On the doors of the Northwestern University Technological Institute a poster of a smiling Fraser Stoddart greets visitors: ‘Home of Fraser Stoddart, recipient of the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry’. It’s the first days of the semester and the courtyard is crowded with new students.

“I talked to this brilliant young scientist, Matthew, earlier today and told him: ‘You are not going to get successful in life unless you break the rules’,” says Stoddart. “And he looked at me and said, ‘maybe you just bend them, Fraser?’ Oh no, I said, you’ve got to break them.”

© Nobel Media. Photo: Rasmus Lundgren

During his career, which spans more than six decades, Stoddart has broken rules and, on occasions, upset the research establishment. His journey started in 1942 outside Edinburgh, Scotland, where he spent his early school years also working at the family farm, feeding the animals and later mending farm machinery. This setting, he says, gave him the opportunity to get involved in engineering. “The first tractors and motorcars were so simple that you could take them apart. They had to be so in order to make them efficient again.”

“Since receiving the Nobel Prize, I have often been asked how to be awarded a Nobel Prize. I always tell them that everyone’s journey is different. I tell them my story about being brought up on a farm without electricity. That is not going to be repeated. These are stories of a particular time. It is going to be a different story next time, in a different country, and in a different society.”

The main building of Northwestern’s Technological Institute, dedicated in the early summer of 1942, is only three weeks younger than Stoddart, now one of its most famous occupants. From the main entrance it’s a fairly long walk through a maze of low ceiling corridors to what Stoddart calls the ‘RP’, short for ‘Research Palace’.

Stoddart arrived at Northwestern in the mid-2000s after a few years as a professor at the California Institute of Technology. Before Caltech he worked at the University of Sheffield and then, at the age of 49, became a professor at the University of Birmingham. Throughout his career, he has had to face constant competition in the world of academia.

“I think it happens to you in mid-career sometimes that you are just going to be overwhelmed and squashed thereunder if you don’t rise above the parapet and say what you think. Maybe I over-enjoyed it. I started to really enjoy it. And I kept on doing it.”

He continues, “People were so nasty in my early years – so competitive and so unpleasant to each other and to the students.”

Left to right: 2016 Chemistry Laureates Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Fraser Stoddart and Ben Feringa, and Medicine Laureate Yoshinori Ohsumi at the Nobel Prize award ceremony.

© Nobel Media. Photo: Pi Frisk

Stoddart received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2016 alongside two other chemists, Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Ben Feringa. Like many Nobel Laureates before them, the three received the award for discoveries that dated back to decades earlier. And in some ways Stoddart’s work can be traced back even earlier – to those early years at the family farm in Scotland. Except, instead of tractors and other farm machinery, his research deals with much smaller machines.

The researchers worked in the field of molecular machinery – aiming to create miniature machines out of molecules – but in the early 1980s the field had become stagnant. Then in 1983 a breakthrough came from France: Sauvage managed to link two ring-shaped molecules, thus forming a mechanical chain called a catenane. The research took off.

A few years later, in 1991, Stoddart’s research group threaded a ring – similar to that created by Sauvage’s team – to an axle and made it jump back and forth in controlled movements, much like a shuttle. The rotaxane, as the molecular formation is called, in turn laid the ground for Feringa’s 1999 discovery of the mechanisms for building molecular motors and later a nanocar, a tiny electrical car built up by just a couple of molecules, each sized about one-thousandth width of a strand of human hair.

Throughout the years working in overlapping fields, the three professors – Stoddart, Sauvage and Feringa – did not compete against one another, which is not always the case among scientists.

“It’s really a great story of friendship,” Stoddart says. “From our own vantage points we were very careful not to step on each other’s toes. This was such a new area of chemistry that the landscape was so open, there were so many places we could go, so much free space that we didn’t have to encroach on each other’s territory.” He adds, “That is very different from my first twenty years in academia.”

Sauvage and Stoddart first met at a conference in Italy in the spring of 1979 and then kept in touch. When Stoddart’s team published their research in the early 1990s, Sauvage was asked to review the manuscript. He even called Stoddart afterwards to congratulate him, Sauvage explains. “The relationship between us has been excellent and remarkably friendly. Our families met several times and our children know each other, especially Alison, Fraser and Norma’s youngest daughter, and Julien,” says Sauvage.

Chemistry Laureates Jean-Pierre Sauvage and Fraser Stoddart.

© Nobel Media. Photo: Alexander Mahmoud

In the corridor, two of Stoddart’s students, both from China, are chatting next to a water fountain while filling up their bottles. They exchange some words with Stoddart before going back into the lab. The door to Stoddart’s office is open. “I am rebelling against the hierarchical system that visited me during the early days of my career. I have had an open-door policy for my students for many decades so if a student wants to talk to me and he or she sees that my door is open, which it most times is, they can just come in,” says Stoddart.

This is where the current focus lays for Stoddart. He has largely left his research life behind and is now a mentor and a teacher to the constant flow of about thirty to forty students working in the lab. Most of them work on different topics. “They have very much free reign to do what I call new chemistry,” he says.

Over the years more than 300 undergraduate and graduate students have worked in his labs in the UK and US. Only a small portion currently working in the ‘RP’ are from the US or Europe. His students are predominantly from Asia. Minh Nguyen, from Vietnam, came to work in Stoddart’s lab in 2015, conducting research on mechanically interlocked molecules (MIM). “The doors to Fraser’s office are almost always open which means that you have many chances to talk or discuss with him,” says Nguyen. “I believe there is another meaning to his ‘open-door policy’: That opportunities should be open to everyone. When you have passion to do something that will help your career and you ask for help, you will get the support from Fraser.”

The news in the beginning of October 2016 that Stoddart together with Feringa and Sauvage had been awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was a much celebrated occasion for the young researchers at the ‘RP’. Stoddart himself was woken up a little after 4am by a call from Sweden giving him the news about the prize. He was alone at home – Stoddart’s wife Norma, who also was a close colleague, had passed away in 2004.

Norma Stoddart was diagnosed with cancer in 1992. It was the lack of promising treatments in the UK at that time that led to Fraser Stoddart taking a job at UCLA, therefore relocating the family to the US. “The story is of course that my wife was the top student in her years at Edinburgh. She was a very quick thinker and my two daughters followed in her footsteps and got top degrees.”

“I ended up being the dunce of the family in a sense,” he laughs. This didn’t stop Stoddart from becoming knighted by the Queen of England and earning the title of “Sir” before his name.

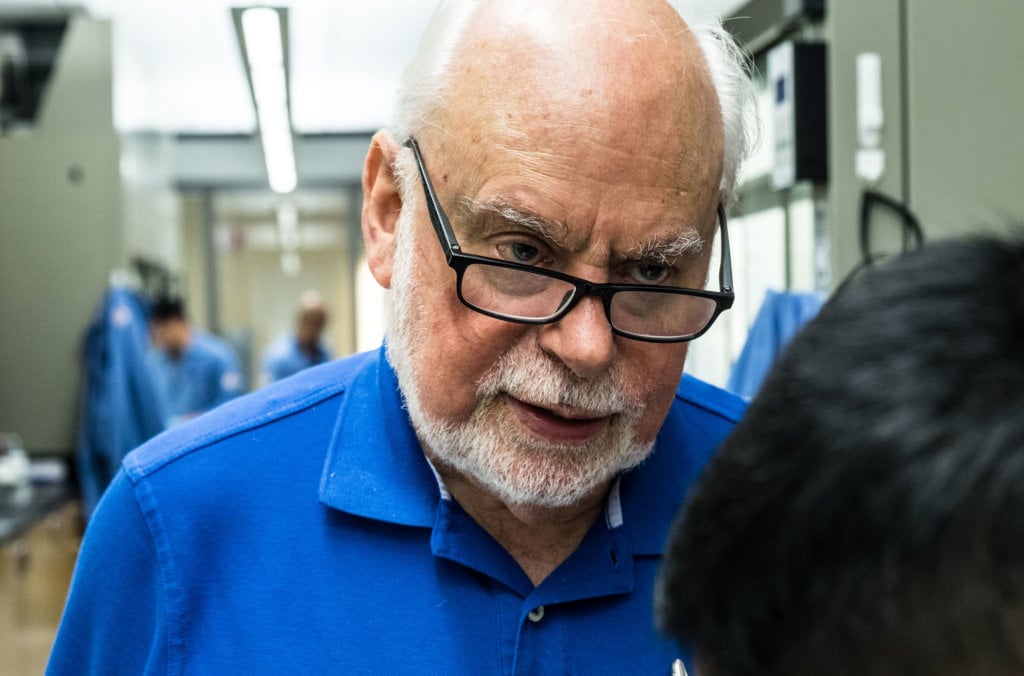

Fraser Stoddart speaks to members of his group.

© Nobel Media. Photo: Rasmus Lundgren

At the ‘RP’, Cristian Pezzato, a PhD student from Italy, works in front of a laptop at one of the desks. “We have a lot of freedom carrying out our own projects and that drives you to be more scientifically independent. I am also collaborating with people of different research backgrounds that come from all over the world. That has led me to learn different approaches and different point of views,” Pezzato explains.

Nguyen has similar thoughts about the ‘RP’: “The diversity among the students gives a comfortable feeling for a foreign researcher as myself. We are now possibly the most diverse research group with members from fifteen different countries. My colleagues and I often say, that after having experienced our group, one can work in any place on earth!”

For Stoddart, being awarded the Nobel Prize has come with a few changes: “I get my own parking space now with a lovely purple little board that says it’s reserved for me,” says Stoddard. His fellow laureate, Ben Feringa, on the other had was offered a bicycle space at his university in the Netherlands. Inspired by Feringa, Stoddart once asked the president of Northwestern University whether he can park a bicycle in the parking spot.

But Stoddart jests, “I don’t have a bike. And I am not sure I want to get back on one. Don’t tell anyone.” He continues, “I like to play these silly little games you know, particularly if you can twist the arms of university administrators. That has become easier after the Nobel Prize.”

By Rasmus Lundgren

First published October 2019