gone, these things, so long subdued by his presence, were glamorized in his wake.

Then one day, burrowing in a dresser drawer, she found what she had been looking for: proof that he had been there, his driver’s license. It contained just what she needed for verification — his vital statistics: Born 1901, height 5’11”, weight 152 lbs., eyes brown, hair black, color black. Oh yes, skin black. Very black. So black that only a steady careful rubbing with steel wool would remove it, and as it was removed there was the glint of gold leaf and under the gold leaf the cold alabaster and deep, deep down under the cold alabaster more black only this time the black of warm loam.

But what was this? Albert Jacks? His name was Albert Jacks? A. Jacks. She had thought it was Ajax. All those years. Even from the time she walked by the pool hall and looked away from him sitting astride a wooden chair, looked away to keep from seeing the wide space of intolerable orderliness between his legs; the openness that held no sign, no sign at all, of the animal that lurked in his trousers; looked away from the insolent nostrils and the smile that kept slipping and falling, falling, falling so she wanted to reach out with her hand to catch it before it fell to the pavement and was sullied by the cigarette butts and bottle caps and spittle at his feet and the feet of other men who sat or stood around outside the pool hall, calling, singing out to her and Nel and grown women too with lyrics like pig meat and brown sugar and jailbait and O Lord, what have I done to deserve the wrath, and Take me, Jesus, I have seen the promised land, and Do, Lord, remember me in voices mellowed by hopeless passion into gentleness. Even then, when she and Nel were trying hard not to dream of him and not to think of him when they touched the softness in their underwear or undid their braids as soon as they left home to let the hair bump and wave around their ears, or wrapped the cotton binding around their chests so the nipples would not break through their blouses and give him cause to smile his slipping, falling smile, which brought the blood rushing to their skin. And even later, when for the first time in her life she had lain in bed with a man and said his name involuntarily or said it truly meaning him, the name she was screaming and saying was not his at all.

Sula stood with a worn slip of paper in her fingers and said aloud to no one, “I didn’t even know his name. And if I didn’t know his name, then there is nothing I did know and I have known nothing ever at all since the one thing I wanted was to know his name so how could he help but leave me since he was making love to a woman who didn’t even know his name.

“When I was a little girl the heads of my paper dolls came off, and it was a long time before I discovered that my own head would not fall off if I bent my neck. I used to walk around holding it very stiff because I thought a strong wind or a heavy push would snap my neck. Nel was the one who told me the truth. But she was wrong. I did not hold my head stiff enough when I met him and so I lost it just like the dolls.

“It’s just as well he left. Soon I would have torn the flesh from his face just to see if I was right about the gold and nobody would have understood that kind of curiosity. They would have believed that I wanted to hurt him just like the little boy who fell down the steps and broke his leg and the people think I pushed him just because I looked at it.”

Holding the driver’s license she crawled into bed and fell into a sleep full of dreams of cobalt blue.

When she awoke, there was a melody in her head she could not identify or recall ever hearing before. “Perhaps I made it up,” she thought. Then it came to her — the name of the song and all its lyrics just as she had heard it many times before. She sat on the edge of the bed thinking, “There aren’t any more new songs and I have sung all the ones there are. I have sung them all. I have sung all the songs there are.” She lay down again on the bed and sang a little wandering tune made up of the words I have sung all the songs all the songs I have sung all the songs there are until, touched by her own lullaby, she grew drowsy, and in the hollow of near-sleep she tasted the acridness of gold, left the chill of alabaster and smelled the dark, sweet stench of loam.

Published by permission of International Creative Management, Inc.

Copyright © 1973 by Toni Morrison.

Toni Morrison – Facts

Toni Morrison – Biographical

Born Chloe Anthony Wofford, in 1931 in Lorain (Ohio), the second of four children in a black working-class family. Displayed an early interest in literature. Studied humanities at Howard and Cornell Universities, followed by an academic career at Texas Southern University, Howard University, Yale, and since 1989, a chair at Princeton University. She has also worked as an editor for Random House, a critic, and given numerous public lectures, specializing in African-American literature. She made her debut as a novelist in 1970, soon gaining the attention of both critics and a wider audience for her epic power, unerring ear for dialogue, and her poetically-charged and richly-expressive depictions of Black America. A member since 1981 of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, she has been awarded a number of literary distinctions, among them the Pulitzer Prize in 1988.

This autobiography/biography was written at the time of the award and first published in the book series Les Prix Nobel. It was later edited and republished in Nobel Lectures. To cite this document, always state the source as shown above.

Toni Morrison died on 5 August 2019.

Magical realism

Five spellbinding works by Nobel Prize laureates

“It always amuses me that the biggest praise for my work comes for the imagination, while the truth is that there’s not a single line in all my work that does not have a basis in reality,” said literature laureate and master of magical realism, Gabriel García Márquez.

His works epitomise magical realism, a genre in which the framework narrative is set in the real world, but supernatural and dreamlike elements are part of the portrayal. Like fairy tales, magical realism novels blur the lines between fantasy and reality and while they vary enormously, they tend to contain a set of similar elements.

Magical realism novels are usually set in a realistic environment. Even if the place, like García Márquez’s village of Macondo is fictitious, they contain features familiar to our everyday lives. However, these novels also include unexplained magical, supernatural or dreamlike elements, such as ghosts or the ability to fly, presented as ordinary occurrences that are freely accepted by characters.

Novels in this genre often tell the stories of people on the fringes of society. Their authors use magical realism to critique society, politics or wealth, for example, shining a supernatural light on impoverished communities or the horrors of slavery.

Authors such as Franz Kafka, whose novel The Metamorphosis bears the hallmarks of magical realism texts, wrote books before the genre was recognised. However, magical realism is most commonly associated with a group of Latin American authors including García Márquez, who penned works around 60 years ago and marked a boon in popularity for the genre.

Their version of magical realism and a clear definition of the genre evaporates when borders are crossed and blurred, and myths, beliefs and different realities mingle. Writers from all over the world have produced incredible books that have enriched the genre.

Here are five novels by Nobel Prize laureates, which most critics believe showcase magical realism. Whether the books fit neatly within the genre’s varied bookcase or not, it is generally agreed that they are truly magical works of literature.

One Hundred Years of Solitude

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1982 was awarded to one of the masters of magical realism, Gabriel García Márquez “for his novels and short stories, in which the fantastic and the realistic are combined in a richly composed world of imagination, reflecting a continent’s life and conflicts.”

García Márquez’s 1967 novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude, weaves together the magical and the mundane in Macondo, a solitary city of mirrors that reflects the world around it. Macondo is home to multiple generations of the Buendía family who encounter magic carpets and are haunted by ghosts as they navigate periodic misfortunes, some of which are fantastic such as the birth of a child with a pig’s tail, while others are more rooted in reality, such as the effects of a rigged election.

Explaining the presence of such fantastical features in this novel and other stories, García Márquez said that in Mexico, “surrealism runs through the streets. Surrealism comes from the reality of Latin America,” yet unlike surrealist poets and painters, his work is based on anecdotes, rather than being symbolic. His writing makes the impossible not only possible but strangely normal in the city of mirrors of his own invention. The microcosmos of Macondo reflects a continent and its human riches and poverty, with García Márquez strongly committed, politically, on the side of the poor and the weak against domestic oppression and foreign economic exploitation.

Blindness

Literature laureate Jose Saramago uses allegories and fanciful elements to critique society. In his novel Blindness, the population is stricken with an epidemic of blindness that quickly leads to societal collapse.

A characteristic of Saramago’s style is the blending of dialogue and narration, with sparse punctuation and long sentences that can extend for several pages. He sometimes transforms ordinary people, like his grandparents, into literary characters. He said in his Nobel Prize lecture, “this was, probably, my way of not forgetting them, drawing and redrawing their faces with the pencil that ever changes memory, colouring and illuminating the monotony of a dull and horizonless daily routine as if creating, over the unstable map of memory, the supernatural unreality of the country where one has decided to spend one’s life.”

Saramago received the Nobel Prize in Literature 1998 for his “parables sustained by imagination, compassion and irony” that the committee said enable readers to “apprehend an elusory reality,” and used his Nobel Prize lecture to talk about the power of characters.

The Books of Jacob

“I write fiction, but it is never pure fabrication. When I write, I have to feel everything inside myself,” said Olga Tokarczuk, who was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature. Known for the mythical tone of her writing and interweaving stories across time to create universal and epic stories, Tokarczuk believes “the world is made of words.” She constructs her novels in a tension between cultural opposites: nature versus culture, reason versus madness, male versus female, home versus alienation, which enables her novels to arguably be considered part of the magical realism genre.

Her historical novel Ksiegi Jakubowe (The Books of Jacob), is set in 1752 in the Podolian borderlands of what was southwest Poland where a family is gathering for a wedding. While criss-crossing Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire over 40 years, the novel portrays the 18th-century mystic and sect leader Jacob Frank whose charisma is superhuman. The character can read minds and bend nature to his will, while his prophetess cousin, Hayah can cast powerful spells to cheat death. Supernatural details aside, the work gives readers a remarkably rich panorama of an almost neglected chapter in European history.

In her Nobel Prize lecture, Tokarczuk spoke about the importance of narration and the author. “How we think about the world and – perhaps even more importantly – how we narrate it have a massive significance. […] A thing that happens and is not told ceases to exist and perishes. This is a fact well known to not only historians, but also (and perhaps above all) to every stripe of politician and tyrant. He who has and weaves the story is in charge.”

Life and Death are Wearing Me Out

Just as Tokarczuk draws upon the hidden history of her home country, Nobel Prize laureate Mo Yan’s writing often uses older Chinese literature and popular oral traditions as a starting point, combining these with contemporary social issues and his childhood memories. His narrative style bears the hallmarks of magical realism, which has had made his own to create “hallucinatory realism” which merges history and the contemporary.

Tormented by insomnia, he wrote Shengsi pilao (Life and Death are Wearing Me Out) in just 43 days. Drawing upon the Buddhist concept of the “wheel of life” to throw light on half a century of enormous changes in Chinese society and a series of tragedies associated with the land, the novel is narrated from the perspective of animals.

Despite the social criticism contained in his books, in China Yan is viewed as one of the country’s foremost authors. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature 2012.

Beloved

Toni Morrison is another author whose works including Beloved bear hallmarks of magical realism, although Morrisson herself initially disliked her novels being included in the genre. She explained that her use of enchantment comes from her own experience and that of the black people she knew. “It formed a kind of cosmology that was perceptive as well as enchanting, and so it seemed impossible for me to write about black people and eliminate that simply because it was “unbelievable”, she said.

Set in the period following the American Civil War with its commonplace mysticism and dream-like imagery, Beloved tells the story of a formerly enslaved woman, whose home is haunted by a spiteful spirit thought to be the ghost of her eldest daughter. The novel explores slavery and other themes, weaving together places and times in the network of motifs. The combination of realistic notation and folklore paradoxically intensifies the credibility of the story. There is enormous power in the depiction of the protagonist Sethe’s action to liberate her child from threat of enslavement, and the consequences of this action for Sethe’s own life.

The Nobel Prize in Literature 1993 was awarded to Toni Morrison “who in novels characterised by visionary force and poetic import, gives life to an essential aspect of American reality.”

How many of these books have you read? Which is the most magical to you?

First published 11 July 2024