A reoccurring aim among the Nobel Prize laureates’ achievements is to help us live more sustainable lives – whether it’s growing enough food to ensure nobody goes hungry, or making our chemical processes cleaner and greener. Here are some of the ways Nobel Prize laureates have worked to make the world more sustainable.

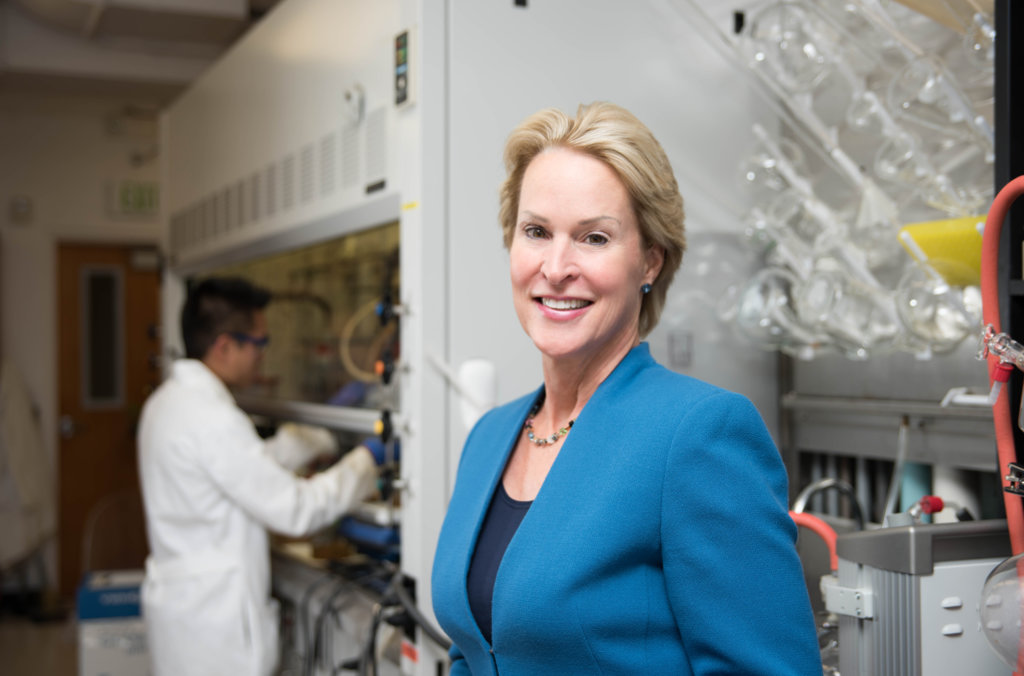

Frances Arnold

Chemistry laureate Frances Arnold has always had an interest in the environment: “I started my career back in the 1970s working in solar energy when the US had a national goal of 20% renewable energy by the year 2000,” she says. When that goal fell by the wayside Arnold changed career path, but kept her passion for sustainability. “I went into biotech at the beginning of DNA revolution. I stayed with renewable energy though, looking at ways we could replace pumping oil out of the ground.”

In 2018 Arnold was awarded the Nobel Prize for using the process of evolution to make new and better enzymes. As proteins that can make chemical reactions run faster and more efficiently, Arnold’s enzymes have the potential to clean up so-called dirty processes. Their uses include more environmentally friendly manufacturing of chemical substances, such as pharmaceuticals, and the production of renewable fuels.

“These applications are thrilling to me because I see a sustainable future for the planet by using some of these designed processes and designed molecules that nature invented,” says Arnold.

Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai was a woman of many firsts – the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize; the first female scholar from East and Central Africa to take a doctorate; the first female professor ever in her home country of Kenya.

She was also one of the Earth’s staunchest defenders.

In 1977 Maathai began encouraging women to plant trees in her home country of Kenya to combat deforestation. Her Green Belt Movement gave jobs to women and became a symbol for democratic struggle. The campaign spread, leading to the planting of trees across Africa – today over 51 million trees have been planted in Kenya alone.

Wangari felt that we could all do our bit to help the environment and ended her 2004 Nobel Prize lecture with a story calling on us to look after the earth: “I reflect on my childhood experience when I would visit a stream next to our home to fetch water for my mother. I would drink water straight from the stream … Later, I saw thousands of tadpoles: black, energetic and wriggling through the clear water against the background of the brown earth. This is the world I inherited from my parents.

Today, over 50 years later, the stream has dried up, women walk long distances for water, which is not always clean, and children will never know what they have lost. The challenge is to restore the home of the tadpoles and give back to our children a world of beauty and wonder.”

Wangari Maathai held her Nobel Lecture December 10, 2004, in the Oslo City Hall, Norway. She was presented by Professor Ole Danbolt Mjøs, Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee.

Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland

In 1974, Mario Molina and Sherwood Rowland published an article in which they demonstrated that chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases, have a damaging effect on ozone in the atmosphere. The discovery was worrying as our ozone layer is crucial for life on earth, providing protection from damaging UV radiation reaching the earth’s surface.

At the time CFCs had many uses, including propellants in spray cans and refrigerants in refrigerators. Molino and Rowland’s research led to restrictions on CFCs but it soon became clear more drastic action needed to be taken.

In 1985 scientists discovered a dramatic depletion of the ozone layer over the Antarctic – the ozone hole. Thanks in part to the pioneering work of Molina and Rowland, along with their fellow chemistry laureate, Paul Crutzen, the Montreal Protocol was introduced, which banned their use worldwide. Today the depletion of the ozone layer has slowed. It is hoped that in time it will heal completely.

Norman Borlaug

When Norman Borlaug‘s Nobel Peace Prize was announced it was declared that he “more than any other single person of this age, has helped to provide bread for a hungry world.”

A daily supply of food is essential for survival but also for peace. After the Second World War, supplying food to the world’s growing population became a hot issue. Plant geneticist Borlaug developed crops that were adapted to farming based on fertilisers and new farming equipment, resulting in higher yields.

In the 1940s and 1950s Borlaug worked in Mexico to make the country self-sufficient in grain. He recommended improved methods of cultivation, and developed a robust strain of wheat – dwarf wheat – that was adapted to Mexican conditions. By 1956 the country had become self-sufficient in wheat.

Borlaug later collaborated with scientists from other parts of the world, especially from India and Pakistan, in adapting the new wheats to new lands and in gaining acceptance for their production.

His work was central to what later became known as the ‘green revolution’, empowering nations across the world to feed themselves.

William Nordhaus

In the 1970s, after studying the emerging evidence on global warming, William Nordhaus decided he had to do something.

An economist, Nordhaus went onto to develop a model that describes how the environment and economy can affect one another. He was the first person to simulate the global interplay between the two.

Today Nordhaus’ model can be used to test the effect different policies will have on both our climate and the economy. For many years Nordhaus has advocated introducing a carbon tax, to reflect the social cost of carbon emissions.

In his Nobel Prize banquet speech Nordhaus spoke of his wish for a more sustainable future. “I hope that you can say that we, in this generation, had the resolve to overcome the obstacles and take the steps necessary to preserve our unique and beautiful planet,” he said.

Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann

Physics laureates Syukuro Manabe and Klaus Hasselmann laid the foundation of our knowledge of the Earth’s climate – and how humanity influences it.

Manabe demonstrated how increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere lead to increased temperatures at the surface of the Earth. He also led the development of physical models of the Earth’s climate.

Hasselmann created a model that links together weather and climate, answering the question of why climate models can be reliable despite weather being changeable and chaotic. His pioneering methods for identifying signals that imprint in the climate have been used to prove that the increased temperature in the atmosphere is due to human emissions of carbon dioxide.

Models have shown an accelerating greenhouse effect, a 40% increase in carbon dioxide levels since the mid-19th century and a 1°C rise in temperature over the past 150 years. Our actions will determine how dramatically Earth’s climate will change in the future, and climate models are instrumental in testing theories and solutions that could be used to mitigate its worst effects.

Benjamin List and David MacMillan

Benjamin List and David MacMillan independently developed a precise new tool for building new molecules – organocatalysis – which has made chemistry greener.

Catalysts are used to control and accelerate reactions in a vast number of industries. The laureates have shown that organic catalysts, which are cheaper and more environmentally friendly than traditional catalysts, can be used to drive multitudes of chemical reactions.

Using these reactions, researchers can now more efficiently construct anything from new pharmaceuticals to molecules that can capture light in solar cells. They have even identified an organocatalyst that can break down plastic waste.