What does music mean to you? Do you use it to help relieve stress, anxiety and fall asleep to? For many, the value of music is endless and scientists and Nobel Prize laureates are no exception. From seeing problems in a new way to fostering discipline, expressing creativity to working as a team, music has helped many laureates in both work and life.

“Life without playing music is inconceivable for me.” – Albert Einstein

Music has often helped Nobel Prize laureates think and process scientific information in a new way. Physics laureate Albert Einstein was influenced by his mother who taught him to play the violin at a very early age. He was especially fond of Mozart, Bach and Schubert. Einstein often highlighted and emphasised the importance of music to him. In his lifetime he owned around ten violins, all receiving the nickname ‘Lina’. For Einstein, music worked as a brainstorming technique to help him reflect on his theories and resolve difficulties he encountered. He often indicated that if he hadn’t worked as a scientist, he would have become a musician. Einstein’s scientific ideas were often firstly created in the shape of images and intuitions, and later converted into mathematics, logic and words. Music helped Einstein in this thought process and helped convert the images to logic.

Physics laureate Werner Heisenberg was also highly interested in music and occasionally played together with Albert Einstein. From an early age, Heisenberg seemed destined to become a musician and concert pianist. It is said that he started reading sheet music at the age of four. However, as he grew older, his passion for science outgrew his love for music and he decided to become a scientist instead. Despite this, music remained a lifelong passion of his.

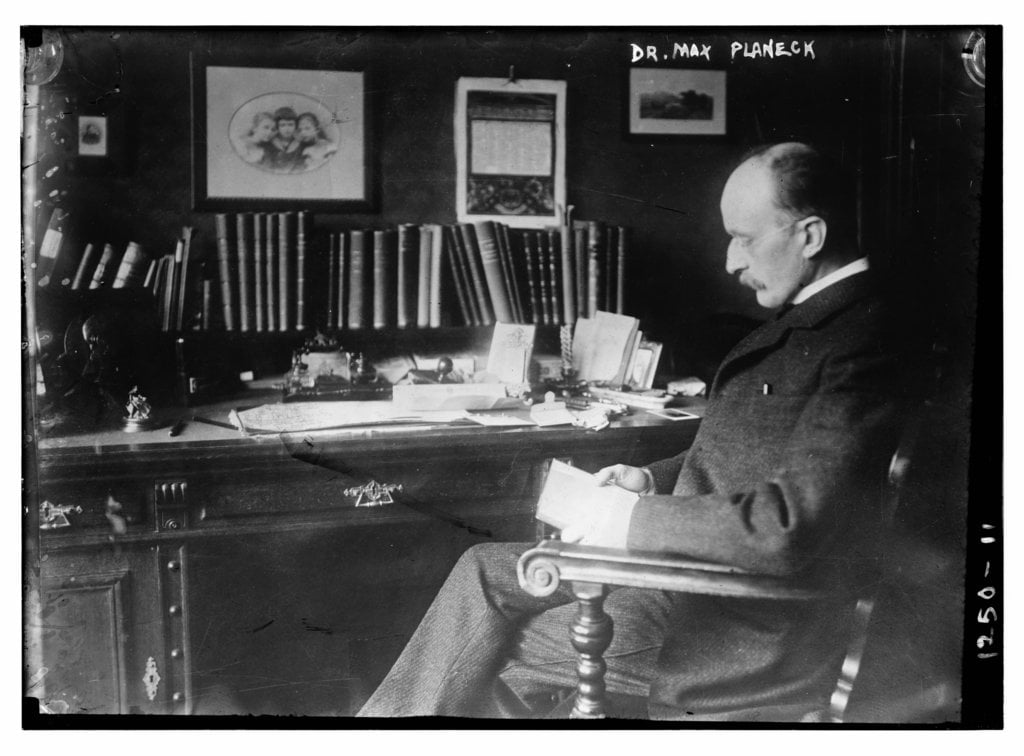

Fellow physics laureate Max Planck was similarly a very gifted physicist and musician. Planck sang as well as played the piano and organ. Einstein and Planck supposedly used to play together, finding not only a shared love for science but also music.

”I credit my musical education with my dual appreciation for discipline and hard work on the one hand, and for creativity on the other. I think trying to be marginally successful in learning how to be a musician taught me how to be a scientist: there is no creativity if one does not master the subject and pay exquisite attention to the details, but there is also no creativity if one cannot transcend the details and the common interpretation of such details, and use one’s mastery of the subject like an instrument to develop new ideas.” – Thomas Südhof in his biography

Besides helping them reflect on scientifically complex problems, music has helped Nobel Prize laureates learn discipline and the importance of a creative mind. For Thomas Südhof, awarded the 2013 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, music gave him important inputs and ideas. Similar to previously mentioned laureates, Südhof mostly enjoys classical music. Südhof played the bassoon, and says that classical music and his music teacher has had a huge influence on him. Classical music requires a creative mind as well as enormous discipline. These two factors are said to have shaped Südhof’s development as a scientist. The repetitive and disciplinary task of practicing the same symphony over and over again slowly become a part of Südhof’s personality. The repetition helped him acquire knowledge and gave him the basics to start with. However, he also realised that in order for him to use that knowledge to create something new, he needed a creative mind. Südhof sees the parallels between music and science. In science, the two requirements of practicing a lot as well as having a creative mind are necessary in order to achieve something extraordinary.

“The code of life is like Beethoven’s Symphony – it’s intricate, it’s beautiful. But we don’t know how to write like that.” – Frances Arnold in her 2018 Nobel Lecture

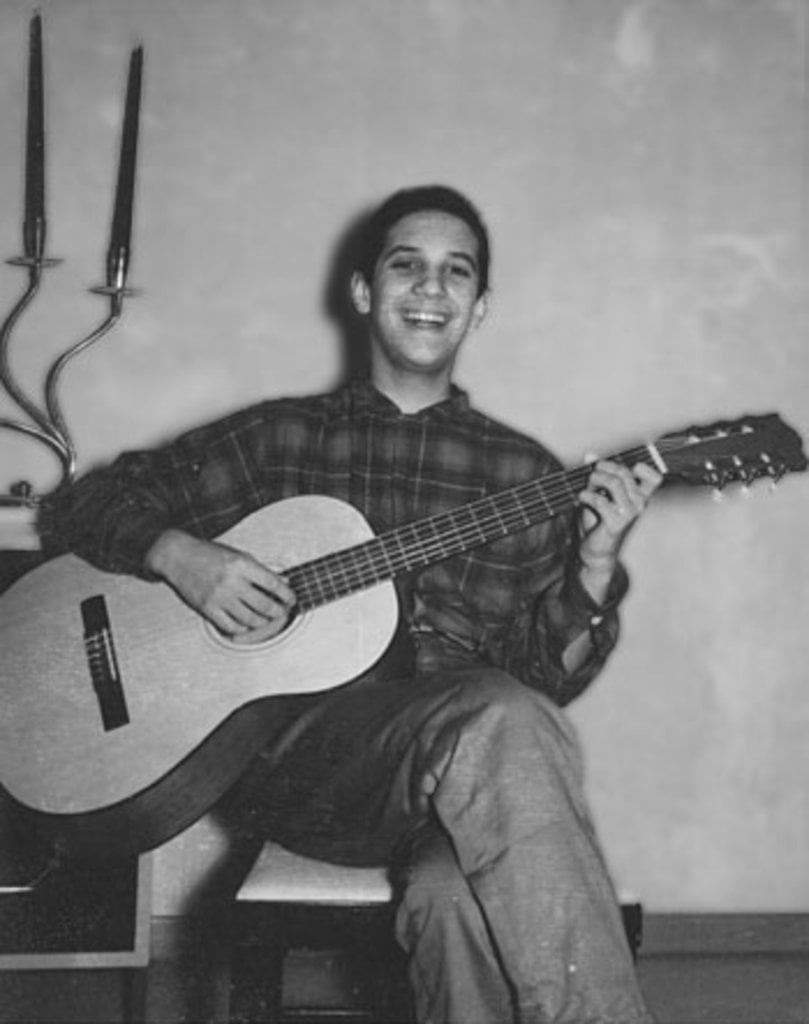

Besides music’s ability to spark creativity and teach scientists disciplinary practice, Nobel Prize laureates compare and see similarities between science and music. In her Nobel Lecture, chemistry laureate Frances Arnold mentioned the similarity between Beethoven’s symphony and her work with the code of life. They both are beautiful and intricate, however it seems as if we still need to practice if we want to write the code of life as beautiful and intricate as Beethoven wrote his symphony. Frances Arnold played piano and guitar as a teenager and she is still very fond of music.

“When a good science team is working, it’s kind of like a good band” – James Allison in his Nobel Prize interview

Furthermore, the dynamics between the members of a music band can be compared with the team effort found within a research group. Medicine laureate James Allison points out this distinct similarity between music and science. According to Allison, it is necessary in both fields to build a team where each individual makes their own contribution to the overall work. However, it is important that the communication between the members work so smoothly that each individual also understands what needs to be done to accomplish breakthroughs. Each member is doing what they are supposed to. As James Allison states “every now and then my lab has been as well tuned – it feels like a really good band” – the concept of great team work leading to great success can be applied to both science and music.

“When I was twelve, my father gave me a Gibson C1 Classical Guitar, and taught me how to play for about a year. He was an amazingly good teacher, who never got impatient with my ineptitude. I wish I had his teaching skills. Although I went on to take more formal lessons (with Richard Pick, a well-known teacher at the time), I cherish the fact that my father was my first teacher and all the hours we spent playing duets together. I still play and get immense enjoyment from the guitar, though I do not have his skills. And I wish I had talked with him more about playing. My father suffered from dementia in the last years of his life, but continued to play guitar. On a visit home I gave him some guitar versions of the Bach cello suites, which he would play for hours a day. On a return visit, he told me that he thought this guy Bach was terrific. I realized that with his memory going, he was rediscovering Bach every day, which was the one consoling consequence of such a horrible condition.” – Martin Chalfie in his biography

Medicine laureate Barbara McClintock played the tenor banjo in a jazz band in New York during her senior year at Cornell University. However, as with many other scientists, McClintock discovered that her love for science was greater than her love for music so she decided to immerse herself completely in her research work. Nonetheless, she was very fond of music, enjoying its rhythm and structure.

Two other Nobel Prize awarded physicists Martin Chalfie and Frank Wilczek are keen musicians in their spare time. Chalfie’s dad taught him to play guitar from an early age, and Wilczek started playing piano, drums and accordion as a child. Similarly to Südhof, Wilzcek believes that music requires the disciplinary practice to acquire the basic patterns as well as the creativity to put these patterns together in novel ways. A reoccurring favourite amongst the scientists is the composer Bach. As Wilzcek summarises it: “Bach is a great manipulator of patterns”.

In Wilczek’s book ‘A Beautiful Question‘, he discusses if the world embodies beautiful ideas. He then mentions the idea of a ‘music of the spheres’. It is an ancient philosophical term used by classical astronomers and it represented the supposed ‘music’ produced by the movements of the celestial spheres or heavenly bodies. Maybe these spheres of music are accessible to Nobel Prize awarded scientists? That remains a mystery.

Photo credit: Albert Einstein, Photo found in the public domain. Max Planck, Library of Congress. Frances Arnold, Photographer: Clément Morin. James Allison, Video by Nobel Media. Martin Chalfie, Courtesy of Martin Chalfie.

First published March 2019