For more than a century, Nobel Prize-awarded advances in medicine show that remarkable progress is possible. Learnings from the pandemic was a major topic at the 2024 Nobel Week Dialogue in Stockholm, alongside discussions on emerging risks and scientific breakthroughs.

Just 15 minutes – that is the amount of time it took to design the COVID-19 vaccine. After decades of work, medicine laureate Drew Weissman revealed that once they had the virus’s genetic code, the designing of the vaccine was speedy. Weissman was one of the researchers developing the mRNA vaccine that helped protect millions of people globally. However, at the 2024 Nobel Week Dialogue, he shared that his views on global health are on a cosmic scale: “I have a modern Daoist approach that starts with the universe, the solar system, the Earth, and all its elements – water, air, stone, lava – and everything that makes up Earth. Then all living things: plants and animals. When any of that is out of balance, health is disturbed.”

Weissman cited a dramatic example: 66 million years ago, a massive asteroid disrupted Earth’s balance, wiping out (non-avian) dinosaurs. The health of Earth’s biosphere took a hit which changed the course of life on Earth, paving the way for the rise of mammals and ultimately humans. Today, the environment shapes human health in profound ways, from air pollution to deadly heatwaves to the spread of disease in a globally interconnected world.

Alfred Nobel’s interest in health and medicine

Back in the 1800s, when Alfred Nobel lived, the biggest health challenge was surviving childhood. Nobel’s parents had eight children but only four made it to adulthood. Nobel complained throughout his life of ailments from indigestion, headaches, and bouts of depression. We cannot rule out that some medical problems were worsened by daily exposure to toxic chemicals. Nitroglycerin, for instance, an ingredient in dynamite, is notorious for causing severe headaches.

Thanks to advancements in science, health concerns in Nobel’s time differed greatly from today’s. Nobel followed medical science closely, jotting down ideas to cure diseases and expressing interest in emerging anaesthesia techniques. In his will, physiology or medicine was the third prize area mentioned.

The first medicine prize in 1901 honoured Emil von Behring for developing a treatment against deadly diphtheria. That same year, Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen received the physics prize for discovering X-rays, revolutionising medicine. From then on, the Nobel Prizes tell a remarkable story of medical progress.

Nobel Prize-awarded medical advancements

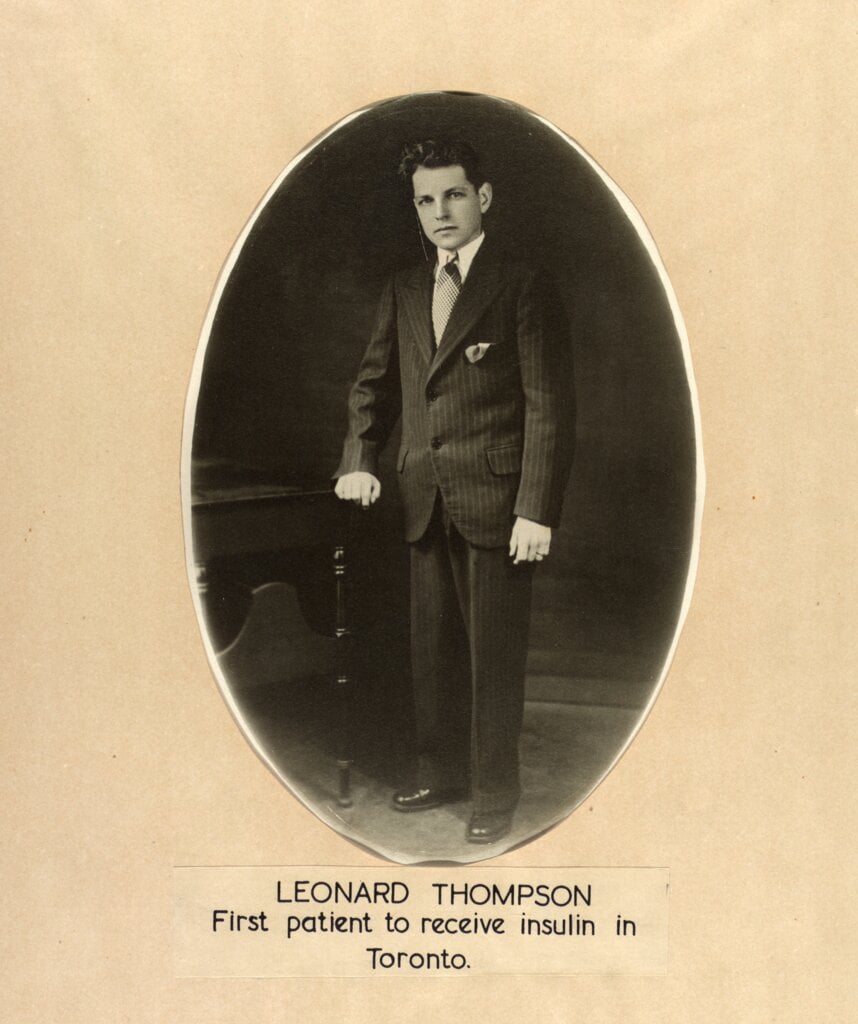

In 1922, 13-year-old Leonard Thompson became the first person to receive an insulin injection. A year later, Frederick Banting and John Macleod were awarded the Nobel Prize for this life-saving discovery. Today, millions depend on insulin to lead long, healthy lives.

Later that decade, Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin, the first antibiotic, earning the 1945 Nobel Prize. As Fleming humbly noted, “I did not invent penicillin. Nature did that. I only discovered it by accident.”

Another milestone came in the 1950s when the structure of DNA was unveiled. In 1962, Francis Crick, James Watson, and Maurice Wilkins received the Nobel Prize for this discovery, laying the foundation for modern genetics. Today, organ transplants are routine, MRI scans revolutionise diagnostics, and immunotherapy is transforming cancer treatment – all recognised by Nobel Prizes.

The future of health

Recent Nobel Prizes hint at future health innovations. CRISPR/Cas9, a precise gene-editing tool inspired by bacteria’s defence mechanisms, could revolutionise medicine. In 2020, Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their contribution to this remarkable breakthrough. By 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration, FDA, approved the first CRISPR/Cas9 therapies for sickle cell disease – a glimpse of treatments to come.

That same year, Drew Weissman, along with colleague Katalin Karikó, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to the development of the mRNA vaccine that paves the way for rapid vaccine development. Weissman’s lab now targets diseases like norovirus, Lyme disease, seasonal flu, hepatitis C, and HIV – and Weissman invests to build research capacity throughout the world so scientists can use tools he pioneered to create new vaccines.

The 2024 chemistry prize honoured pioneers unravelling protein folding – a medical grand challenge. Demis Hassabis and John Jumper were recognised for the development of AlphaFold, a tool predicting protein structures with remarkable accuracy – critical for vaccine development and drug discovery. This achievement points to the intriguing possibility that AI is poised to accelerate drug discovery and, more generally, supercharge science, ushering in faster, groundbreaking innovations.

However, the Nobel Week Dialogue also spotlighted growing challenges. When the first Nobel Prize was awarded in 1901 the global population was just 1.6 billion people. Humanity has grown to reach eight billion people today. This scale brings health risks as we transform our planet – farming at this scale changes the risk of diseases spilling over from wildlife to farm animals and to humans, for example.

During the Nobel Week Dialogue, leading climate and health academic Kristie Ebi from the University of Washington warned how disease patterns may shift – for example malaria may extend further north and south outside the tropics. On top of new risks of diseases, extreme weather will test health systems.

As Nobel Foundation chair Astrid Söderbergh Widding noted, perhaps the greatest health innovation of the past century wasn’t technological but social: the establishment of universal health norms and health as a human right. These values aren’t fully global yet. As we look to the future of health, making these values truly universal will be essential to building resilient societies.

The Nobel Week Dialogue on the future of health provided a platform to explore what health means today and how our health might improve in future. What we can learn from past Nobel Prizes is that remarkable progress is possible. In the coming decades we are likely to see many breakthroughs, which may come faster than ever before.