by Øivind Stenersen*

From the very beginning the Norwegian Nobel Committee chose to define humanitarian efforts as an essential part of promoting “fraternity among nations”. In awarding half of the 1901 Peace Prize to the founder of the Red Cross, Henri Dunant, the committee focused on a basic aspect of the word “humanitarian”: helping victims of war was classified as crucial in order to improve the lives of mankind and reduce suffering. Ignoring the criticism from influential people in the International Peace Movement like Bertha von Suttner, the Nobel Committee continued to honour the legacy of Dunant by honouring the International Red Cross three times: in 1917, 1944 and 1963.1 In 1963 the ICRC shared the prize with another branch of the Red Cross family, the League of Red Cross Societies.

From 1901 till 2003 the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to 111 laureates. Among them were six men, one woman and eight different organisations that belonged to the humanitarian category. Additionally, the prize to the 1946 Laureate, the president of the World Alliance of Young Men’s Christian Associations (YMCA), John R. Mott, was partly motivated by humanitarian arguments. The YMCA brought relief to millions of prisoners of war during the first and second world wars.

Assistance for victims of war

Assisting prisoners of war was among the main tasks of the Norwegian polar explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen, the Nobel Peace Laureate of 1922.2 Nansen organised relief work during the 1921 famine in the Soviet Union, and the following year he was appointed as the first High Commissioner for Refugees by the League of Nations, a position in which he used most of his energy on resettling Greeks and Turks after the Greco-Turkish War. From 1925 Nansen worked to secure homes for Turkish Armenians inside the Soviet Union.

His work was carried on by the Nansen International Office for Refugees, an institution founded in 1930 by the League of Nations and rewarded with the Nobel Peace Prize of 1938.

The Norwegian Foreign Minister Halvdan Koht was an influential nominator of the Nansen Office in 1936. He hoped that a Peace Prize could help prevent the dismantling of its activities, as proposed by the Soviet Union. The Bolshevik government wanted to see the end of League of Nations’ aid to Russian refugees, particularly because many of them were taking part in anti-Soviet activities.3 At the same time, the Nobel Committee hoped that the 1938 prize would strengthen the shattered image of the League of Nations. In a time of crisis, many people had lost faith in the organisation because of its inability to prevent war and create peace. Therefore it was necessary to focus on the humanitarian work accomplished by the Office.

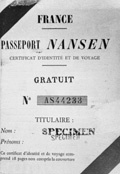

During its first years, the Nansen Office focused its aid effort on a people for whom Nansen had had particular concern: the Armenians. The Nansen Office organised the construction of villages to house more than 40,000 Armenians in Syria and Lebanon and resettled another 10,000 in Erivan in the Soviet Union. In the middle of the 1930s it handled refugee cases mostly from France, Syria, Yugoslavia, Greece, Germany and Bulgaria. Others were from Czechoslovakia, Turkey, Romania, Switzerland and China. A wide range of relief measures were implemented: office representatives issued documents of identification for stateless refugees (“Nansen passports”), arranged visas and appealed expulsions. They also handled tax-issues, procured housing and employment, gave loans to tradesmen, traced missing persons and helped supply food and medicine to the sick and the elderly. In 1933, the organisation was a driving force in hammering out the Refugee Convention of the League of Nations. Governments that signed were obliged not to expel refugees as long as they did not represent a threat to national security or to the general public order.

A proof-print of the “Nansen Passport” published in France.

To the satisfaction of the Nobel Committee, the tasks of the Nansen Office were carried on by a new agency, the Office of the High Commission for Refugees under the Protection of the League. It opened in 1939 with headquarters in London.

In 1955, the reserved Peace Prize from 1954 was awarded to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The UNHCR was established by the UN General Assembly in 1950 and made responsible for ensuring that all refugees receive international protection in accordance with the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees adopted in 1951. According to this convention, a refugee was defined as an individual forced to leave his or her home country for fear of persecution on racial, religious, political or nationality grounds or for belonging to a particular group in society. All signatory states were committed to issuing identity documents to refugees and to not return people who were in danger of undue suffering in their home country. It also determined that refugees were to be guaranteed international protection under law and granted fundamental rights in the host country.

In the first half of the 1950s, the UNHCR sought solutions to the refugee problem by means of voluntary repatriation, emigration or integration in the country of asylum. Particular attention was focused on the plight of refugees within Europe. In 1955, European refugees comprised nearly half of the 2.2 million people under the protection of the UNHCR. Of these, some 70,000 were living in approximately 200 camps in West Germany, Austria, Italy and Greece. Large refugee groups were also found in Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Iran.

When the UNHCR was founded, it was decided that the UN would cover its administrative expenses, but that specific measures in the field would have to be financed and carried out by governments or governmental and non-governmental organisations. It soon became clear that it would be difficult to procure sufficient funding from the member countries by voluntary means, and in 1955 the organisation was faced with a financial crisis. In awarding the Peace Prize to the UNHCR, the Nobel Committee sought to bring the problem of refugees into the international limelight and thus promote an increase in the volume of voluntary financial support to the organisation.

When the Nobel Committee awarded the prize to the UNHCR for the second time, in 1981, the refugee problem remained unsolved and had grown even larger. In the early 1980s, the problem was largely confined to the Third World, particularly the countries of Africa. The dramatic situation of the Vietnamese boat refugees was also the focus of international attention during this period.

The decision to use the prize money to set up a separate fund for disabled refugees was met with favour. It provided an opportunity for the High Commissioner to mark the year 1981 as the International Year of Disabled Persons, and was also a result of UNHCR’s desire to strike a blow for the most vulnerable of refugees: individuals suffering from physical and psychological trauma following acts of war; the mentally ill, the elderly and the sick.

Christian humanitarians

When the Nobel Committee turned down the candidacy of Mahatma Gandhi in 1947, it chose two other candidates closely linked to the development of pacifism and humanitarianism: The British Friends Service Council and the American Friends Service Committee, both aid organisations set up by the Christian society the Quakers.

In accordance with the conviction that the will of God could be revealed in silent contemplation by every human being, the Quakers developed a special kind of Christian pacifism. Quaker pacifism meant that “the Light of Christ” should be transformed into positive action by individuals, families, social groups, races and nations; thus creating an atmosphere of peace that would make wars impossible. In the 1760s William Penn tried to realize this policy of good deeds in the colony of Pennsylvania in North America, setting an example for a disarmed state.

The Quakers were not only pioneers in their call for European political unity and ecumenical cooperation between Christians. They also took up an early engagement fight against intolerance and social injustice which were looked upon as major roots of war; an attitude which explains the broad and industrious Quaker engagement for social and political reforms. In order to establish peace among nations it was necessary to create social harmony within the borders of every nation. Quakers were pioneers in the field of education and played an active role in reforming prisons and mental institutions. They were also in the frontline in the struggle against slavery and in the fight for women’s rights. In the early nineteenth century they helped found the first peace societies, and after that Quakers were instrumental in the development of the modern peace movement.

During the Second World War, the Friends launched a humanitarian operation much like that seen during the previous Great War. In Britain they introduced welfare initiatives in bomb-stricken areas, such as food supplies, equipment and personnel for bomb shelters, and assisted civilians fleeing the cities. In the United States the Quakers were particularly concerned about the plight of Japanese-Americans, who were sent to internment camps from 1941. The Friends ambulance service was again successfully deployed with a number of frontline divisions.

When the war ended in 1945, the Quakers were quick to take part in the reconstruction process. Large quantities of clothing and food supplies were shipped to the Continent, and vulnerable groups – concentration camp prisoners, slave labourers and scores of German refugees from Eastern Europe – were at the centre of attention. The Quakers set up schools in the refugee camps, distributed food and opened summer camps and “democratic” youth clubs. Apart from Germany, relief work was carried out in France, Austria and Greece, but it also reached the burnt-out regions of Northern Norway.

During the award ceremony in 1947 an American Quaker described their contribution in the following way: “This international service is not mere humanitarianism; it is not merely mopping up, cleaning up the world after war. It is aimed at creating peace by setting an example of a different way of international service. So our foreign relief is a means of rehabilitation and it is intended not merely to help the body but to help the spirit and to give men hope that there can be a peaceful world.” The chairman of the Nobel Committee agreed by citing some lines of a Norwegian poem: “The unarmed only can draw on sources eternal. The spirit alone gives victory.”

A White House vigil/civil disobedience by American Friends Service Council (AFSC) members.

Already as a student, the theologian, distinguished organist and doctor of medicine Albert Schweitzer decided to dedicate his life to humanitarian work. In 1904 the young Alsatian came across an article calling for qualified people for the French Missionary Company in the Congo. Schweitzer followed the appeal and started planning the building of a hospital in Africa. Through concerts and donations, he obtained sufficient funds to set off – accompanied by his wife – for the village of Lambaréné on the Ogowo River in French Equatorial Africa in 1913. Concentrating on developing bonds of trust between the hospital and the local population, he treated thousands of people suffering from severe illnesses like malaria, sleeping sickness, skin sores, leprosy, dysentery, venereal diseases, hernia and heart failure. Apart from occasional fund-raising visits to Europe, he continued his medical work in Africa for the rest of his life.

When Schweitzer received the reserved Peace Prize for 1952, the Nobel Committee especially appreciated his cultural philosophy, “Reverence for Life”, which served as an ethical principle for his humanitarian efforts. In his view the individual must constantly look beyond all that knowledge and science have created and penetrate to the elementary: The free human being seeks the joy of being allowed to care for life and avert suffering and destruction.

In the 1950s, many looked upon Schweitzer as a kind of earthly saint, and he received a unique welcome when he held his Nobel Lecture in 1954. More than 20,000 torchbearers greeted him in front of the Oslo City Hall, and a spontaneous fundraiser during his visit resulted in almost twice the amount of the Peace Prize.

Later critics have characterized him as a remnant of European cultural paternalism. Some have even suggested that Lambaréné offered Schweitzer an escape from the serious social and political problems of Europe; but in a fifty years’ perspective, such criticism seems out of proportion. In 1957, Schweitzer broke his silence and issued a statement against nuclear testing. His public appeal was broadcast in different languages from Oslo in cooperation with the chairman of the Nobel Committee.

In 1958, the Belgian Dominican priest Georges Pire received the Peace Prize primarily for his humanitarian work on behalf of European refugees. He organised a network of sponsors who sent parcels, letters of encouragement, clothing, food and medicine to refugees living in camps, and established a donation-based aid organisation that built homes for elderly refugees. Pire also utilised private donations to build several “European Villages”, each a miniature community consisting of small buildings with room for about 100 refugees. These villages were designed to give the refugees a chance to gain economic independence, and residents paid half of the rent.

A driving force behind Pire’s activities was his desire to serve the vision of European unity through humanitarian efforts. Several people in the European Movement supported his Peace Prize nomination as did the Norwegian ambassador in Brussels. Father Pire’s work was, however, never Eurocentric. In 1957, he and his closest associates created the organisation “L’Europe du Coeur au Service du Monde”, whose task it was to organise relief efforts in other parts of the world. The Nobel Committee found that Pire appealed “to all that is best in the Western European” and highlighted his desire “to erect a bridge of light and love high above the waves of colonialism, anti-colonialism and racial strife”. Such visions were clearly in line with the idea of fraternity as expressed in Alfred Nobel’s will.

In the 1960s, Pire concentrated his activities more and more on global efforts. He spearheaded the creation of a Belgian peace university, which organised summer courses for “fraternal dialogue” between peoples of different cultural backgrounds and continents. Pire also initiated development programmes in Pakistan and India. The projects, called “Islands of Peace”, promoted local cooperation between villages to improve the health and nutrition conditions with the aid of western expertise.4

Like John D. Mott and Georges Pire, the Laureate of 1979 Mother Teresa, said she was called by God to engage in Christian charity. The Roman Catholic nun of Albanian descent devoted her life to working among “the poorest of the poorest” in the slums of Calcutta. In 1950, she received permission from the Vatican to found an order, the “Missionaries of Charity”. By 1979, the order comprised 1,400 sisters and brothers in India, who ran 30 homes for orphaned newborns, 70 leper colonies and a number of homes for the terminally ill. In addition, the order had spread to and was carrying out relief work in Peru, USA (New York), Tanzania, Ethiopia, Israel and Yemen.

Mother Teresa was, however, viewed with scepticism in certain circles. Her tireless battle against divorce, birth control and abortion made her a conservative defender of the values promoted by the Vatican. Her organisation was blamed for spending millions on convents instead of building hospitals and for the fact that the homes for the dying lacked adequate medical equipment. At the same time, mother Teresa herself received the best treatment for heart problems in a clinic in the United States.

But such negative reactions had little effect on the popular support for “the Saint of the Gutter”. She was met with enthusiasm and a “People’s Peace Prize” when she came to Norway in 1979, requesting that the customary Nobel banquet should be called off. The Nobel Committee accepted the wish and gave her a cheque to “feed those who really needed a decent meal.”

After Mother Teresa’s death, strong forces inside the Catholic Church started the process of making her a saint. In 2002 the Pope signed a decree accepting as authentic a miracle attributed to the nun, and the next year the ceremony of beatification, which is one step short of canonisation, took place in Rome.

Food supply and children’s welfare

In the 1930s, the British nutritionist John Boyd Orr became deeply involved in efforts to improve living conditions for the people of Britain, playing a key role in the government-appointed national committee on nutrition. He went on to become one of the founding fathers, and thereafter the first director-general of, the United Nations Food and Agriculture organisation (FAO), established in November 1945 as the first specialised agency of the United Nations. It was his outstanding performance in these positions that made him worthy of the 1949 Nobel Peace Prize.

Boyd Orr focused his efforts on solving the post-war food crisis, which he considered to be the most immediate problem facing FAO. He set up the International Emergency Food Council, which, according to Boyd Orr himself, saved “millions of lives from death and starvation” in the three years it existed. Boyd Orr further proposed the establishment of a World Food Board, which would be equipped with executive powers to stabilize food prices on the global market. However, his proposal did not receive the support of the United States and the United Kingdom, and an agency with less authority, the World Food Council, was established instead. In response, Boyd Orr resigned as director-general of FAO.

In Morocco, 1954, FAO uses poison bait to combat locust invasion.

Boyd Orr saw his work for better nutrition in a wider context, which was highly appreciated by the Nobel Committee. In 1945 he served as president for the National Peace Council, whose membership comprised 50 British peace organisations. In addition, he was deeply committed to the movement to institute world government: The World Federalist Association.

In 1965, the Peace Prize went to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), which was founded by the UN General Assembly in 1946. The chief architects behind the organisation were former United States president Herbert Hoover, the last United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) president, Fiorello la Guardia and the Polish diplomat Ludwik Rajchman. Up to the early 1950s, UNICEF focused mostly on providing food, clothing and medicine to children and mothers in war-ravaged Europe, China and Palestine.

In 1953, the UN General Assembly decided to set up UNICEF as its permanent child-aid organisation, with long-term objectives aimed at work in the developing countries. The organisation gave priority to three main areas. The first was to implement programs for maternal and child health care. The second was to educate people about nutrition and to distribute protein-rich foods. The third was to combat diseases that destroyed the health or claimed the lives of millions of children each year. As part of these efforts, UNICEF built thousands of health clinics throughout the Third World.

The 1959, UN Declaration of the Rights of the Child served to strengthen the basis for UNICEF’s activities. The declaration stated that all children have the right to security, adequate nutrition, housing, education and protection against “all forms of neglect, cruelty and exploitation”. In the 1960s, UNICEF began to give priority to educational programmes, in close cooperation with other UN organisations.

Seated with other girls in an outdoor class of grade one students, two girls share a textbook, in a non-formal girls’ school in Jalalabad, capital of the eastern province of Nangarhar in Afghanistan.

The Nobel Committee described UNICEF as “an international device capable of tackling the giant task of liberating the children of the developing countries – who are all of them our joint responsibility – from ignorance, disease, malnutrition, and starvation”. In the view of the committee, these efforts represented “a great step forward in the idea of international cooperation”.

In 1970, the question of “bread and peace” was put on the Nobel peace agenda once again when the American scientist, Norman Borlaug, won the Peace Prize. The Iowa-born expert in genetics is known as the man behind the “Green Revolution” of the 1960s, which brought about vastly increased grain yields, first in Mexico, then in India and Pakistan.

The Nobel Committee related Borlaug’s achievement to the basic human right of freedom from starvation as recognised by the Charter of the United Nations and declared that his work had helped to turn pessimism into optimism in the dramatic race between population explosion and food production. By exploiting the new technology in agriculture, other branches of the economies in the developing countries could be modernised in the same way as the western European societies during the Industrial Revolution.

In his Nobel Lecture, Borlaug underlined that adequate food is the moral right of all mankind and that peace can’t be built on empty stomachs. The increase in grain production was only a temporary success in the war against hunger because the frightening power of human reproduction could ruin all progress. At the same time he criticised both rich and poor countries that used vast sums on arms instead of on research and education designed to sustain and humanize life. Unless the hungry half of the world population was secured employment, comfortable housing, good clothing and effective medical care, man might degenerate sooner from environmental diseases than from hunger.

Still the laureate was optimistic about the future since man is a rational being: By 1990 he hoped that man would have recognised the self-destructive course of irresponsible population growth and adjusted the growth rate to levels which would permit a decent standard of living for all mankind.

History has proved that Borlaug’s optimism was too strong. Thirty years after his Nobel Lecture, he repeated his warning from 1970 that unless the frightening power of human reproduction was curbed, the success of the Green Revolution would only be ephemeral. But again solutions were available: At the turn of the century the world had the technology to feed on a sustainable basis a population of 10 billion people. The more pertinent question was whether farmers would be permitted to use the high–yielding crop production methods as well as the last biotechnological breakthroughs.5

Medical aid and human rights

In 1999, the final Peace Prize of the 20th century was awarded to the independent emergency relief organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) which was founded as a result of experiences made by a group of French doctors during the Biafra conflict in the late 1960s.

In their service they had found it difficult to remain silent and neutral in the civil war as required by Red Cross statutes. Among them was the physician Bernhard Kouchner. In 1970, he started a new and flexible organisation whose aid workers could enter a conflict area illegally if necessary in order to help all victims and at the same time tell the world about violations of human rights.

In recognising MSF the Nobel Committee highlighted the willingness to send volunteers quickly to scenes of disaster, regardless of the political situation, and it praised the group for drawing the world’s attention to the causes of catastrophes, which could help to engage public opinion against oppressive regimes.

In the 1970s, MSF was dominated by French personnel and engaged in relief operations in Nicaragua, Vietnam, Lebanon and Turkey. After an internal dispute in 1979 about the rescue of Vietnamese boat people adrift in the China Sea, Kouchner broke out and the organisation was consolidated. In the next decade local branches were opened in new countries and French doctors were outnumbered by volunteers from other nations. A successful fund raiser in 1982 and financial support from the UN, the European Union and some governments secured MSF a more stable income.

In 1985, the organisation was banned from Ethiopia for saying the government had diverted aid and forced migration. Ten years later, MSF was among the first to call the massacre in Rwanda genocide, and it withdrew from refugee camps in Zaire and Tanzania controlled by Hutu leaders responsible for serious violations. In 1999, the chairman of the Nobel Committee drew special attention to the group’s commitment to Africa, because the misery there often fades from public consciousness.

At the end of the 1990s, MSF sent out 2,500 physicians and relief workers to areas stricken by conflict or disaster. In addition, the organisation had 15,000 local personnel in more than 80 countries, conducted a total of 6 million consultations annually and performed 200,000 surgical operations.

Mothers and their children awaiting assistance from MSF personnel in Niger.

But still some aid agencies scorned MSF for its intimate relationship with the news media and its sometimes glamorous images of attractive young doctors in action. Such analyses were categorically dismissed by the organisation, and its founder Bernard Kouchner insisted that speaking out about atrocities would help prevent them. “It is very important that MSF does not offer shelter for disgraceful acts and suffering. We need to convince people that the suffering of one man was the responsibility of all men. This work is not done, far from it.”

The same attitude was clearly demonstrated during the award ceremony in December 1999 when MSF members wore t-shirts with slogans against the Russian warfare in Chechnya. Such action was unprecedented in the history of the Nobel Peace Prize.

Humanitarian efforts and peace-building

Finally, let us sum up some of the main arguments used by the Nobel Committee to motivate the humanitarian prizes. Repeatedly, it has chosen human symbols, people who through their good deeds can serve as examples for contemporary and future generations. According to the Committee, these “champions of brotherly love” or “self-sacrificing” men and women served the cause of peace by holding out a helping hand to victims of armed conflicts, like prisoners of war and refugees.

The wish to heal the wounds of war was in itself an important factor in the deliberations. The Committee strongly believed that bitterness and calls for revenge could be reduced by humanitarian aid. It also favoured people and organisations striving for the principle that humanitarian rights should be codified by international conventions. This meant a steady support to aid organisations of the United Nations and a growing challenge to the principle of non-intervention.

The goal of narrowing the gap between rich and poor nations and the wish to strengthen human rights in the developing countries were other leading principles for the Nobel Committee. In this regard scientists and organisations dedicated to the task of tackling and overcoming economic and social privation were particularly relevant. Again and again the Committee stressed that we all have a global responsibility and that the proud tradition of humanitarianism must be put on the agenda of world politics.

Bibliography

Nobel Lectures: Peace 1901-1970.

Nobel Lectures: Peace 1971-1980. Tore Frängsmyr and Irwin Abrams, ed. Singapore, New Jersey, London, Hong Kong. World Scientific, 1997.

Nobel Lectures: Peace 1981-1990. Tore Frängsmyr and Irwin Abrams, ed. Singapore, New Jersey, London, Hong Kong. World Scientific, 1997.

Abrams, Irwin. Reflections on the First Century of the Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Institute Series Vol. 1, No. 5, Oslo, 2000.

Stenersen, Øivind. The Nobel Peace Prize. Some Aspects of the Decision-making Process, 1932-39. The Norwegian Nobel Institute Series Vol. 1, No. 4, Oslo, 2000.

Stenersen, Øivind, Ivar Libæk and Asle Sveen. The Nobel Peace Prize: One Hundred Years for Peace. Laureates 1901-2000. Oslo: Cappelen, 2001.

* Øivind Stenersen (1946-) obtained his cand. philol. in History at the University of Oslo in 1972. He has more than twenty years of experience as teacher in senior secondary schools and has taught and acted as examiner at universities and colleges. Since 1983, he has written textbooks in history for primary and secondary school levels. Stenersen is also co-author of the books The History of Norway from the Ice Age to Today and The Nobel Peace Prize. One Hundred Years for Peace. From 1999-2001 he was Nobel Institute Fellow and is currently working as Project Advisor at The Nobel Peace Center in Oslo.

1. See Ivar Libæk: Red Cross: Three-Time Recipient of the Peace Prize.

2. See Asle Sveen: Fridtjof Nansen: Scientist and Humanitarian.

3. Øivind Stenersen: The Nobel Peace Prize. Some Aspects of the Decision-making Process, 1932-39. The Norwegian Nobel Institute Series. Vol. 1, No. 4. Oslo 2000: 30.

4. See http://www.ilesdepaix.org/ and http://www.universitedepaix.org

5. See Norman Borlaug: The Green Revolution Revisited and the Road Ahead.

First published 26 February 2004