by Øyvind Tønnesson

Nobelprize.org Peace Editor, 1998-2000

1 December 1999

Stable socialist dominance, strong commitment to the western military alliance and support for the United Nations were central features of Norwegian politics after the Second World War. To what extent did these features similarly apply to the Nobel Committee? Who were the committee members, what political values did they represent, and how were these values expressed in their awarding policy?

The revival of the Nobel Peace Prize

When the Second World War ended in 1945, six years had already passed since the Nobel Peace Prize was last awarded. The members and deputy members of the Nobel Committee of the Norwegian Storting had not been assembled during the war. Some of them had remained in Norway; others had lived abroad – in Sweden, England or the United States. Since 1944, they were hoping that the committee would once more resume its activity. Nominations, however, had to be registered in time, i.e. before February 1, and the committee itself had to be legally appointed. Initiatives to generate valid nominations were thus taken both by members of the prewar committee as well as the Chairman and Deputy Chairman of the Nobel Foundation’s board in Stockholm.

The list of registered candidates was to be very short: The International Committee of the Red Cross and the Red Cross organizations in Sweden and Norway were nominated for their wartime humanitarian efforts. Another nominee was American Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, primarily for his role in the planning of a new world organization, the United Nations. On November 27, 1944, the day Hull resigned from his post as US Secretary of State, former Norwegian Foreign Minister, adviser and Nobel Committee member Halvdan Koht, sent a letter to the committee containing a list of nominees for the Peace Prize. In addition to Cordell Hull, the list included the names of the most prominent allied leaders: Winston Churchill, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Josef Stalin.1 From this list, only the name of Cordell Hull was duly registered and considered for the 1945 Prize. The explanation seems to be that Koht gave grounds only for Hull’s nomination.

An even more significant initiative to nominate candidates was taken by the President of the Storting, C. J. Hambro, and three other prominent Norwegians2 who had earlier been working for the Nobel Committee, at a meeting in the Norwegian Foreign Office in London on January 23, 1945. These men were all closely involved in the planning of a new Norwegian foreign policy after the war. They concluded that the Peace Prize should be awarded as soon as possible. Two of them wrote letters of nomination, naming the International Committee of the Red Cross and Cordell Hull, respectively. Hambro also received two letters nominating the same candidates from Philip Noel-Baker, British MP and Joint Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister of War Transport.

A nomination for the 1945 Nobel Peace Prize, written on a war ministry’s letterhead. Philip Noel-Baker’s nomination of Cordell Hull.

Why was it so important to award the Peace Prize in 1945? We do not know for sure. But this was probably viewed as the best way of reviving the Prize internationally – the Nobel Peace Prize should not vanish along with the international order of the interwar period. An early award – especially an award to the former US Secretary of State – could also be construed as politically opportune. One might hope that it would both generate American goodwill towards Norway and promote the establishment of the United Nations (UN) as an effective international institution, an important objective for the wartime Norwegian government-in-exile. C. J. Hambro was at that time also the Norwegian representative to the conferences where the establishment of the UN was being planned.

When the prewar Storting was reassembled early in the summer of 1945, Hambro made sure that one of the first items on the agenda was the appointment of new members of the Nobel Committee. In terms of party affiliation, the new appointments represented no change; three of the five were members of non-socialist parties, two were members of the Labour Party. The appointments, however, were criticised by some quarters in the Norwegian press. It was pointed out that the members and deputy members were all men, and that they were primarily leading representatives of their parties. When the committee finally convened on November 12, two prizes were at its disposal. Without much debate, the committee awarded the 1944 Prize to the International Committee of the Red Cross and the 1945 Prize to Cordell Hull.

Norwegian politics and the Cold War

It was a common judgment by most Norwegian politicians that the country’s prewar policy of neutrality had been a failure, and in 1945 those who had been responsible for that policy lost their influence. The government which had worked from London during the war resigned and an interim coalition government ruled until general elections were held in the autumn. The Labour Party won the majority of seats in the Storting and was to be the ruling party for an uninterrupted period of eighteen years. For some time, the Norwegian Communist Party represented a serious challenge to the socialists in the organized labour movement. On the opposite side of the political spectrum, the non-socialist opposition consisted of four different parties, representing different social interests and cultural values.

Until 1949, peace and security – and international affairs in general – were not among the most important topics in Norwegian political debates. It was generally agreed that Norway should follow a policy of “bridge-building” between the great powers, together with the other Nordic countries.

In 1948, however, Norway joined the Marshall Plan, and in 1949 the country became one of the founding members of NATO. The policy of bridge-building was abandoned and a great majority in the Storting favoured western alignment, although there were many critical voices – certainly in the Communist Party, but also among the socialists in the Labour Party. The Labour leadership campaigned intensively against the communists who quickly lost popular support and influence.

Norway, and Norwegians in general, had a highly positive attitude towards the United Nations and its global activities. Most Norwegian politicians were fundamentally opposed to colonialism and hoped that former colonies would peacefully become independent democratic nations. Norway favoured UN programs for economic and social development in poor countries, and as early as in 1952, the country engaged in a bilateral project to develop the fishing industry in Kerala, India. Norwegian development aid was to get relatively broad popular support and may indeed be seen as the product of two sorts of idealism: the labour movement’s ideal of international solidarity on the one hand, and christian charity on the other.

The Nobel Committee in a period of transition

In 1945, members of the Nobel Committee were all animated by a strong feeling of relief because the war was over. That feeling was probably stronger than the differences among them in terms of ideology and party affiliation. The awards in 1945 seem to have been made without much debate, although Committee Chairman, Gunnar Jahn, noted in his diary that he would have preferred not to award the Prize that year.

Differences in terms of political thought, however, were soon to exert a strong influence upon the committee’s work. There was strong disagreement in 1946, for instance, when three of the candidates namely, John Mott, Emily Greene Balch and Alexandra Kollontay, had strong individual supporters on the committee. Disagreement would not be unusual in the following twenty years.

When trying to analyse the work of the Norwegian Nobel Committee and the list of Peace Prize Laureates – from any period since the first award in 1901 – one should be careful not to exaggerate the importance of a single member’s beliefs or political values. The arguments from nominators count, and so do the reports from the committee’s professional advisers. In the end, however, the members would have to clarify their own positions and then try to reach consensus or make a vote. At this point, their personal convictions would certainly be of great importance.

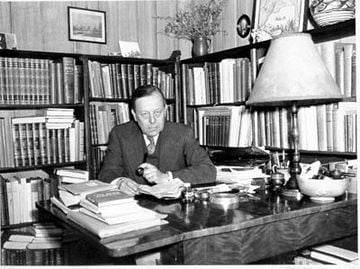

From the diary of Committee Chairman, Gunnar Jahn, it seems that he strongly wanted to prevent political opportunism from influencing committee decisions. Jahn had been Director of the Norwegian Central Bureau of Statistics since 1920. During the war, he was one of the leaders of the Norwegian resistance. In 1945, he was Finance Minister in the interim government and from 1946 to 1954, he was Managing Director of the Norwegian Central Bank. Married to feminist and peace activist Martha Larsen Jahn3, Gunnar Jahn was a liberal intellectual, a professional who was different from his fellow committee members. He had never been a member of the Storting; competing for popular support was not his line of activity.

|

| The Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee, Gunnar Jahn, in his home in 1946. Copyright © Scanpix |

During his period as Committee Chairman, Jahn tried to keep a balance between different categories of laureates. He wanted more awards to those who were working against armament and war. He also tried to keep the Nobel Peace Prize from becoming a non-controversial award for humanitarian relief work. Consequently, and on many occasions, he favoured candidates who were controversial in the western world.

In 1946, he alone supported the candidacy of Emily Greene Balch, who in his opinion, was “the only candidate who fulfilled the terms of Nobel’s testament”. The only socialist member present was Martin Tranmæl and he spoke for the Soviet diplomat, Alexandra Kollontay. But he was willing to vote for Balch as a second best candidate. The majority, consisting of two non-socialist deputy members and Birger Braadland of the Farmers’ Party, favoured the Christian candidate, YMCA President John Mott. Since both Jahn and Tranmæl were firmly against an award to Mott, the majority group decided to split the 1946 Prize in two: one for Mott, the other for Balch. The chairman refused to give the presentation speech for Mott, but in public he kept silent about the disagreement. Arbeiderbladet, the newspaper which Tranmæl himself edited, criticized the decision to award the Prize to the President of the YMCA and expressed regret that Kollontay was not selected.

Alexandra Kollontay was a leading communist long before the Russian revolution in 1917. During the First World War, she carried out communist anti-war propaganda in Norway and got to know people in the Norwegian labour movement. Later, she came back to Norway and Sweden as a Soviet diplomat.

Copyright © Scanpix

Alexandra Kollontay was nominated by the Finnish government and by the Swedish and Norwegian communists and socialists who also organized a campaign in her favour. Their argument was that she had been working actively for peace between Finland and the Soviet Union from 1940 onwards. They nominated Kollontay once more in 1947, but Tranmæl must have known that she would not be accepted by his fellow committee members. The two deputy members, Smitt-Ingebretsen and Oftedal, who had favoured John Mott in 1946, now favoured Mahatma Gandhi, but the three others were against it. (The question why Gandhi was not selected is discussed in a separate essay). In 1947, the Prize was awarded to The Quakers, a unanimous decision. The following year, the Prize was reserved. The Norwegian socialists’ support for Kollontay may, at least to some extent, be seen as an expression of their version of “bridge-building” between east and west. When that policy was abandoned in 1949, they would never again think of nominating a communist for the Peace Prize. Tranmæl himself became one of the most outspoken anti-communists in Norwegian public debate and in the internal discussions of the Nobel Committee.

Socialist take-over in 1948?

In the autumn of 1948, it was time for the Storting to appoint new members to the Nobel Committee. The Labour Party, referring to its majority position in the Storting, insisted that they should have three members in the committee. Observing the principle of proportional representation, they also voted for a communist, Kirsten Hansteen, as first deputy member. The two new Labour members of the committee were Gustav Natvig Pedersen, a left-winger, and Aase Lionæs, the first woman to become a member of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. The two remaining non-socialist members were Gunnar Jahn and C. J. Hambro. The non-socialist opposition strongly criticized the Labour Party for making the appointment of committee members a question of party membership, but only voted against the appointment of Kirsten Hansteen as first deputy member.

The new committee, with its socialist majority, remained without the replacement of permanent members until 1964. But did the socialist “take-over” actually matter? Were the prize awards to become expressions of a “socialist” interpretation of peace? In 1951, many non-socialist newspapers wrote that the award to the French labour leader Léon Jouhaux resulted from the socialist majority in the committee. They argued that although he should be recognized as a prominent organizer of the labour movement, the award was not consistent with the terms of Alfred Nobel’s will. In general, however, criticism against the Norwegian Nobel Committee’s awards in the 1950s and 1960s was not directly related to party politics. With the exception of the communist press, which considered most prize awards to be wrong, most critics who found the decisions of the committee controversial, did so for more than just purely ideological reasons. But why did the three socialists in the committee not leave a more visible red mark on the committee’s record?

|

| Comrades. When Léon Jouhaux, the French labour leader, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, some Norwegian conservatives thought it was due to the Labour majority in the Nobel Committee. Jouhaux (right) and committee member Tranmæl of the Labour Party at the prize award ceremony in 1951. Copyright © Scanpix |

One explanation seems to be that they never – possibly with exception in 1951 – acted as a strongly united faction within the committee. They let Gunnar Jahn keep the task of chairing it. He normally gave the presentation speeches at the prize award ceremonies, a very important task since the committee in those years did not present any common motivation when announcing the Prize. The three socialist members did not have a uniform understanding of world affairs either. Consequently, one or two of them would share the views of either the liberal Gunnar Jahn or the conservative C. J. Hambro.

The most important reason, however, was probably the development in international relations. The international organized peace movement was split between pro-Soviet communist movements on one hand, and non-communist peace organizations who could only operate in the west on the other. The Cold War increasingly came to embrace the whole world and there was little room for independent peace initiatives with a realistic chance in bringing about détente, not to mention disarmament or lasting peace. In this context, all the members of the Nobel Committee, like many other Norwegians, hoped that the United Nations (UN) would be able to prevent armed conflicts from breaking out or escalating into another world war. Prize awards to UN institutions or to politicians involved in UN affairs were generally acceptable to all the members of the Nobel Committee, regardless of their political affiliation, and they were welcomed in most western countries. From 1945 until 1966, seven prize awards out of eighteen were – directly or indirectly – related to the development of the United Nations.4

In a speech in early 1959, Aase Lionæs, committee member and later chairwoman, said that “the socialist understanding of peace work has won through in the Nobel Committee”. Peace work, she said, is the struggle against poverty, ignorance, disease and homelessness in the world. Was she right? Had this understanding of peace work become the foundation of the Nobel Committee’s prize-awarding policy? It would seem so, at least to some extent. The Laureate of 1958, Father Dominique Pire, was awarded the Peace Prize for his efforts to help refugees, the 1954 Prize had been awarded to the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, the award to Albert Schweitzer (1952) was for his work as a missionary surgeon in Africa, and John Boyd Orr was awarded the 1949 Prize primarily for his role in establishing the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) of the UN. But was it fair to ascribe the understanding of peace work to socialism which Lionæs presented?

Non-decisions, compromises and controversies

Between 1945 and 1966, many of the prizes resulted from compromises. It was reserved eight times during the same period. On some occasions, committee members seemed to have considered no candidate to be worthy of the Nobel Prize. On other occasions, each member had his or her personal favourite. The committee clearly made a compromise in 1953, when George Marshall was awarded that year’s Prize and Albert Schweitzer was awarded the Prize for 1952. That was also the case in 1963, when the 1963 Prize was shared between the International Committee of the Red Cross and the League of Red Cross Societies and the 1962 Prize was awarded to the American anti-nuclear weapons activist Linus Pauling.

During this time, members of the organized peace movement were critical about the awarding policy of the Norwegian Nobel Committee. For a long time they considered it to be especially negative that the Peace Prize was not utilized to support those who were fighting against nuclear weapons, the most horrible threat to humanity. Indeed, some Laureates were engaged in efforts opposing the nuclear arms race. Having received the Nobel Peace Prize, Albert Schweitzer was spurred to participate in mobilizing public opinion against nuclear testing. In 1957, his “Declaration of Conscience” was broadcast from Oslo and transmitted by 140 radio stations to most of the world. Philip Noel-Baker spoke for comprehensive agreements on disarmament when he was awarded the Peace Prize in 1959.

Despite these developments, activists like the American journalist Norman Cousins and the Nobel Prize Laureates Bertrand Russell (literature) and Linus Pauling (chemistry) were unsuccessfully nominated again and again. When the latter was finally awarded the 1962 Peace Prize, the United States and the Soviet Union had already signed the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which put a stop to the dangerous atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons. The peace movement welcomed the Pauling award, but the decision was still one of the most controversial in the whole period of Gunnar Jahn’s chairmanship. Morgenbladet, a strongly conservative and pro-American Norwegian daily newspaper, described it as “a slap in the face”.

In the period 1945-1966, most of the prize awards were rather uncontroversial in Norway. It was at this time that a new category of peace work, the struggle for human rights, was awarded with a Peace Prize. When Zulu Chief Albert John Lutuli was awarded the 1960 Prize for his non-violent struggle against the South-African apartheid policy, the decision was unanimous. The same was true when Martin Luther King, Jr. was awarded the Prize for 1964. In Norway, there were few critical voices although in South Africa, the US, and many other western countries, it was considered highly controversial to award the Nobel Peace Prize to such “troublemakers”.

A Norwegian voice

There are few signs, if any, that the Norwegian Nobel Committee was directly influenced by the Norwegian Foreign Office in the period 1945-1966. There was no need. Most Norwegians shared the same general foreign policy values and those who did not, were usually not appointed to the committee. The general avoidance of candidates who were controversial in the Cold War context, the wish to promote the development of the United Nations, and the willingness to include the struggle for human rights into the interpretation of peace work, were all compatible with official Norwegian policy. All these represented lines of thought within the Nobel Committee.

1. The following is an extract from Halvdan Koht’s letter to the Nobel Committee, datelined Washington D. C. , November 27, 1944: “In 1945, it will be hopefully possible for the Committee to resume its activity and award the Peace Prize. Since nominations, according to the statutes, must be registered before February 1. I hereby suggest the names of some men who should be considered as candidates for the prize. (…) The candidates that I wish to mention are the following:

a) Cordell Hull, American Secretary of State from March 1933 until today, November 27, 1944. I believe the Nobel Committee earlier have gotten a report on his efforts to break down the

international customs barriers. In the endeavors to create a lasting peace after this war, his name is primarily associated with the Moscow-agreements of October 1943. Moreover, there are available statements from him on his peace program from July 23, 1924, March 21 and April 9, 1944. When Roosevelt accepted Hull’s resignation, he called him the ‘Father of the United Nations’.

b) President Franklin D. Roosevelt

c) Prime Minister Winston L. Churchill

d) Foreign Minister Anthony Eden

e) Premier Josef Stalin

f) Former Commisar for Foreign Affairs, Maxim Litvinov

g) President Eduard Benes

h) The South African statesman Jan Smuts”

2. The three men were professor Frede Castberg, professor Wilhelm Keilhau and Arne Ording.

3. Martha Larsen Jahn was older than her husband. She had been an active member of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom since its formation in 1915. It does not seem unreasonable to assume that she had some influence on the thinking of Gunnar Jahn.

4. The Laureates were: Cordell Hull (1945), John Boyd Orr (1949), Ralph Bunche (1950), The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (1954), Lester Bowles Pearson (1957), Dag Hammarskjöld (1961), UNICEF (1965).